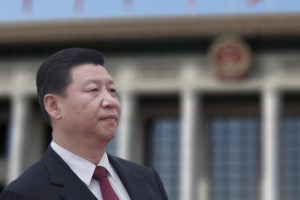

◎ We believe that the answer to why Xi removed term limits for the Chinese presidency can be found in an analysis of CCP factional struggle.

By Don Tse and Larry Ong

Chinese state media published a list of constitutional changes deliberated by the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Central Committee on Feb. 25. Among the amendments include the removal of term limits for China’s president and vice president.[1]

News that China’s Xi Jinping could potentially be president for life sparked an international uproar. Observers described the move as a “power grab,” a return to “one-man rule,” and the end of reforms in China. Xi was likened to Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Chairman Mao Zedong. Financial analysts noted that Xi’s lifelong tenure could mean more stable markets but increased systemic risks owing to the nature of dictatorship. Some China experts, however, sensed that something was not “normal” in the Chinese regime.

We believe that the answer to why Xi removed term limits for the Chinese presidency can be found in an analysis of CCP factional struggle (neidou). Since taking office in 2012, Xi has been engaging in a life-and-death contest with Jiang Zemin’s influential political faction. For self-preservation, Xi rolled out several political reforms that helped him consolidate power and marginalize the Jiang faction. One of the latest reforms is the scrapping of presidential limits, a move that further strengthens his authority and paves the way for the implementation of even more significant political reforms.

At this juncture, a clarification of what we mean by political reform is in order. To international observers, political reform in the context of illiberal states is typically understood as a move towards liberalization and democracy. In the Chinese regime, however, political reform refers to less drastic measures like restructuring bureaucracy, rebalancing power among the various Party organs and state apparatuses or even between the Party and state hierarchies, or the creation of new administrative bodies. Our mention of Xi’s political reforms refers to the latter definition.

We also challenge the notion that Xi is aiming to be the second Mao by examining Xi’s unusual focus on the presidency and his constitutional turn from a historical perspective. In fact, we believe that it is inaccurate to compare Xi to any Party or world leaders from past and present after an examination of his reforms and policies.

Factional deathmatch

We explored the Xi-Jiang factional struggle and Xi’s reforms at some length (but not exhaustively) in previous essays. A brief recap is required here to contextualize the CCP’s recent constitutional changes. (Those familiar with the CCP neidou can skip this section.)

Xi Jinping came to office in a hugely disadvantageous position. The Jiang faction had dominated the political landscape for nearly two decades, and controlled important CCP organs like the domestic security and legal apparatus. The Jiang faction also controlled the financial sector. While Xi is a Party princeling (his father was a founding revolutionary alongside Mao Zedong), he wasn’t aligned with any influential Party factions, nor did he seek to establish one of his own. Xi’s lack of supporters is evident from his personnel picks for senior positions at the provincial level and above. Presently, less than a quarter of provincial Party secretaries are Xi’s former colleagues, schoolmates, or aides. Indeed, Xi now appears to be heading in the direction of “one-man rule” partly because he lacks a faction and sprawling political networks to control the Party through informal means. But in 2012, Xi had very little political clout.

The Jiang faction wishes to dispose of Xi for several reasons. First, Xi was a compromise candidate between Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, and Jiang always meant to replace Xi at a later date with officials who are friendly with his faction and support his policies. More crucially, Xi was a political risk liability for Jiang because Xi’s stance on the persecution of the Falun Gong spiritual community, Jiang’s pet project, was unclear at best. A study of CCP leadership succession shows that Party leaders with bloodied hands (all except Xi) prefer successors whose hands are also soiled. Finally, Xi’s reforms and policies over the past five-plus years have worked to squeeze the Jiang faction to the brink.

The Jiang faction has resorted to a myriad of measures to undermine the Xi administration, the most severe of which are coups. Coups usually end badly (including loss of life) for the ousted party in authoritarian regimes like the CCP, hence our characterization of the Xi-Jiang factional fighting as a life-and-death struggle. Thus far, the Jiang faction has plotted at least two political coups (2012 and 2017) and one financial coup (2015). The Xi administration has responded with purges and even open signaling of the Jiang faction’s coup efforts. In a 2015 speech, Xi accused Jiang faction members Bo Xilai, Zhou Yongkang, and others of plotting “political conspiracies to wreck and split the Party.” During a 19th Party Congress meeting in October 2017, top securities regulator Liu Shiyu blamed the officials Xi mentioned earlier and fallen Politburo member Sun Zhengcai of plotting to “usurp the Party leadership.” Liu’s remarks on usurpation (cuan dang duo quan) were echoed by CCP General Office director Ding Xuexiang during a Jan. 26 work meeting. Ding also revealed that virtually all of the officials who were purged after Xi took office were guilty of “political crimes” and other political problems.

To swing the factional struggle in his favor, Xi introduced several reforms to turn the regime away from Jiang’s model and consolidate power. A crucial part of Xi’s power consolidation in the CCP involves his collecting symbolic titles like “core” Party leadership (2016) and having his political theory (“Xi Jinping Thought”) enshrined in the Party charter (2017) and state constitution (2018). Xi was able to take on those tokens of power only after weakening the Jiang faction and bolstering his authority in the regime. The anti-corruption campaign targeted mainly Jiang faction members and supporters, and sought to reverse the culture of corruption that flourished during Jiang’s era of dominance (1997 to 2012). Xi’s military reforms served to modernize the People’s Liberation Army, break up entrenched Jiang networks in the People’s Liberation Army, and bring the Party’s “gun” under his control. Meanwhile, Xi has been promoting constitutionalism and the rule of law, and is making efforts to correct historical cases of judicial injustice and malfeasance. Xi’s constitutional turn is anathema to Jiang Zemin and his faction, who engaged in corruption, kleptocracy, and persecution. In fact, Jiang even strengthened the Party’s control over the judiciary and law enforcement apparatus by granting disproportionate power and a massive budget to the Political and Legal Affairs Commission (PLAC). Since taking office, Xi has greatly reduced the power and reach of the PLAC while elevating the judiciary, state institutions, and the constitution.

Getting in line

Xi Jinping didn’t enjoy much success in implementing some of his reforms during his first five years in office because he was still in the process of consolidating power. As mentioned above, the Jiang faction was opposed to the Xi administration and resisted its policies. For instance, Chinese premier Li Keqiang reportedly pounded his desk in frustration when his plans for the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone were repeatedly scuppered or altered by Jiang faction elements in Shanghai. Li later boycotted the free-trade zone opening ceremony. Meanwhile, other officials disgruntled by the anti-corruption campaign and unsure of whether Xi or the Jiang faction were ahead in the factional struggle appeared to sit on their hands until the neidou results became clearer. The problem of official inaction and procrastination (bu zuo wei) eventually became so severe that anti-corruption officials started addressing the issue in their inspection reports of government departments and work units in the latter half of Xi’s first term. The anti-corruption agency even accused purged Chongqing chief Sun Zhengcai of being “lazy and indolent” as one of his many crimes, the first time procrastination became an official charge. With so many officials, including high-ranking ones, loafing about because they are uncertain about the state of the Xi-Jiang factional struggle, it is little wonder that Xi’s attempts at reform saw mixed results.

In theory, Xi should have few problems in advancing reforms after the 19th Party Congress. For instance, the addition of “Xi Jinping Thought” to the Party charter places Xi at least on the same level as Deng Xiaoping in the pantheon of CCP leaders. Many of Xi’s trusted officials were installed in key Party posts, and Xi appears to be a “General Secretary Plus” in a Politburo Standing Committee that is stacked with his allies and supporters (six to one). Observers believe that Xi may even be the strongest Party leader in decades.

By the logic of CCP factional struggle, however, Xi’s present political dominance has not yet found solid footing. Power is a long game in authoritarian regimes, and Xi’s opponents and the officialdom at large would likely regard him as merely having the advantage for the next five years, or until he has to give up the presidency under the old limits. Thus, many officials will continue to monitor the progress of the Xi-Jiang struggle and procrastinate in implementing policies from Beijing. Also, while Xi clearly didn’t pick a successor at the 19th Congress, Party elders may eventually find excuses to force Xi to designate the next CCP General Secretary (and not necessarily a candidate of his choosing) before his term is up. In other words, Xi may have more fully consolidated power in the Party, but the power struggle is still a factor because the Jiang faction still lingers and Xi’s authority is constrained by his remaining time in office.

Removing the presidential term limits is Xi’s answer to the political problems mentioned above. By opening the possibility that he could be China’s president indefinitely, Xi is also indicating that he could likewise serve as General Secretary and Central Military Commission chairman for life. If Xi intends to rule for three or more terms, he has good reason to rebuff Party elders who may not be inclined to witness a repeat of Mao and Deng’s designated successor problems. Meanwhile, the bulk of Chinese officials would be more inclined to get in line with Xi’s reforms when his rule is no longer bound by time constraints. After all, unending Xi rule means a perpetual anti-corruption campaign (plus the new anti-organized crime drive) and a higher probability of the Jiang faction being eliminated. To protect their self-interests over the long term, officials would gradually throw their weight behind Xi.

Xi’s solution to his reform problem, however, comes with challenges. In examining the Feb. 25 announcement of the constitutional changes and other developments, we believe that Xi met with fierce resistance inside the Party when he tried to drop the presidential limits.

The Second Plenum of the 19th Central Committee was held from Jan. 18 to Jan. 19, and all constitutional amendments discussed during the plenary session should have been finalized on the last day of the plenary session. The Central Committee then submitted the list of amendments to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) on Jan. 26, and the NPCSC should have deliberated the list during a key meeting on Jan. 29 to Jan. 30. Going by precedent, state media should have announced the constitutional changes around the period of the NPCSC meeting near the end of January. Instead, state media published the amendments nearly a month later. Furthermore, the amendments were published with only days to spare before the Third Plenum (Feb. 26 to Feb. 28), a conclave where important political and economic reforms are scheduled to be discussed. The time gap between announcements is very unusual, and indicates that Xi needed time to convince the 204-member Central Committee to digest and consent to the changes that he sought.

Two prominent arrest cases just before the Feb. 25 announcement also suggest that Xi Jinping is thinking about resistance from the Party at large to his dropping the presidential limits. On Feb. 23, Chinese regulators announced the takeover of Anbang Group and the prosecution of its chairman Wu Xiaohui. The following day, the Chinese authorities announced that Yang Jing, secretary general of China’s State Council, was removed from his posts, demoted from a deputy state-level official to a ministerial-level official, and handed a year-long Party probation. The official notice of Yang’s punishment noted that he had “confessed to his wrongdoing and expressed remorse.” We believe that Xi is sending a message that officials who surrender and fall in line with his administration like Yang Jing will be treated with leniency, while troublemakers like Wu Xiaohui will be punished regardless of their political status (being the grandson-in-law of Deng Xiaoping, Wu is considered a Party princeling). Put in another context, officials who resist Xi’s “indefinite” reign will be severely punished, while those who support him may be let off lightly if they are investigated for corruption.

The timing of Liu He’s United States trip also makes sense in light of the Feb. 25 announcement. Liu, a trusted ally of Xi, was scheduled to be in Washington D.C from Feb. 27 to March 3 to hold trade talks with Trump administration officials. While Liu technically has reason to participate in economic talks with the U.S. since he is the director of the Party’s Leading Group for Financial and Economic Affairs and Sino-U.S. trade tensions appear to be rising, there is little reason for Xi to dispatch him to D.C. at this time. Liu, a Politburo member, will miss the important Third Plenum because of his U.S. trip. Protocol-wise, Liu has not been officially appointed to a state job yet (he is tipped to be a State Council Vice Premier), and it is unclear in what capacity he will be negotiating with American officials. More suspiciously, the Sino-U.S. trade situation doesn’t appear to be so dire that a Politburo member with no state appointment needs to skip a plenary session and confer with officials from the Trump administration for five days. A plausible explanation for Liu He’s trip is that Xi feels the need to update the Trump administration on the implications of the presidential term limit change and what it entails for Sino-U.S. relations going forward.

‘Constitutional idiot and anti-Party element’

In commenting on the removal of presidential term limits, many international observers expressed fear that Xi Jinping is on the path to becoming the next Mao Zedong. From a historical perspective, however, we believe that Xi is in fact heading in the opposite direction from Mao.

Xi has placed much emphasis on constitutionalism since taking office. A month after taking office in November 2012, Xi talked of a “constitutional dream” (“xian fa meng”) in his third-ever speech as General Secretary. “The constitution’s foundation rests in the people’s heartfelt endorsement, and the constitution’s power rests in the people’s sincere faith in it,” he said in the speech. In July 2015, the Chinese legislature passed a decision that required all civil servants in China to pledge allegiance to the constitution when taking office. The first pledges of allegiance, which contain no reference to the CCP, were recited in January 2016. And in his marathon 19th Congress speech, Xi said: “No organization or individual has the power to overstep the constitution or the law; and no one is allowed in any way to override the law with his or her own orders, place his or her authority above the law, violate the law for personal gain, or abuse the law.” The latest changes to the presidential term limit make it constitutional for Xi to stay on indefinitely as head of state.

Mao would not have approved of Xi’s constitutional turn. The Great Helmsman believed that the Party should dominate everything and that constitutionalism was fool’s play. “Only idiots and anti-Party elements seek to distance themselves from the Party’s leadership and implement constitutionalism,” Mao reportedly said at a 1954 discussion forum on the state constitution.[2] In March 1957, he ordered schools to cancel lectures on the constitution and instead hold political lessons. In 1970, Mao repeatedly instructed officials working on constitutional amendments not to draft provisions for a presidency and that he had no desire in the position. Indeed, as Party Chairman and unquestioned dictator, Mao would have seen no need to abide by a set of rules governing the state when the Party and his word were law unto themselves.

Xi Jinping has accumulated immense power in the Party. For him to take the next step along the path of dictatorship and fully restore the primacy of the Party in China, Xi needs only to preserve the Party’s leading position and ignore the state hierarchy. He does not need to promote constitutionalism and strengthen state institutions.

Who is Xi Jinping?

If Xi isn’t on the way to becoming the next Mao, then how will he turn out with unlimited hold on power? Will he abandon political reforms and constitutionalism when his struggle with the Jiang faction is settled?

We believe that it is presently very tricky to anticipate where Xi is going with his reforms. To draw an analogy, criminal groups tend to abide by their own rules and behave in an anti-social fashion. For instance, if a gang boss wishes to partake in a Good Samaritan act, like helping an elderly granny cross a crowded street, his underlings might end up illegally stopping traffic and shoving aside passers-by to help their boss accomplish his task. Some observers have used the label “gangster regime” on the former Soviet Union, North Korea, and the CCP. And if Xi presides over a “gangster regime,” then his reforms and policies will be executed by Party cadres per crude CCP logic. This is why Xi’s push to alleviate poverty in China has seen the 2017 case of county officials in Guangxi over-reporting its poverty statistics (98 percent of the 3,000 “poor” were in fact not below the poverty line) to claim more financial support from the central authorities. Indeed, mainland Chinese media has observed that the CCP appears to be stuck in a “Tacitus Trap,” or a situation where the people presume that the government is dishonest regardless of what it does.

Deciphering the direction of political reform is also particularly challenging in authoritarian regimes because reforms that appear to strengthen a dictatorship could also end up paving the way for democracy. Take the case of Taiwanese dictator Chiang Ching-kuo. After succeeding his father Chiang Kai-shek, the younger Chiang proceeded to consolidate power by sidelining his political enemies in the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), imposing martial law, and clamping down on the press. At the apex of his power, however, Chiang lifted press and political party restrictions, ended martial law, and transitioned Taiwan to a democracy.

Taiwan, however, is not mainland China, and it would be foolhardy to equate Xi Jinping with Chiang Ching-kuo. Yet it would be just as reckless to liken Xi to Mao Zedong, Vladimir Putin, or other autocrats. Xi Jinping is Xi Jinping, and only he knows best the direction he is taking China. As for whether Xi’s rule is good or ill for the world, a clue can be found in President Donald Trump’s assessment of him after their April 2017 meeting, and Trump’s different treatment of Xi and China.

Conclusion

In sum, Xi Jinping removed presidential term limits because he needs to push through political reform. And Xi needs to be successful in his reforms to avoid ending up the loser in the Xi-Jiang factional struggle, a consequential political battle with dire implications for Xi and China. Contrary to what international observers believe, Xi’s position isn’t entirely stable, and he continues to face grave dangers and risks from factional rivals and the Party system itself. Finally, equating Xi with Mao or other past and present autocrats is erroneous given the reforms and policies Xi has pursued.

Notes

[1] Deng Xiaoping instituted the term limits in 1982, ostensibly to ensure the rotation of the top leadership positions and prevent a Mao-like dictator from emerging. The term limit safeguards, however, didn’t apply to him, a “retired emperor” (taishang huang) with power for life. As Central Military Commission chairman, Deng oversaw the appointment of five CCP General Secretaries and the removal of two. Later as a regular Party cadre, Deng successfully championed further economic reform in 1992. Clearly, constitutional limits were meant for lesser cadres.

[2] There has been some debate in recent years about whether Mao actually said those words, but at least two prominent individuals believe the statement to be correctly attributed. Xin Ziling, a retired defense official formerly at the PLA’s National Defense University, wrote in a treatise in a Chinese language periodical that Mao was known to belittle the constitution and that the statement was very characteristic of him. He Qinglian, a renowned Chinese economist, recalled reading the statement in a political pamphlet that was circulated during the Cultural Revolution.