◎ SinoInsider has been anticipating coming peace to the Korean Peninsula since Kim and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met in Beijing in March.

By Don Tse and Larry Ong

On April 27, the leaders of North and South Korea met at the demilitarized zone and signed a joint statement of “peace, prosperity and unification” of the Korean Peninsula. “South and North Korea confirmed the common goal of realizing, through complete denuclearization, a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula,” the statement read.

Before the talks at the inter-Korean summit began, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un write at the South’s Peace House guestbook: “A new history starts now. An age of peace, from the starting point of history.”

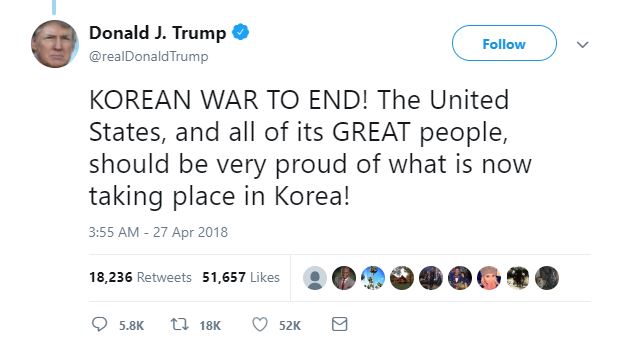

President Donald Trump welcomed the news. “KOREAN WAR TO END!” he tweeted. In a separate tweet, he wrote: “Please do not forget the great help that my good friend, President Xi of China, has given to the United States, particularly at the Border of North Korea. Without him it would have been a much longer, tougher, process!”

President Donald Trump welcomed the news. “KOREAN WAR TO END!” he tweeted. In a separate tweet, he wrote: “Please do not forget the great help that my good friend, President Xi of China, has given to the United States, particularly at the Border of North Korea. Without him it would have been a much longer, tougher, process!”

Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying said, “we applaud the Korean leaders’ historic step and appreciate their political decisions and courage.”

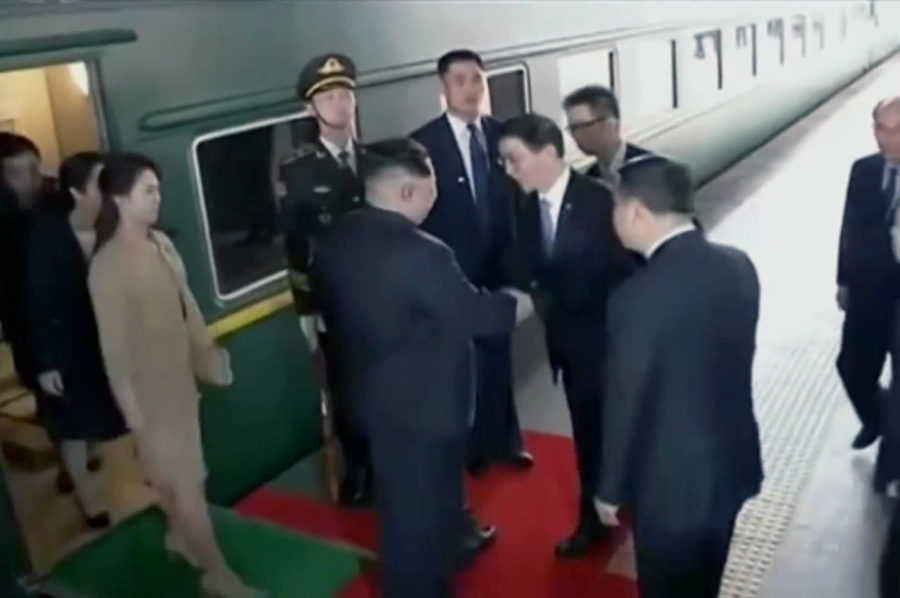

SinoInsider has been anticipating coming peace to the Korean Peninsula since Kim and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met in Beijing in March.

When news broke that Kim was secretly in Beijing, we wrote on March 26 that he could reach a deal with Xi where he gives up his nuclear weapons in exchange for an end to sanctions and retaining his rule over North Korea. “How Kim sells this deal to the North Korean elite and people would be his biggest headache,” we wrote.

When news broke that Kim was secretly in Beijing, we wrote on March 26 that he could reach a deal with Xi where he gives up his nuclear weapons in exchange for an end to sanctions and retaining his rule over North Korea. “How Kim sells this deal to the North Korean elite and people would be his biggest headache,” we wrote.

After the Xi-Kim summit was officially reported, we wrote on March 27: “If things on the Korean Peninsula continue along the current trajectory, Trump could eventually get North Korea to sign a peace treaty.”

On March 28, we wrote that the Xi-Kim meeting foreshadows peace on the Korean Peninsula.

On March 30, we wrote that “K-Pop diplomacy” on the Korean Peninsula indicates that Kim could carry out reform and opening up North Korea.

We believe that the April 27 inter-Korean joint declaration is a genuine step towards peace on the Korean Peninsula. Our prediction of coming peace is based on an analysis of what we believe to be the ultimate interests of the three main players in the North Korean crisis: North Korea, the United States, and China. In particular, Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy and Xi’s power consolidation play crucial roles in steering the North Korean crisis away from nuclear testing and towards denuclearization and peace.

Should negotiations continue to progress positively and at the current pace, we expect to see a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula within half a year after a peace treaty is signed. The denuclearization process should not take more than two years at the most.

Interests first

For the three key players in the North Korean crisis, the path to the peace and denuclearization talks was by no means straightforward or guaranteed. A country-by-country analysis follows.

North Korea

For authoritarian regimes, survivability of the ruling party or leadership is paramount. Communist regimes, in particular, have shown that they are willing to turn away from ideology or even slaughter their citizens if it means preserving the supremacy of the Party. To save the regime from Mao Zedong’s disastrous collectivism and legitimacy-damaging Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping promised to bring prosperity to the Chinese people (“to get rich is glorious”) and gradually liberalized the economy. Again to save the regime, he ordered the butchering of students at Tiananmen Square. Deng was successful, but his Soviet counterpart was not. Mikhail Gorbachev promoted “openness” and “restructuring” (glasnost and perestroika), but the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 because it could not fix its economic problems and overcome President Ronald Reagan’s efforts to “roll back” communism.

For authoritarian regimes, survivability of the ruling party or leadership is paramount. Communist regimes, in particular, have shown that they are willing to turn away from ideology or even slaughter their citizens if it means preserving the supremacy of the Party. To save the regime from Mao Zedong’s disastrous collectivism and legitimacy-damaging Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping promised to bring prosperity to the Chinese people (“to get rich is glorious”) and gradually liberalized the economy. Again to save the regime, he ordered the butchering of students at Tiananmen Square. Deng was successful, but his Soviet counterpart was not. Mikhail Gorbachev promoted “openness” and “restructuring” (glasnost and perestroika), but the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 because it could not fix its economic problems and overcome President Ronald Reagan’s efforts to “roll back” communism.

Like the Soviet Union and the CCP, the North Korean regime is most concerned with sustaining its rule. In 2013, Kim Jong Un launched his byungjin policy—pursuing economic and nuclear development simultaneously—with his regime’s long-term survival in mind. Kim’s policy led to minor market-oriented reform, as well as six nuclear tests and numerous intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launches. By the second half of 2017, North Korea claimed to have successfully tested a hydrogen bomb which it could be mounted on an ICBM, and later, an ICBM capable of hitting the U.S. mainland. U.S. defense secretary James Mattis said after the missile test that North Korea could target “everywhere in the world basically.”

Kim’s nuclear brinkmanship was met with international condemnation and stiff pushback from the U.S. and China. The United Nations Security Council unveiled the toughest ever sanctions against North Korea in September 2017, while the U.S. announced even stricter sanctions this February as part of a “maximum pressure” campaign. President Donald Trump also stepped up U.S. military presence in the region, held large-scale joint military exercises with South Korea, and threatened to use the “military option” against North Korea. Meanwhile, the Xi Jinping leadership took action by ordering Chinese banks to stop doing business with North Korea, shutting down trade along the China-North Korean border, and cutting off virtually all energy exports and imports from the Kim regime. In the first quarter of 2018, Chinese customs data showed that China was penalizing North Korea beyond what was required under U.N. sanctions, including no corn exports or shipments of diesel, gasoline and fuel oil. Economic experts say that North Korea would run out of hard currency as it uses its foreign reserves to finance the deficit with China, and could see a currency crisis in 2018 or by early 2019. In other words, Kim’s nuclear program was threatening to derail his plans for economic development and long-term regime survivability.

Kim’s nuclear brinkmanship was met with international condemnation and stiff pushback from the U.S. and China. The United Nations Security Council unveiled the toughest ever sanctions against North Korea in September 2017, while the U.S. announced even stricter sanctions this February as part of a “maximum pressure” campaign. President Donald Trump also stepped up U.S. military presence in the region, held large-scale joint military exercises with South Korea, and threatened to use the “military option” against North Korea. Meanwhile, the Xi Jinping leadership took action by ordering Chinese banks to stop doing business with North Korea, shutting down trade along the China-North Korean border, and cutting off virtually all energy exports and imports from the Kim regime. In the first quarter of 2018, Chinese customs data showed that China was penalizing North Korea beyond what was required under U.N. sanctions, including no corn exports or shipments of diesel, gasoline and fuel oil. Economic experts say that North Korea would run out of hard currency as it uses its foreign reserves to finance the deficit with China, and could see a currency crisis in 2018 or by early 2019. In other words, Kim’s nuclear program was threatening to derail his plans for economic development and long-term regime survivability.

Because regime survivability is paramount, we believe that Kim Jong Un would abandon his nuclear weapons and sign a peace treaty if he can get security guarantees from the U.S. and China. Kim has thus far shown himself to be a rational actor and not a madman (the blustery rhetoric of North Korean propaganda can be deceiving), and would not be so attached to the status of being a nuclear power as to forgo the chance to improve conditions in North Korea and preserve his rule.

Because regime survivability is paramount, we believe that Kim Jong Un would abandon his nuclear weapons and sign a peace treaty if he can get security guarantees from the U.S. and China. Kim has thus far shown himself to be a rational actor and not a madman (the blustery rhetoric of North Korean propaganda can be deceiving), and would not be so attached to the status of being a nuclear power as to forgo the chance to improve conditions in North Korea and preserve his rule.

Kim’s rush to negotiate with Xi and Trump suggests that the situation in North Korea is dire and that he needs to turn things around quickly. He has since demonstrated sincerity to denuclearize and have peace:

- Kim appears humbled before Xi in Chinese state media coverage of the Xi-Kim summit. This indicates that Kim has acknowledged his position as a loyal vassal to the Xi leadership, the first time since both leaders took office. (For more on the relationship between Xi and Kim, see the China subsection)

- According to South Korean president Moon Jae-in, Kim is willing to give up North Korea’s nuclear program without demanding that the U.S. withdraw its troops from the Korean Peninsula.

- Ahead of the inter-Korean summit, North and South Korea opened a direct telephone line between their leaders.

- On April 21, Kim announced that North Korea would be stopping nuclear testing and shutting down a major test site.

- At the inter-Korean summit on April 27, Kim and Moon agreed to hold talks with the U.S. and China on officially ending the Korean War. They signed the “Panmunjeom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula.” Key details include:

- Reconnecting families separated by the Korean War.

- Setting up an inter-Korean liaison office on the northern side of the demilitarized zone.

- Holding more inter-Korean high-level dialogues.

- Realizing “through complete denuclearization” and “a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula.”

Should coming negotiations with Trump and Xi turn out favorably, Kim’s chief concerns would be controlling the progress of liberalizing North Korea and selling denuclearization to the North Korean people. We believe that Kim’s April 21 statement sets him up to spin denuclearization in a manner which would not tarnish the prestige of his regime. Meanwhile, the K-Pop diplomacy after the Xi-Kim meeting suggests that Kim might be considering setting North Korea along the CCP’s path of reform and opening up under Deng Xiaoping.

United States

President Donald Trump’s approach to foreign affairs appears to be guided by his vision of making America influential and strong again. Resolving the threat of a nuclear North Korea and bringing peace to the Korean Peninsula would remove a dangerous national security risk and give America a foothold to reassert influence in the Indo-Pacific region as China encroaches. It is also in the interest of U.S. allies Japan and South Korea to see a nuclear-free Korea. Trump has already shown that he would not back down from his commitments (but he appears open to changing strategies or tactics to reach his end goals), and would unlikely compromise on his demands for North Korea to completely denuclearize. At a personal level, resolving the North Korean threat and bringing peace between the two Koreas would boost Trump’s bid for a second presidential term and seal his name in the history books.

President Donald Trump’s approach to foreign affairs appears to be guided by his vision of making America influential and strong again. Resolving the threat of a nuclear North Korea and bringing peace to the Korean Peninsula would remove a dangerous national security risk and give America a foothold to reassert influence in the Indo-Pacific region as China encroaches. It is also in the interest of U.S. allies Japan and South Korea to see a nuclear-free Korea. Trump has already shown that he would not back down from his commitments (but he appears open to changing strategies or tactics to reach his end goals), and would unlikely compromise on his demands for North Korea to completely denuclearize. At a personal level, resolving the North Korean threat and bringing peace between the two Koreas would boost Trump’s bid for a second presidential term and seal his name in the history books.

Trump has opted for a “maximum pressure” strategy to get Kim Jong Un to abandon his nuclear weapons and program.

On the economic front, the U.S. supports heavy United Nations sanctions that ban exports of equipment and machinery, energy and agricultural products, labor, and other resources or commodities to North Korea. The U.S. also imposes unilateral sanctions which are aimed at stopping individuals and businesses that support North Korea’s development of nuclear and missile technology, such as Chinese and Russian companies or banks.

On the economic front, the U.S. supports heavy United Nations sanctions that ban exports of equipment and machinery, energy and agricultural products, labor, and other resources or commodities to North Korea. The U.S. also imposes unilateral sanctions which are aimed at stopping individuals and businesses that support North Korea’s development of nuclear and missile technology, such as Chinese and Russian companies or banks.

On the military front, Trump has threatened to use the “military option” against North Korea if Kim crosses the red line. U.S. troops seem to be in a good position to actualize Trump’s threat. Presently, there are three aircraft carriers strike groups operating in the Western Pacific and B-2 bombers capable of carrying nuclear payloads in Guam. In December 2017, airborne troops and military helicopters carried out exercises at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, while reserve troops practiced setting up mobilization centers to move U.S. forces abroad quickly. This April, the U.S. and South Korean military held an annual joint exercise that involved 23,000 American troops and over 300,000 South Korean troops, as well as the unusual participation of F-22 and F-35 stealth fighters.

Trump’s strategy also involves getting the Chinese regime to cooperate. He appears to be adopting a two-pronged approach to ensure Beijing’s assistance in the North Korean crisis. First, Trump has frequently tapped into his good friendship with Xi Jinping in requesting that the Chinese regime do more to help with North Korea. And Xi appears to have reciprocated Trump’s exhortations on numerous occasions, such as with the banning of Chinese banks from doing business with North Korea in September 2017. Second, Trump gives the CCP “incentive” to complement U.S. “maximum pressure” tactics by rolling out a series of strong measures aimed at restoring parity in Sino-U.S. trade, punishing the Chinese regime for its intellectual property and other violations, and securing America’s national security. The proposed $150 billion tariffs on Chinese imports and the targeting of Chinese tech giants ZTE and Huawei, for example, are a painful squeeze on the Chinese regime’s key pressure points. The announcement of the trade and national security measures ahead of Trump’s summit with Kim Jong Un is likely designed to get the CCP to do its utmost to guarantee that America and China sign a historic deal with North Korea.

Trump’s strategy also involves getting the Chinese regime to cooperate. He appears to be adopting a two-pronged approach to ensure Beijing’s assistance in the North Korean crisis. First, Trump has frequently tapped into his good friendship with Xi Jinping in requesting that the Chinese regime do more to help with North Korea. And Xi appears to have reciprocated Trump’s exhortations on numerous occasions, such as with the banning of Chinese banks from doing business with North Korea in September 2017. Second, Trump gives the CCP “incentive” to complement U.S. “maximum pressure” tactics by rolling out a series of strong measures aimed at restoring parity in Sino-U.S. trade, punishing the Chinese regime for its intellectual property and other violations, and securing America’s national security. The proposed $150 billion tariffs on Chinese imports and the targeting of Chinese tech giants ZTE and Huawei, for example, are a painful squeeze on the Chinese regime’s key pressure points. The announcement of the trade and national security measures ahead of Trump’s summit with Kim Jong Un is likely designed to get the CCP to do its utmost to guarantee that America and China sign a historic deal with North Korea.

The China aspect of Trump’s strategy, however, was in fact dependent on whether Xi Jinping could get his house in order. Had Xi been unable to more fully consolidate power in the past half a year and convince the Chinese officialdom and Kim Jong Un that he was in ascendency, Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy would arguably be much less effective. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo perhaps indirectly revealed the importance of Xi’s power consolidation to resolving the North Korean crisis before the 19th Party Congress. “We think that President Xi will come out of this in a dominant position with incredible capacity to do good around the world,” he told Bloomberg in October 2017.

China

The CCP long has a geopolitical interest in North Korea. To safeguard its regime from U.S. “imperialist” allies South Korea and Japan, the CCP would unlikely give up communist North Korea as a buffer zone.

The CCP long has a geopolitical interest in North Korea. To safeguard its regime from U.S. “imperialist” allies South Korea and Japan, the CCP would unlikely give up communist North Korea as a buffer zone.

Xi Jinping, however, could not do much to rein in the Kim Jong Un regime until very recently. The Kim family is close with the Jiang Zemin faction, a once very influential Party interest group which rivals the Xi camp. The Jiang faction supported North Korea’s nuclear program, and when Xi came to power, North Korea became embroiled in the complicated affairs of CCP factional struggle. Indeed, the strength of the Jiang faction during Xi’s first term meant that he was limited to keeping his relationship with Kim virtually nonexistent and Sino-North Korean ties frosty. Xi did manage to take out Ma Xiaohong, a prominent Chinese businesswoman who is aligned with the Jiang faction and backed North Korea’s weapons program. But Kim Jong Un appeared to have remained unconvinced to switch allegiances from the Jiang faction to Xi.

U.S. pressure forced Xi and Kim to work on their relationship. As stated in an earlier section, Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign has sent North Korea’s economy into dire straits. Also, China cannot withstand a trade conflict with the U.S., and a full-blown trade war and crippling sanctions to China’s tech champions would have a disastrous effect on its economy. A calamitous economic crisis would seriously threaten the CCP regime as the CCP has connected its ruling legitimacy with economic performance since Deng Xiaoping. In other words, Trump’s China and North Korean policies were threatening the survivability of both communist regimes.

U.S. pressure forced Xi and Kim to work on their relationship. As stated in an earlier section, Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign has sent North Korea’s economy into dire straits. Also, China cannot withstand a trade conflict with the U.S., and a full-blown trade war and crippling sanctions to China’s tech champions would have a disastrous effect on its economy. A calamitous economic crisis would seriously threaten the CCP regime as the CCP has connected its ruling legitimacy with economic performance since Deng Xiaoping. In other words, Trump’s China and North Korean policies were threatening the survivability of both communist regimes.

The timing of U.S. pressure on China is also crucial in pushing North Korea. Had Trump rolled out his China trade measures before the Two Sessions in March, he might have found China to be less cooperative. To successfully pressure North Korea and ensure that the Chinese officialdom is largely in lockstep with him, Xi needed to consolidate authority over the regime to a very high degree and greatly weaken his political rivals. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign and military reforms had eroded the Jiang faction’s influence over the past five years, but he needed the final tokens of power and install top allies in key official positions to emerge from the CCP factional struggle as a clear winner. At the 19th Party Congress and the Two Sessions, Xi executed a string of political moves that solidified his paramount position and power:

“Xi Jinping Thought,” a symbolic political theory that puts Xi at least equal with Deng Xiaoping in the pantheon of CCP leaders, to the Party charter and state constitution.

“Xi Jinping Thought,” a symbolic political theory that puts Xi at least equal with Deng Xiaoping in the pantheon of CCP leaders, to the Party charter and state constitution.- The term limits for Chinese president and vice president were removed. This means that Xi could potentially stay in office forever. With Xi no longer a lame duck, Chinese officials who are allied with Xi’s rivals or have been passive about enacting his orders in hopes that things could go “back to normal” after his second term would be more inclined to side with Xi or become more active in executing his commands because their political careers depend on it.

- Xi named his allies to most key Party and state offices, including the propaganda apparatus, the military, and the financial regulators and central bank, and the public security ministry. Wang Qishan, Xi’s closest ally, was named Chinese vice president.

After having more fully consolidated his authority, Xi showed that he could exert decisive influence over North Korea and effect punishing sanctions. Kim was made to learn the hard way that Xi, and not the Jiang faction, was in charge. For instance, Song Tao, Xi’s special representative to North Korea, was given a cold reception when he visited Pyongyang for four days in November 2017. Subsequently, the Chinese regime ramped up sanctions. According to Chinese customs data, China’s total imports and exports in the first quarter of 2018 to North Korea dropped by 60 percent from the previous year. Imports alone fell by 86.2 percent. As written above, customs data also showed that China was imposing energy sanctions on North Korea beyond what was mandated by the U.N. Kim caved, and sought a meeting with Xi in Beijing in March. When Song Tao visited North Korea again after the Xi-Kim summit, Kim showed him a warm reception.

While Xi undoubtedly would want friendlier relations with North Korea, he appears to have been pushed into accelerating the process of reining in Kim by Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy. For instance, Kim’s Beijing trip took place after Trump signed an executive memorandum to impose $50 to $60 billion in tariffs on Chinese imports. Also, Trump’s comments about the North Koreans wanting the Trump-Kim summit to take place as quickly as possibly came after the U.S. commerce department banned suppliers from selling services or equipment to China’s ZTE for seven years, a potentially crippling move for the second-largest Chinese telecommunications company. The urgency of the North Koreans coincides with greater U.S. economic pressure on China, and indicates that Xi may be looking to secure a bargaining chip to de-escalate trade tensions. Based on our research, China cannot withstand a trade war with America, and needs to buy as much time as possible to deleverage and de-risk the financial sector and the economy.

While Xi undoubtedly would want friendlier relations with North Korea, he appears to have been pushed into accelerating the process of reining in Kim by Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy. For instance, Kim’s Beijing trip took place after Trump signed an executive memorandum to impose $50 to $60 billion in tariffs on Chinese imports. Also, Trump’s comments about the North Koreans wanting the Trump-Kim summit to take place as quickly as possibly came after the U.S. commerce department banned suppliers from selling services or equipment to China’s ZTE for seven years, a potentially crippling move for the second-largest Chinese telecommunications company. The urgency of the North Koreans coincides with greater U.S. economic pressure on China, and indicates that Xi may be looking to secure a bargaining chip to de-escalate trade tensions. Based on our research, China cannot withstand a trade war with America, and needs to buy as much time as possible to deleverage and de-risk the financial sector and the economy.

In sum, the Chinese regime’s effectiveness in controlling North Korea is contingent on Xi Jinping’s power consolidation. And Xi’s ascendency is tied with changes in elite CCP politics and the factional struggle.

What’s next?

Future peace and denuclearization talks would likely progress smoothly since the three main players in the North Korean crisis each have vested interests in the outcome.

North Korea

Kim Jong Un would likely wish to speed up negotiations to preserve his rule. Trump has made it crystal clear that he would not abandon “maximum pressure” short of North Korea making big concessions, and Kim would not want to drag out negotiations least his nation’s economic woes become too severe. Given Kim’s predicament, he might not be too insistent on the “phased denuclearization” approach. After all, Trump has declared that he would walk away from the table if negotiations weren’t showing results, or not hold the meeting at all.

Kim Jong Un would likely wish to speed up negotiations to preserve his rule. Trump has made it crystal clear that he would not abandon “maximum pressure” short of North Korea making big concessions, and Kim would not want to drag out negotiations least his nation’s economic woes become too severe. Given Kim’s predicament, he might not be too insistent on the “phased denuclearization” approach. After all, Trump has declared that he would walk away from the table if negotiations weren’t showing results, or not hold the meeting at all.

Should Kim agree to denuclearize, expect North Korean propaganda to spin the result as a “victory” for the regime. North Korea, China, and the U.S. could work out an arrangement where Kim gives up his nuclear weapons without tarnishing his reputation at home.

After denuclearization, North Korean propaganda would likely place increased emphasis on the new “strategic line” of economic reform. Kim could start a reform and opening up process modeled after the CCP’s experience. South Korea, Japan, China, the U.S., and other countries could play a key part in supporting North Korea’s economic liberalization for at least the next two decades.

North Korea and South Korea could work towards a plan for eventual reunification of Korean Peninsula.

United States

Trump has said that he would keep up “maximum pressure” until North Korea offers concrete concessions regarding complete denuclearization, and should stick to his word. Expect Trump to also keep the trade war card in play with China, but make concessions should the Xi administration continue to apply immense pressure on North Korea and help to sway Kim around to an agreeable denuclearization deal. Given the positive inter-Korean meeting, U.S. Commerce Secretary Steven Mnuchin could show a willingness to treat China less harshly when he visits the country for trade talks in the first week of May.

Trump has said that he would keep up “maximum pressure” until North Korea offers concrete concessions regarding complete denuclearization, and should stick to his word. Expect Trump to also keep the trade war card in play with China, but make concessions should the Xi administration continue to apply immense pressure on North Korea and help to sway Kim around to an agreeable denuclearization deal. Given the positive inter-Korean meeting, U.S. Commerce Secretary Steven Mnuchin could show a willingness to treat China less harshly when he visits the country for trade talks in the first week of May.

Trump would want Kim to give up all his nuclear weapons by 2020, or within his first term in office. South Korean newspapers report that Trump wants the denuclearization to be achieved within six months to a year, but not more than two years.

Trump is apparently open to positively helping North Korea if it cooperates. “If North Korea is willing to move quickly to denuclearize, then the sky is the limit. All sorts of good things can happen,” an administration official told The Wall Street Journal. We believe that Trump could indeed prove to be as magnanimous as he is tough with North Korea should Kim Jong Un agree to give up his nuclear program as per U.S. demands. Also, Trump would give Kim security guarantees, but would not withdraw American troops from the Korean Peninsula.

We anticipate Trump signing a peace treaty with North Korea and China if North Korea holds up its side of the bargain.

China

Xi Jinping should continue cooperating with Trump to push Kim Jong Un to accede to U.S. denuclearization demands. The Chinese regime would likely assist America in overseeing the confiscation North Korea’s nuclear weapons, as well as with supervising the dismantling of North Korea’s nuclear and missile program. The odds of Xi’s rivals undermining the denuclearization work are small because its proper execution concerns the survivability of the CCP.

Xi Jinping should continue cooperating with Trump to push Kim Jong Un to accede to U.S. denuclearization demands. The Chinese regime would likely assist America in overseeing the confiscation North Korea’s nuclear weapons, as well as with supervising the dismantling of North Korea’s nuclear and missile program. The odds of Xi’s rivals undermining the denuclearization work are small because its proper execution concerns the survivability of the CCP.

In exchange for his efforts to rein in North Korea, Xi would gain a crucial bargaining chip with Trump on trade. With the inter-Korean summit having gone smoothly, U.S. Commerce Secretary Mnuchin could announce some concessions during his trip to China in May.

According to Chinese language media, Xi is due to visit Pyongyang in June. We believe Xi could make his trip after the Trump-Kim summit, and that Xi and Kim would work out the details of a peace treaty during Xi’s visit. Xi could also request that Kim consider prioritizing the acceptance of China’s assistance for North Korea’s coming economic reform (and partly resolve China’s overcapacity problem); undoubtedly South Korea and its neighbors would be lining up to provide economic support for a liberalizing North Korea.

Conclusion

North Korea is the central actor of the “Cuban Missile Crisis” of the 21st Century, but the Kim Jong Un regime is not its star. Positive peace and denuclearization talks was brought about by President Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy and Xi Jinping’s successful power consolidation. Also, the importance of Xi’s ascendancy to the North Korean crisis is why understanding the role of elite CCP politics and factional struggle is paramount in making sense of and anticipating geopolitical developments in the region.

Given the positive inter-Korean summit, we expect the Trump-Kim talks to produce a historic outcome.