◎ The CCP faces seven pressing problems that render it unable to withstand a trade war with America.

The United States and China spent the first week of April ratcheting up trade tensions. But the Chinese Communist Party’s bark is louder than its bite, and the U.S. is just the opposite.

The backdrop:

On April 5, President Donald Trump directed U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to identify an additional $100 billion of tariffs on Chinese imports. At present, China is looking at 25 percent tariffs on $150 billion of products, while the U.S. faces 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion of exports.

Starting April 6, the CCP kicked into rhetorical overdrive. Spokespersons from the commerce ministry and foreign ministry declared that China would stay in the trade game “all the way” regardless of the cost, and would definitely find ways to retaliate.

In an April 6 commentary (“Who’s Afraid of $100 Billion? China Won’t be Intimidated!”), state mouthpiece People’s Daily accused the U.S. of “ignoring WTO guidelines,” and declared that “China won’t back down in the face of U.S. intimidation… [American tariffs will] definitely accelerate the pace of reform and opening up in China, and [China will] respond to U.S. containment action with more enthusiasm and higher quality development.”

On the same day, Trump said in an interview: “We’ve lost the trade war because for many years, whether it’s Clinton or the Bushes, Obama, all of our presidents before, for some reason it just got worse and worse. And now it’s $500 billion in deficits and a theft of $300 billion in intellectual property. So you can’t have this.”

Trump has said on several occasions that the U.S. doesn’t want a trade war but is looking for fair trade with China. He also requests that the CCP abide by WTO guidelines, open up China’s markets, and reduce the Sino-U.S. trade deficit.

At the Boao Forum for Asia on April 10, Xi Jinping promised to further liberalize China’s economy. He said that China “will only open wider” in the future, and pledged to open up the financial sector and the auto industry by this year, as well as expand protection for intellectual property, lower auto import tariffs, and increase imports in general. After Xi’s Boao speech, official rhetoric on the trade war began to cool.

Our take:

Xi would likely fulfill his Boao pledge and more. In examining China’s economic situation, the CCP faces seven pressing problems that render it unable to withstand a trade war with America.

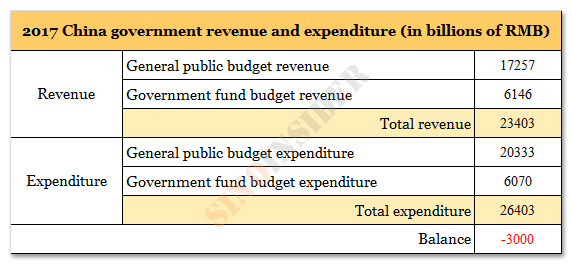

1. Historic fiscal deficit

Looking only at budgetary revenue and expenditures, China’s fiscal deficit hit a historic high of 3 trillion yuan (about $476.9 billion) in 2017. From 2011 to 2017, China’s full fiscal deficit rose from 39.5 billion yuan to 2982.1 billion yuan, or an increase of 6.5 times. The ratio of total deficit to total income in 2011 was 2.7 percent, but rose to 12.7 percent in 2017.

The CCP has issued treasury bonds to make up for the fiscal deficits, and the bonds issued each year has been steadily growing. For instance, the size of the national debt issuance in 2017 was 3.87 trillion, or 2.76 times higher than the 1.4 trillion in 2011. Also, 65.6 percent of government bonds issued in 2017 was used to repay old debts. This sort of inefficient borrowing means that the CCP will find it difficult to effectively recoup China’s fiscal deficit just by issuing treasury bonds.

Meanwhile, according to the 2017 fiscal gains and losses of the 31 provinces and municipalities in China, the planned cities of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen were the only regions that made surpluses.

Guangdong, the province that contributes the most financially, made fiscal contributions of only 628.8 billion yuan in 2017, a decrease from the 880.8 billion yuan in 2016. Shandong, the province with the third highest GDP in 2017 (7.27 trillion yuan), suffered a net loss of 4.4 billion yuan. Only a year ago, Shandong had a net surplus of 109.9 billion yuan. The 2017 fiscal figures show that the more affluent Chinese provinces who are supporting the central government are losing growth, while the other regions are getting poorer.

2. Declining exports, and reliance on exporting to the U.S.

After the world financial tsunami in 2008, China’s foreign trade industry entered a three-year “winter” period. But China’s net exports of foreign trade started to rebound from 2012 to 2015, a period which coincided with the Federal Reserve’s third round of quantitative easing (QE3) and a global economic recovery. By 2015, China’s foreign trade had reached a peak of $59.39 billion.

But QE3 ended in 2014, and China’s foreign trade import and export scale both started to decline in 2015. The scale of imports dropped more than exports, which saw a net increase.

In 2016, China’s net exports declined significantly. Exports in 2016 fell by 14.22 percent as compared to 2015, and fell again by 17.1 percent in 2017.

According to China’s official data, the country has always kept a foreign trade surplus, the bulk of which is made up of trade with the U.S. For nine of the past 11 years, China’s net exports to the U.S. accounted for over 50 percent of total net exports. In 2011, net exports to the U.S. were 30.62 percent higher than the national net exports figure. That is to say, China had an export deficit with other countries in 2011, and relied heavily on exporting to America to generate revenue.

3. Chinese manufacturing loses foreign funding; employment declines

From 2011 to end 2014, total employment in China’s three largest industrial enterprises above designated size (state-owned enterprises, private enterprises, foreign investment industries) rose from 73.43 million to 78.20 million. A decline soon followed. By 2016, employment in those three enterprises had fallen to 72.76 million, or a drop of 5.44 million (7 percent) since 2014.

Employment in state-owned enterprises declined to 16.96 million in 2016 from a peak of 18.93 million in 2012. Private enterprise employment fell 1.07 million between 2014 to 2016 (35.50 million to 33.98 million).

Employment reduction was the largest in foreign investment industries. In 2011, there were 25.74 million employed in foreign investment industries, but by 2016 the number had fallen to 21.82 million, or a decrease of 3.92 million. The ratio of foreign investment industry jobs to those in the three enterprises dropped from 35 percent in 2011 to 30 percent in 2016.

In the past 36 months, the “employed personnel index” sub-entry of China’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for the manufacturing sector was below 50 percent (contraction) each month except for March 2017. This indicates that employment in the manufacturing sector has been continuously decreasing, a reflection of a shrinking manufacturing industry where foreign investment is withdrawing from the mainland.

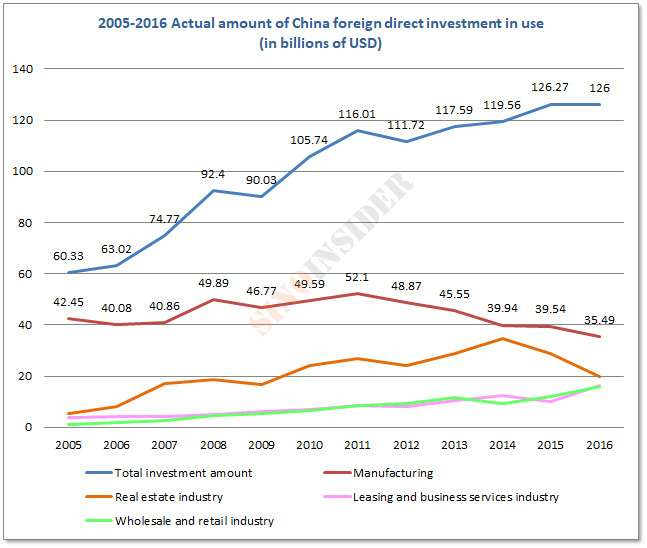

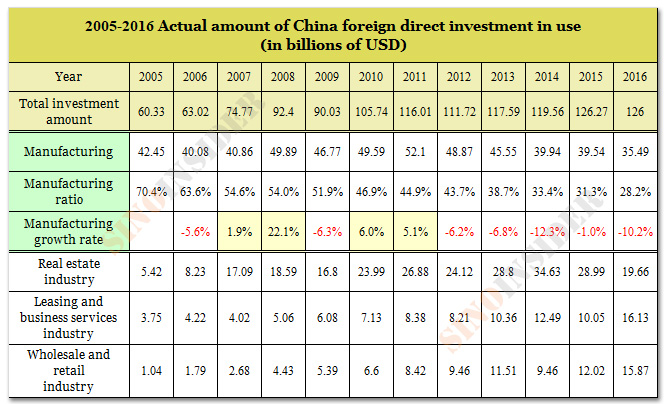

The above data shows that manufacturing is where most foreign investment goes to in China. Foreign investment started withdrawing after 2011, causing the manufacturing sector to shrink and employment to decrease.

The trend of foreign investments retreating from China can also be seen from foreign direct investment data. Foreign investment manufacturing peaked in 2011 ($52.1 billion), fell sharply by 12.3 percent in 2014 ($39.94 billion), and fell by more than a third in 2016 ($35.49 billion) as compared to 2011. This trend is consistent with China’s export situation.

In Dec. 2016, “Glass King” Cao Dewang announced that he was investing $1 billion in the U.S. to build factories. Cao, the chairman of Fuyao Glass Industry Group, said that profits are higher in the U.S. where taxes are 35 percent lower than China. He added that companies don’t have to pay for land in America and energy is much cheaper. Cao noted that electricity prices in the U.S. are half that of China, while U.S. natural gas prices are a fifth of China’s.

America’s more business-friendly environment has since gotten even more pro-business. Starting in 2018, companies pay a corporate tax of 21 percent, down from 35 percent. The U.S. corporate tax cuts essentially offset China’s labor cost advantage, its last remaining edge over the U.S. Looking ahead, foreign investment in Chinese manufacturing industries should further retreat from the mainland and return to the U.S. on a large scale.

Cao Dewang summed up the situation at the Boao Forum this April. “I think that Trump’s tax reductions are brilliant,” he enthused.

4. Soybean and food dependency issues

From 2013 to 2017, the total import value of China’s seven major food products (grain, meat, dairy, fishing, fruits, cooking oils, sugar) rose from $76.5 billion to $87.3 billion (about $560 billion yuan), while the ratio of food imports to China’s total imports rose from 3.92 percent to 4.74 percent. Since 2016, China has replaced the U.S. as the world’s largest food importer.

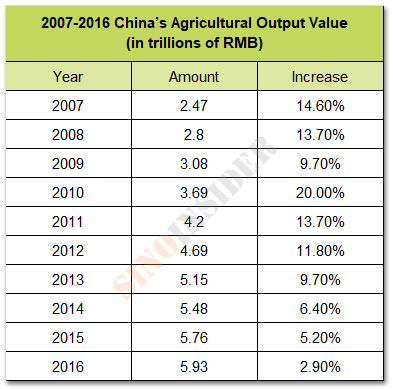

The growth rate of China’s total agricultural output value has been declining since 2011. In 2016, the growth rate fell by nearly half that of the previous year to 2.9 percent. In conservatively estimating the growth rate at 2.5 percent in 2017 and a total agricultural production of about 6.08 trillion yuan, that means that food imports in 2017 account for 9.2 percent of China’s total agricultural output value.

From 2011 to 2017, the total tonnage of grain imports more than doubled from 63.9 million tons to 130.62 million tons. In 2017, soybean imports reached 95.53 million tons, or 73 percent of total grain imports.

The CCP has been able to keep down domestic grain, meat, and cooking oil prices and prevent sharp rises in food costs by importing large quantities of low-cost, high-quality soybeans. The impending Sino-U.S. trade war, however, is having an impact on the CCP food strategy. Following the announcement of tariffs by China and the U.S., soybean meal (a crucial ingredient in farm feed) prices rose about 8 percent in the first week of April, or up 15 percent from the previous month.

5. Foreign-exchange reserves and RMB exchange rate woes

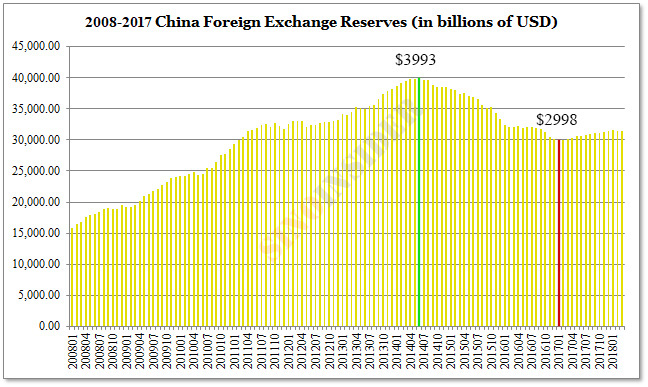

China’s foreign-exchange reserves peaked in June 2014 (nearly 4 trillion yuan) and started to drop in July 2014. The drop coincided with increasing back-and-forth in the CCP factional struggle. After taking office, Xi Jinping launched an anti-corruption campaign that chiefly targeted supporters and members of the Jiang Zemin faction in the Chinese officialdom. Meanwhile, Jiang faction officials sought to undermine Xi’s rule using various measures. The factional turmoil rocked CCP politics and the officialdom, triggering an immigration wave. As wealthy officials and businessmen scrambled to escape, capital outflows spiked.

Observers of elite Party politics noted that Xi’s factional rivals engineered the July 2015 China stock market crash. Xi ordered the deputy public security minister to make arrests, and the financial community was in a jittery state. In this turbulent atmosphere, the People’s Bank of China introduced exchange rate reforms on Aug. 11.

The central bank reforms resulted in a depreciation of the yuan. The RMB was devalued 2 percent against the dollar, causing panic selling in the global markets. By the end of 2016, the RMB exchange rate depreciated from 6.2085 to 6.9569 (10.75 percent decrease) to the dollar, and China’s foreign-exchange reserves dropped by $546.86 billion. In January 2017, the reserves fell below $3 trillion before slowly recovering. On March 26, 2018, the RMB exchange rate rose to 6.2680, while the foreign-exchange reserves stood at $3.1428 trillion. In other words, the RMB exchange rate is close to the level before the exchange rate reform, while the foreign-exchange reserves lost more than 400 billion yuan.

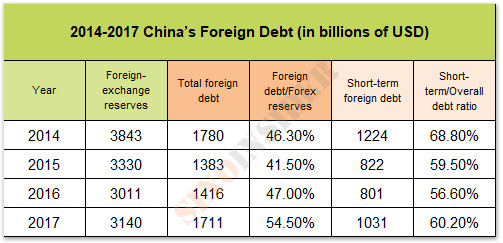

Looking at China’s foreign debt from 2014 to 2017, debt accounts more half of its foreign-exchange reserves, and its short-term debt reached a high of 60 percent. At the end of 2017, 82 percent of China’s debt in foreign currency was in U.S. dollars, and must be repaid in kind. China needs to repay 80 percent of its short-term external debt by the end of 2018. If half of the debt is counted as government liabilities, China will still need to repay $412.4 billion plus an additional $12.37 billion in interests (assuming an interest rate of 3 percent).

After Trump ordered additional tariffs on $100 billion of Chinese imports on April 6, the RMB exchange rate fell to 6.3056 to the dollar on April 10. Presuming that the exchange rate doesn’t fall, China will need to pay a principal and interest of $424.77 billion, an amount which would require an exchange of 2678 billion yuan.

The Chinese regime is running a huge deficit (see point 1). Without financial surplus, the CCP cannot simply touch its foreign-exchange reserves. The CCP can, however, print more RMB to exchange for dollars.

If the exchange rate falls by 1 percent, the Beijing would have to print an additional 26.78 billion yuan to pay off debts. Should the exchange rate drop by 10 percent, China will return to the early 2017 situation (6.9 RMB to the dollar) and would need to print 267.8 billion yuan. This is a very scary thing for inflation, and would contradict the Beijing’s deleveraging campaign and efforts to deflate the property bubble. So Beijing has to keep the exchange rate stable.

6. Ballooning real estate bubble and household debt

China’s real estate bubble inflated to its biggest yet in 2017. Both sales volume and figures were at record highs. Commercial housing sales totaled 13.37 trillion yuan (13.7 percent increase); total sales area was 16.94 trillion square meters (7.7 percent increase), of which 14.48 trillion square meters were residential buildings.

Real estate sales have been soaring since 2008 after Beijing released 4 trillion yuan to stimulate the economy. Over the next decade, real estate sales increased more than five times. The rate of increase spiked as high as 76.9 percent in 2009, and remains fairly high in recent years (34.8 percent in 2016).

As the real estate bubble grew, the leverage ratio of Chinese household debt approached the 50 percent benchmark, or that of the U.S. in 2007 before the subprime crisis. By the end of 2017, the balance of residential loans was 40.5 trillion yuan, meaning that the leverage ratio of Chinese residents (household debt/GDP) was at least 48.9 percent. In considering the many private financing channels (shadow banking, fintech, etc.) in China, the leverage ratio of Chinese residents could be much higher.

At the end of December 2017, the RMB real estate loan balance was 32.25 trillion yuan, an increase of 20.9 percent (5.56 trillion yuan) over 2016.

Due to the introduction of stricter real estate regulations in 2017, medium and long-term loans were limited, and the growth rate of individual housing loan balances saw a distinct drop from 2016. However, short-term loans for residents in 2017 increased by 1.83 trillion yuan, or an increase of 181.8 percent year-on-year. Many in the industry believe that the spike in short-term loans is related to the limiting of real estate loans. Some residents, analysts feel, will park their consumer loans in the property market after the loan limits are lifted in the future. Put another way, home mortgages form the bulk of Chinese household debt.

At the G20 central bank governors’ meeting in March 2016, then PBoC president Zhou Xiaochuan said that the logic behind the leveraging of individual housing loans is correct, and that there should be a phase where these housing loans are “vigorously developed.” He added: “In the case of China, the share of mortgage loans in bank loans is relatively low. In many countries, retail loans, especially mortgage loans, account for as much as 40%-50% in bank loans, while the share in China is at a relatively low level of between 10 and 20 percent. Therefore, the banks also consider mortgage loans as a relatively safe category of products, with rooms for further development.”

To put it plainly, the CCP encourages the Chinese people to take mortgage loans because it needs “household credit” to support economic growth when the real economy deteriorates. During this process, real estate debt risk is immediately transferred from the authorities to the people. Because China doesn’t have individual bankruptcy laws, the liabilities for individual housing mortgage loans are limitless. That means individuals have to continue paying their mortgages even after the bank confiscates their property.

In 2018, however, the CCP started talking about restraining household debt in a high profile manner. Why is this so? At the end of 2017, net household deposits decreased by 2.54 trillion yuan from 2016 to 23.88 trillion yuan. Meanwhile, the individual housing loan balance of 21.86 trillion yuan increased by 2.72 trillion yuan from 2016, and the leverage ratio of Chinese households was 91.54 percent. In accounting for illegal loans or loans being concentrated in first and second-tier Chinese cities, the leverage ratio of Chinese residents would exceed 100 percent, or even higher in first and second-tier cities.

Another way to understand the tremendous size of China’s real estate bubble is to study the growth model of HNA Group. The “HNA model” of growth is one that relies on ever-rising asset prices. HNA exploits continually appreciating land prices to secure financing, carry out leveraged global mergers and acquisitions, and proceed with equity pledge financing to expand its M&As. This Ponzi-like business model needs to keep borrowing to be sustainable, and would be difficult to upkeep once the environment in which ever-rising asset prices is gone.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) also sustain their growth rates through rising asset prices.

From 2013 to 2017, the total assets of state-owned enterprises rose from 91.1 trillion yuan to 151.7 trillion yuan (66.5 percent increase), while total liabilities increased from 59.3 trillion yuan to 99.7 trillion yuan (68.1 percent increase). The large increase of assets and liabilities took place simultaneously. Meanwhile, operating income only rose from 46.5 trillion yuan to 52.2 trillion yuan (12.3 percent increase) within the same period. In other words, SOE growth between 2013 and 2017 was not due to an increase in operating scale.

Indeed, SOEs appear to have been relying on the property bubble to drive up their asset prices. The sharp difference (40 percentage points) between the rise in SOE assets (66.5 percent) and commercial housing prices (26.5 percent) from 2013 to 2017 offers a clue as to how SOEs are riding the bubble. The simultaneous increase in SOE asset and liabilities suggests that the SOEs have been maximally pricing their assets when carrying out asset financing.

Given the state of China’s real estate bubble and financial sector leverage, Beijing would seek to maintain the asset bubble and shift risks to the people while it deleverages local governments, SOEs, and the banking sector.

7. Local government debt exceeds GDP

During a Two Sessions meeting on March 7, Shang Fulin, the former chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, suggested that Beijing should pay more attention to local government debts and the debt problems of administrations at the sub-provincial level.

Shang said that city-level secretaries and mayors whom he interviewed in an earlier investigation had complained that their regions were not ideal for attracting investments and that it was difficult to produce results in the short-term. When they were transferred out, their replacements were aghast at the situation they inherited from their predecessors. “Those city-level leaders said that stalls have already been set up and the money is spent, but investments still have to be brought in. What is to be done,” Shang said.

In the second half of 2017, Chinese provinces and cities began to tackle their government debts, as well as discern the scale of local government bonds and implicit debt. The results of this internal audit sounded alarm bells.

For example, a small town in Hulunbuir, a prefecture-level city in Inner Mongolia, was found to have accrued 300 million yuan in government debt as of end 2017, as well as an implicit debt of 1.5 billion yuan. Meanwhile, a county in Ningxia Province had a government debt of 696 million yuan and total liabilities of 2.828 billion yuan in the same period.

China’s local debt problems, when added up, spells trouble for Beijing. The finance ministry announced in 2017 that the balance of local government debt exceeded 16.47 trillion yuan. In conservatively estimating the implicit debt to be four times the official debt balance, total local liabilities could reach 82.35 trillion yuan, or 99.56 percent of China’s 2017 GDP (82.71 trillion yuan).

What’s next:

Given the seven problems identified above, China would end up the loser in a trade war with the U.S.

Should the CCP decide to go “all the way” against America, it faces a tsunami of problems that could lead to regime collapse. Chinese exports would be hit hard, foreign investment would withdraw from the mainland, the manufacturing sector would go under, and unemployment would skyrocket, and Beijing’s fiscal deficit would be even more severe.

As China’s foreign exchange earning capacity decreases, its foreign-exchange reserves would be reduced. And if the RMB exchange rate doesn’t have foreign exchange support, the yuan would depreciate and capital outflow would expedite. To repay foreign debt, Beijing would have to keep printing money, and banks would increase interest rates when confidence in the RMB falls. The devaluation of the RMB technically should promote exports, but it is unlikely that the depreciation would reach a stage where China can offset the additional costs of the 25 percent tariffs levied by the U.S.

Meanwhile, capital flight, bank interest rate hikes, and the collapse of the manufacturing industry would inevitably trigger a debt crisis and an asset selling spree. As asset prices fall sharply, the debt ratio of banking and financial institutions would soar. Government debt ratio would also spike, and it would accelerate the selling of assets to reduce the debt ratio. This scenario would lead to massive unemployment and bankruptcy in the Chinese middle class.

RMB devaluation and the soybean tariffs on the U.S. would lead to an increase in food prices. This affects the livelihood of all Chinese, particularly the underprivileged rungs of society.

In a China where many companies are going bankrupt, unemployment is on the rise, food prices are soaring, and the central authorities lack fiscal revenue to support its “stability maintenance” operations, the CCP is in grave danger. Even worse, the military, the Party, and state institutions have just undergone sweeping reform, and are in a particularly vulnerable state. The Chinese officialdom, which has been under stress since anti-corruption purges started in 2013, would be thrown into a state of greater instability. And under these circumstances, the CCP would be foolish to start a minor conflict abroad to draw attention away from domestic issues.

Thus, we believe that the Xi Jinping administration’s only option is to open up the markets, lower tariffs, and negotiate a compromise with the U.S. to avoid a trade war. But deciding how to open up China, and to what extent, will likely give the CCP endless bad headaches because China is trapped in a very unfavorable position economically, socially, politically, and geopolitically. Indeed, the CCP faces an existential crisis regardless of whether it opens up China or not.