◎ To rookie and veteran observers, the fate of Wang Qishan is perhaps one of the more perplexing developments in recent CCP politics.

By Don Tse and Larry Ong

Introduction

To rookie and veteran observers, the fate of Wang Qishan is perhaps one of the more perplexing developments in recent Chinese Communist Party (CCP) politics.

Before the 19th Party Congress, pundits wondered whether Wang would retain his spot in the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee. Both Chinese and Western media carried conflicting insider information about Xi Jinping’s decision to keep Wang in a senior position. Wang ultimately vacated his Politburo Standing Committee seat and wasn’t named to the new CCP Central Committee at the 19th Congress. In their 19th Congress reshuffle postmortem, many scholars noted that Wang’s exit from elite politics was due to Xi adhering to Party retirement norms and leadership renewal procedures.

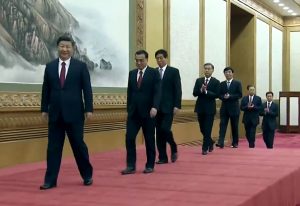

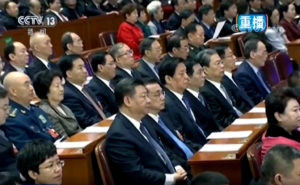

But Wang Qishan was not yet being put to pasture. The first rumors of Wang becoming China’s next vice president and tasked with Sino-U.S. relations surfaced in November. In December, news emerged that Wang was attending Politburo Standing Committee meeting as a nonvoting member. The following month, Wang punched his ticket to the Two Sessions meeting in March as a Hunan legislature delegate to the National People’s Congress. At the Two Sessions, our October 2017 forecast of Wang Qishan’s political fate was verified when his seating arrangement at the March 4 National People’s Congress preparatory meeting indicated that he was an unofficial “eighth” member of the Politburo Standing Committee, and later on March 17 when he officially replaced Li Yuanchao as vice president.

SinoInsider correctly predicted Wang’s political “comeback” before the rumors and speculation of his return because we understand the core issue driving elite Chinese politics today. This article will unpack what went into our analysis, and provide a concise overview of CCP factional fighting (neidou) and its role in shaping political developments in the People’s Republic of China.

Why Wang Qishan Stepped Down at the 19th Congress

In forecasting the 19th Congress reshuffle, we noted that Xi Jinping would have two priorities:

1) Fully consolidate power while resisting interference by Party elders and the collective leadership system.

2) Keep close ally Wang Qishan in office to preserve the results of the anti-corruption campaign and maintain its momentum for the next five years.

We deduced Xi’s priorities from the outcome of the 18th Congress, a major turning point in elite CCP politics, and through observing Xi’s policies in his first term. A detailed examination of the 18th Congress outcome and Xi’s first term policies is deserving of a longer treatise (or several book chapters). But a gist of what transpired is necessary to contextualize the 19th Congress results and Wang Qishan’s return to prominence.

For about two decades (1997 to 2012), the Jiang Zemin faction dominated the Chinese regime. Hu Jintao, Jiang’s successor, spent most of his reign as a puppet. Many observers noted that Hu’s orders often never passed the gates of Zhongnanhai. In 2012, however, a scandal involving top Jiang lieutenant Bo Xilai gave the Hu camp and incoming CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping an opening to seriously challenge the Jiang faction for control over the Chinese regime. Xi obtained permission from Party elders to prosecute Bo and his accomplices, and carry out an anti-corruption campaign. He also secured the services of top ally Wang Qishan in a downsized Politburo Standing Committee. But the deck was still stacked against Xi: Jiang faction members controlled the propaganda organs and the domestic security and legal apparatus, as well as the military; many Chinese officials continued to support the Jiang faction out of personal benefit and mutual interests; and Xi had no faction and few trusted officials to rely on. So Xi spent most of his first term consolidating power through an anti-corruption campaign, implementing sweeping military reforms, and slowly promoting old colleagues to senior positions to replace purged or retiring officials associated with the Jiang faction. By the 19th Congress, Xi had “crushing momentum” in the factional struggle.

Xi Jinping may had (and continues to have) momentum over his rivals, but factional fighting is a convoluted, counterintuitive, and consequential affair with few guaranteed outcomes. We came up with five 19th Congress scenarios and what we believed to be Xi’s two priorities. The extent to which Xi accomplished his first priority is a mixture of the two scenarios which we felt most likely to occur. Xi secured his “Xi Jinping Thought,” emerged from the 19th Congress as a “General Secretary Plus,” and was able to appoint many trusted officials to key Party positions. But the appointment of Han Zheng, a top Jiang faction member, to the Politburo Standing Committee suggests that Xi still had to accommodate the views of opposing Party factions and elders.

Stiff factional opposition also meant that Xi was less successful in fulfilling his second priority at the 19th Congress. Wang ultimately stepped down from Politburo Standing Committee and didn’t make the new Central Committee. In late October 2017, Wang appeared to have retired from elite politics. One of our five 19th Congress scenarios (Scenario 4, List ‘B’) accurately anticipates the present Politburo Standing Committee members, including their ranking and post.

Based on our research and understanding of CCP factional struggle, we believed that Xi would still find ways to accomplish the two priorities that we felt were at the top of his agenda. Wang Qishan’s appointment as vice president confirms our analysis.

At this point, the popular theory that Wang Qishan left the Politburo Standing Committee because Xi Jinping was unwilling to break unwritten Party retirement age norms and promotion procedures must be addressed. We are not fans of the theory for several reasons:

- Party norms are far less rigid or binding than many observers believe. Powerful Party leaders often alter norms when it suits their ends, i.e. Jiang Zemin crafting the “seven up, eight down” rule to force his rivals to step down from the Politburo Standing Committee.

- Xi is not an all-powerful, Mao-like “red emperor.” And even Mao had to back down in the face of opposition to his disastrous Great Leap Forward.

- The “Party norms and procedures” theory may appear to fit for Wang’s case, but it is less useful in evaluating the 19th Congress reshuffle on the whole. Several non-elite officials (“shuangfei,” or officials who are not full or alternate members of the 18th Central Committee) like Beijing’s Cai Qi became full members of the 19th Central Committee and even joined the Politburo—an outright “breach” of “Party norms and procedures.” Xi also didn’t appoint a successor and downsized the Central Military Commission (CMC), another break with past procedure.

We believe that Wang didn’t make the Politburo Standing Committee for two reasons: Fierce factional fighting and Xi’s alternate plans. Wang’s very successful anti-corruption campaign made him many enemies in the Party. He also inspires great fear in the Chinese officialdom: officials are said to prefer meeting the Devil to Wang Qishan, and some prefer suicide to being investigated by the Wang-led anti-corruption agency. Given the good number of rumors and insider information in circulation before the 19th Congress, it is very likely that Xi did seriously think about keeping Wang in the CCP’s top leadership body for another term. The Jiang faction and other Party elites who oppose Xi, however, probably lobbied Xi intensely to change his mind and even tried other measures to force Xi to abandon Wang (a fierce overseas smear campaign against Wang would be an example). Xi indirectly voiced his desire to preserve Wang during an emergency meeting in July 2017, but probably weighed that the move may prove too unpopular in the Party and even could affect his own standing should he force the issue. Instead, Xi likely came to a compromise with his rivals: In exchange for further consolidating his authority by adding the “Xi Jinping Thought” to the CCP charter and state constitution—another rumor that was floated before the 19th Congress—Wang would step down from the Politburo Standing Committee and the Central Committee. Xi ultimately got the highly symbolic political theory that places him at least on the shoulder of Deng Xiaoping in the pantheon of Party leaders, and further consolidated power. Wang exited the Party leadership—then abruptly “returned” to the spotlight in March.

From De Facto No. 2 to Actual No. 2?

We traced the signs of Wang Qishan becoming the next vice president and explored some possible reasons for his appointment in previous articles. A brief recap follows.

We were the first to predict Wang’s appointment as vice president, a deputy leader of the Party’s national security commission, and the possibility that he would be given a diplomatic portfolio. We also noted that Wang would be an unofficial Politburo Standing Committee member. His seating arrangement at a March 4 preparatory meeting for the first session of the 13th NPC confirms our analysis.

Starting November, various news outlets and observers started reporting about Wang’s return and his continuing to attend Politburo Standing Committee meetings as a nonvoting member. Reports also noted that Wang would handle Sino-U.S. relations. Wang’s return was practically confirmed when he was announced as a Hunan Province delegate to the Chinese legislature in January and left off the list of “old comrades” whom Xi and the Central Committee would visit over the Lunar New Year holiday.

We noted Wang is Xi’s best choice for the vice presidency because he is Xi’s most trusted ally, a veteran troubleshooter with economic credentials and experience dealing with U.S. officials, and won’t be mistaken for Xi’s successor due to his age. Because the vice presidency has no age limit and is traditionally a ceremonial state position (the Party hierarchy outranks the state hierarchy in China’s parallel system of government), we felt that Xi would face less internal resistance in selecting the much feared Wang for the job. And Wang’s possible “rivals” for the position are either in some form of trouble (Sun Zhengcai and Li Yuanchao) or are insufficiently qualified for the job (Hu Chunhua).

With Wang now back in the fray, we believe that Xi is set to repeat an earlier political play to gain additional yards against his factional opponents. We noted above that Xi likely compromised on keeping Wang in a top Party position because he may have alternate plans for his top ally. Our observation is based on Xi’s “Wang Qishan bluff” at the 18th Congress. The Jiang faction and other rivals of Xi probably presumed that Wang, then the sixth-rank Politburo Standing Committee and head of the unimportant Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, would not amount to much politically. Few, if any, would have expected Wang to shake up the Party and the balance of the factional struggle with a grinding anti-corruption campaign, much less become the de facto Party number two.

Beaten and bruised by Wang’s relentless anti-corruption efforts, Xi’s factional rivals decided to straitjacket Xi again by forcing his political enabler out of the ranks of the Party’s elite at the 19th Congress. They achieved the feat, but the move could yet return to haunt them. Xi has been gradually putting more emphasis on implementing the rule of law and in state institutions like the National People’s Congress and the National Supervision Commission. Cynics would argue that state institutions are still subordinate to the Party hierarchy and Xi’s gestures are empty, but under Xi’s watch, one of least powerful Party organs grew to become one of its most powerful. It would not be a stretch to imagine Wang becoming even more prominent as vice president and national security deputy leader than when he was the Party’s anti-corruption chief if Xi strengthens the role of state institutions. Indeed, observers may look back on Wang Qishan’s appointment as vice president as the moment that he went from being China’s de facto number two to a genuine number two.

Wang’s path to the vice presidency, however, was anything but smooth sailing. A timeline of political developments proves the case:

Jan. 18 – Jan. 19: The CCP Central Committee held its Second Plenum. Amendments to the state constitution were discussed at the plenary session, but only two changes (adding “Xi Jinping Thought” and legislation for the National Supervision Commission to the constitution) were announced in the Second Plenum communique.

Jan. 29: Wang Qishan was elected as a Hunan delegate to the NPC meeting at the Two Sessions.

Jan. 29 to Jan. 30: The list of constitutional changes discussed at the Second Plenum was submitted to the NPC Standing Committee for review and approval.

Feb. 25: The full list of constitutional amendments deliberated at the Second Plenum was announced. One of the changes was removing presidential and vice presidential term limits. The announcement was unusual because it should have been made after the NPC Standing Committee meeting at the end of January.

Feb. 26 – Feb. 28: The Third Plenum of the 19th Central Committee was convened. Discussed at the meeting were issues of political and economic institutional reform, as well as the candidates for key state positions who were to be formally appointed at the Two Sessions.

In our article on why Xi Jinping removed the presidential term limits, we wrote that Xi likely encountered massive resistance to the move. Given that the feared Wang Qishan would be granted “indefinite” rule as vice president alongside Xi, it is no wonder that Xi met with strong opposition. Indeed, Wang now has virtually unlimited time to help Xi eliminate his political rivals, a catastrophic (and likely not anticipated) scenario for Xi’s political enemies.

Changing the Rules

Xi Jinping may be sincere about pushing reform in China, but a life-and-death factional struggle is the driving reason for why he is rejecting Jiang era policies and the changing the rules of the political game.

The Bo Xilai affair and the Jiang faction’s attempted coup before the 18th Congress signaled to Xi that he would have to eliminate the Jiang faction for his personal safety and that of his allies. Dismantling his rivals and their power networks would also allow Xi to push through his own policies and not have them stymied at the earliest opportunity. For instance, Xi talked about a “constitutional dream” alongside his “China dream,” but the former idea wasn’t promoted by the Jiang faction-controlled propaganda apparatus and was eventually dropped altogether. Also, Li Keqiang, a Xi ally, met with massive resistance in setting up the Shanghai Free Trade Zone in 2013. Li was reportedly so frustrated with the experience that he pounded his fist on the table in anger and boycotted the project’s opening ceremony. Furthermore, despite promising sweeping economic reforms at the Third Plenum, Xi was unable to make any headway because the Jiang faction and influential Party princelings held sway over the economy through their ownership of key industries.

Factional fighting made it imperative for Xi to switch up how things were run in China. The anti-corruption campaign served the dual purpose of weakening the Jiang faction and disincentivizing the officialdom from destabilizing the regime through rampant corruption. The new anti-organized crime campaign looks to build on the anti-corruption drive, as well as allow Xi to clean out Jiang networks in the domestic security and legal apparatus. The Xi administration’s emphasis on the rule of law and constitutionalism is anathema to the Jiang faction, whose members were often deeply involved in corruption, kleptocracy, and persecution. Indeed, it can be argued that the Xi administration is slowly shifting the regime’s stance on the persecution of Falun Gong, Jiang Zemin’s pet project, partly to deter Jiang faction mischief and partly to ease China’s financial woes. To sustain the persecution campaign, Jiang pumped vast sums of money into the regime’s domestic security and legal apparatus (under Zhou Yongkang, the domestic security apparatus enjoyed a budget higher than that of the military) and promoted loyalists to top positions. So when Xi took office, he inherited a domestic and legal apparatus that largely opposed him and dragged their feet on implementing his policies, and his administration was saddled with a heavy financial burden.

Some observers have argued that Xi’s power consolidation at the 19th Congress allows him to boldly push reform. Others argue that Xi may find it difficult to implement reforms as officials fear getting punished for making mistakes. We believe that the situation is less straightforward. From the perspective of factional struggle, Xi needs to clean out the Jiang faction and consolidate power if he is to successfully push through any substantial reform at all. For example, Xi’s latest plan to tackle “major risks” in the financial sector seems to involve reining in Chinese conglomerate executives with friendly ties to the Jiang faction and purging corrupt officials, alongside adopting the usual financial deleveraging tools. By contrast, the lack of focused anti-corruption action and tough regulation after the Third Plenum of the 18th Congress, a period where Xi was still in the nascent stage of power consolidation, meant that the Xi administration was able to achieve almost none of its proposed economic reforms.

Yet Xi having more power doesn’t necessarily equate to reform success. Towards the latter half of his first year in office, anti-corruption officials and at least one notable Chinese scholar highlighted the problem of “lazy” officials who chose to sit on their hands instead of carrying out orders from Beijing. We believe that the laxness of officials is partly due to uncertainty over what is the “politically correct” thing to do in the Xi era, and partly because officials are closely watching the Xi-Jiang factional struggle and waiting to see which side prevails before picking a side and agenda to back.

Foreign companies in China who were unaware of the new political rules under Xi are at great risk. Several big firms were fined hundreds of millions of dollars as the factional struggle crossed into the financial sphere. Other companies that made political investments in would-be CCP leader “successors” like Sun Zhengcai and Chen Min’er may not be able to see political or monetary returns as Xi purged Sun in 2017 and didn’t designate a successor at the 19th Congress.

A History of Violence

The Wang Qishan case demonstrates the primacy of CCP factional struggle in determining key appointments and policy directions. And factional struggle occupies a central role in elite Chinese politics. We are able to anticipate political developments and the direction that China is heading because we understand the logic behind CCP factional struggles.

Factionalism has existed since the CCP’s foundational years. Mao Zedong once acknowledged that the forming of Party factions is an inevitable phenomenon. After the CCP took power in China, factional fighting tended to revolve around succession politics for one reason—mass bloodshed. Party leaders tended to carry out several political campaigns during their term, and some of which turn out to be particularly murderous affairs. Think Mao’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping’s Tiananmen Square massacre, and Jiang Zemin’s persecution and organ harvesting of Falun Gong adherents. Fearing denouncement and a tarnished legacy (not mere paranoia given what Nikita Khrushchev did to Joseph Stalin) or being purged (if alive), Party leaders removed designated successors who they feel will be less supportive of their policies (like Lin Biao and Zhao Ziyang). To safeguard their bloody legacy, Party leaders also prefer to pick successors who back their butchery and preferably have their hands bloodied as well. Deng picking Jiang (supported the use of force at Tiananmen) and Hu Jintao (authorized deadly force in suppressing a Tibetan uprising) is an example. The idea behind this selectivity is that guilty Party leaders would be less keen on prosecuting their predecessor for fear of being themselves outed as a serial murderer. In other words, the guilty wouldn’t indict the guilty. Regardless, tensions still exist between Party leader and successors, and these tensions play out in factional struggles.

Factional fighting since 2012 has been particularly intense because mass bloodshed is absent from Xi Jinping’s career. Xi is also at risk of being disposed of in a Jiang faction coup owing to his unclear stance on the persecution of Falun Gong. In an earlier article, we provide analysis and evidence of prior Jiang faction coup attempts. Xi’s trusted officials have also made forthcoming remarks about failed coups by Jiang faction members. For instance, top securities regulator Liu Shiyu and CCP General Office head Ding Xuexiang have accused Bo Xilai, Zhou Yongkang, Xu Caihou, Guo Boxiong, Sun Zhengcai, and others of having sought to “usurp the Party leadership.”

A Struggle for Legitimacy

From a macro view, CCP factional struggles exist because the CCP has never been able to adequately resolve the issue of its political legitimacy.

Rulers and aspiring rulers of China struggled with the question of why they should be allowed to govern the country, and came up with various solutions. Since the Zhou Dynasty, kings and emperors adhered to the idea of a Mandate of Heaven, or the right for a monarch to reign long as he remain virtuous. Successful rebellions by noble houses (Qin and Tang) or even by commoners (Han and Ming) were taken as a sign that a ruler had lost the Mandate. The Mandate idea fell out of favor after Dr. Sun Yet-sen popularized the idea of a democratic republic at the turn of the 19th century. Sun’s “Three Principles” would later be adopted by the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) when it founded the Republic of China (ROC). In 1949, the CCP seized power from the Kuomintang after a bloody four-year civil war, and Mao proclaimed the right to rule on the idea of the communist revolution and utopia. The Chinese people, however, were disillusioned with founding a communist paradise and one-man rule after Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. To restore the CCP’s credibility, Deng Xiaoping tied the Party’s political legitimacy the delivery of economic prosperity for people and country, and shifted the Party towards rule by consensus via a “collective leadership” model.

The “collective leadership” model, however, has proven ineffective in shoring up the CCP’s legitimacy claim. Jiang Zemin spread corruption, kleptocracy, and persecution in China, and later used an expanded Politburo Standing Committee stacked with his allies to shackle Hu Jintao to his policies via “consensus” rule. The China that Xi Jinping inherited from Hu had few honest officials and military generals, as well as severe economic problems and financial risks. To fix China’s problems, Xi needed to wrestle power away from the Jiang faction. And the only way that Xi could consolidate his authority was by ruling as a classic Party authoritarian and resorting to the Party’s repressive tendencies. Hence observers noticed a return of the Party in the daily lives of Chinese people, tighter internet and media restrictions, increased suppression of the populace in some instances, and the mass arrest of corrupt officials. After all, power and authority in the CCP is built on resolving crises and dangers. Like a snake consuming its tail, Xi is bringing the Party back full circle—one-man rule—to preserve its legitimacy.

Given the nature of the CCP dictatorship, Xi will unlikely resolve the Party’s legitimacy problem or the issue of succession. Barring radical political reform, the Chinese regime is headed towards an unending cycle of factional struggles as the different political cliques adapt to the Xi administration and exploit loopholes in the system to their advantage. Xi appears to be aware of the CCP’s death spiral, and has been nudging the regime towards constitutionalism and the rule of law, and away from the status quo where the Party is the law. It is too early to say whether or not Xi will succeed in overhauling the system. But if Xi does push through his reforms, the very nature of the CCP dictatorship itself will be in question.

Conclusion

The rules of elite Chinese politics changed at the 18th Party Congress, and changed again at the 19th Congress. Key to understanding the changes and developments in elite Chinese politics is knowledge of CCP factional struggle, its logic, and being able to differentiate the factional background of officials.

Our knowledge of the core issue behind modern CCP politics and factional struggle allows us to craft a unique research methodology to anticipate personnel movement and other key political developments undertaken by the Xi Jinping leadership.