◎ There are hints that the Meng Hongwei case is connected with a “soft coup” against the Xi leadership.

Updated on 12/3/2018

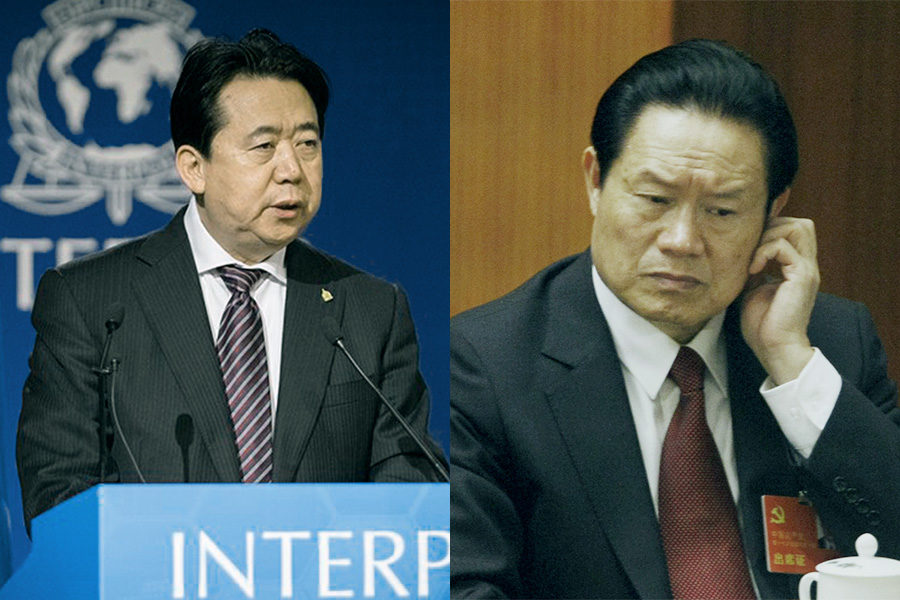

The sudden vanishing and investigation of Interpol chief Meng Hongwei has called renewed attention to the Chinese Communist Party’s pernicious behavior, human rights abuses, and political infighting.

Based on our research and understanding of CCP elite politics, we believe that the unusual and abrupt purge of Meng is a sign of serious trouble in the regime. Under usual circumstances, the CCP would refrain from inviting negative scrutiny upon itself by disappearing a senior official serving in a leadership role in a prominent international body. That Meng would be detained when there is extra scrutiny of the People’s Republic of China due to a trade war with the United States and several countries having national security concerns about CCP interference would seem like reputational suicide on Beijing’s part—unless dealing with Meng swiftly was paramount to resolving urgent internal challenges to Xi Jinping’s rule.

Meng’s arrest, when viewed in isolation, seems like part of Xi’s ongoing clean up of the regime’s domestic security apparatus, which continues to be swayed by Xi’s rivals. In juxtaposing Meng’s purge with recent public appearances by Xi’s political rivals and key commentary pieces in state media, however, there are hints that his case is connected with a “soft coup” against the Xi leadership.

The backdrop:

Sept. 25: Grace Meng, the wife of Meng Hongwei, told reporters that she received a kitchen knife emoji image four minutes after he sent a message saying, “Wait for my call.” She said that the knife emoji “means he is in danger,” and received no further texts from him. Meng was then back in China.

Oct. 3: According to Mingjing News, Meng Hongwei and an unnamed deputy minister-level official in the Ministry of Public Security were being investigated by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National Supervisory Commission. However, neither the CCDI nor the NSC had issued a formal announcement.

Oct. 5: The Interpol issued a statement about Meng’s disappearance and noted that the issue was a matter for the relevant authorities of France and China to settle and that the international agency would not comment further. According to the South China Morning Post, Meng was “taken away” for questioning as “soon as he landed in China” the previous week.

Oct. 6: According to Hong Kong newspaper Sing Tao Daily, Meng Hongwei was escorted away by CCDI officials when he landed in Beijing. Sing Tao added that Meng is suspected of “economic problems” and other corrupt activity.

Oct. 7: Grace Meng holds a press conference in Lyon, France about her missing husband. The CCDI issues a 26-character statement late on Sunday night announcing the investigation of Meng Hongwei, but leaving out charges. A few hours after the CCDI statement was published, the Interpol receive Meng’s resignation “with immediate effect.”

Oct. 8: The Ministry of Public Security holds a meeting on Meng Hongwei’s investigation. Zhao Kezhi, the public security minister, stresses the need to “resolutely eliminate the pernicious influence of Zhou Yongkang” the former security czar.

Radio Free Asia cites a source as saying that Meng and some of his subordinates are presently being held under house arrest in the outskirts of Beijing.

Oct. 10: In an interview with the Associated Press, Grace Meng said that she had received a mysterious phone call where a man threatened to send “two work teams just for you.”

The big picture:

Before Xi Jinping took office in November 2012, elite cadres in the Jiang Zemin faction attempted coups to prevent his ascension. Thus during his first term, Xi focused on eliminating his rivals and consolidating power in a bid for self-preservation. To that end, Xi launched a grinding anti-corruption campaign, embarked on military reform and modernization, and tried to get around the Jiang-era political system by working through Party leading groups.

Xi was successful to a degree. The anti-corruption campaign proved to be genuinely popular with the people, and the Party princelings (influential descendants of CCP revolutionaries) largely backed his purge of the Jiang faction because they believed that Xi’s anti-corruption efforts would be limited in scope. However, Xi was unable to properly implement his policies or push through reform due to resistance by the Jiang faction and the natural drag of Party culture. (“Reform” in the CCP context does not necessarily mean liberalization and a move towards democracy; we elaborate on Xi Jinping and reform in greater detail here.)

In his second term, Xi Jinping appeared to take action to eliminate resistance to his rule. Consolidating power to a very high degree would theoretically make governing easier in authoritarian states, and Xi moved to write his name into the Party’s constitution and remove term limits for the presidency. The continued personnel reshuffles in the military and government, and the sweeping government structural reform are aimed at breaking up entrenched interest groups and promoting more efficient governance. Meanwhile, Xi expanded the anti-corruption campaign to the domestic security apparatus, the financial sector, and the arts and entertainment industry. Xi’s actions, as well as his inability to prevent the outbreak of a trade war with America, seem to have made him new enemies in the regime while alienating the Party princelings who previously supported him.

Our take:

1. Based on our research, the CCP’s domestic security apparatus has long been in the hands of the Jiang Zemin faction. Since taken office in 2012, Xi Jinping has been scrubbing the security apparatus of the Jiang faction’s influence, most notably with the investigation of security czar Zhou Yongkang. After the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, we analyzed that a “thorough purge of the public security apparatus is forthcoming.” The disappearance and investigation of Meng Hongwei is the most high-profile instance of the public security apparatus purge.

During Jiang’s era of dominance (1997-2012), promotion of officials was largely influenced by Jiang faction officials in the various key organs and apparatus (Organization Department, Political and Legal Affairs Commission, etc.). In studying Meng’s rise up the ranks of the public security system in the early 2000s, it appears that he owes his promotion (and hence allegiance) to the Jiang faction.

Meng is a career public security official. In April 2004, he broke into the public security leadership ranks with his being appointed as vice minister of public security and a member of the ministry’s Party committee. In July 2004, Meng made deputy chief superintendent of the police, and by August, he was serving as director of Interpol’s National Central Bureau of China. In August 2011, Meng was tasked to head the counterterrorism leading group. From 2013 to 2017, he served as Maritime Police Bureau director and deputy director of China’s State Oceanic Administration.

Meng’s promotions coincided with Zhou Yongkang taking leading roles in the CCP regime’s domestic security apparatus. In December 2002, Zhou was appointed minister of public security. In November 2007, he became secretary of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission and joined the Politburo Standing Committee. Given the Jiang faction’s control over personnel movements, particularly in the domestic security apparatus, Meng Hongwei would have unlikely enjoyed smooth career progression if he had a fractious relationship with Zhou Yongkang. It should be noted that while Xi Jinping took office the 18th Party Congress in 2012, the Jiang faction continued to have decisive influence over key personnel appointments at the Congress and at least until the latter half of Xi’s first term.

There are two likely reasons why Xi Jinping “allowed” Meng Hongwei to serve as Interpol chief after his election in November 2016. First, Meng has been working with Interpol since August 2004, and his heading the international police organization is in the CCP regime’s larger interests. Second, Xi was having troubles reining in the public security apparatus at the time (see our analysis of the Lei Yang incident), and might not have wished to provoke more backlash by confronting Guo Shengkun, then public security minister and Jiang faction member, over the issue of Meng’s appointment.

Meng Hongwei’s career began to fade after Xi Jinping consolidated power to a greater degree at the 19th Party Congress and installed his ally Zhao Kezhi as minister of public security. In December 2017, Meng lost his offices in the Maritime Police Bureau and State Oceanic Administration partly due to departmental reorganization. In January 2018, Meng was appointed to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a subtle sign from Beijing that he could be allowed to enjoy a quiet retirement (Meng is 64, one year away from the official retirement age) provided he remains loyal to the Xi leadership. In April 2018, Meng lost his seat in the public security ministry’s Party committee. By late September, anti-corruption officials had gotten to Meng Hongwei.

In analyzing the current factional composition of the Ministry of Public Security’s Party committee membership, it can be argued that Xi Jinping only now more or less in control of the public security apparatus after six years as Party secretary. All eleven members of the Party committee were appointed after Xi took office, with six members clearly Xi’s allies, four being former colleagues of Xi in Fujian Province, and one a former colleague in Zhejiang Province. In particular, the top three members of the Party committee, Zhao Kezhi, Wang Xiaohong, and Deng Weiping, are allies of Xi. Meanwhile, former public security apparatus elites found themselves shunted out of the ministry this year. Three vice ministers (Fu Zhenghua, Huang Ming, Shi Jun) were transferred to other departments while two (Li Wei, Meng Hongwei) were removed from the public security ministry’s Party committee. The clear shift in factional composition of the Ministry of Public Security’s Party committee seems to have given Xi the assurance that he can move in on Meng Hongwei without rocking the public security apparatus too much.

The investigation into Meng could present Xi Jinping with a “breakthrough” to round up other former and serving domestic security and legal apparatus elites like Guo Shengkun (former public security vice minister, incumbent PLAC secretary), Fu Zhenghua (former public security vice minister, incumbent justice minister), and Huang Ming (former public security vice minister, incumbent minister of emergency management).

2. The highly irregular purge of Meng Hongwei comes just when the CCP is facing mounting pressure from the U.S. and the international community. For the face-conscious CCP to forsake international acceptance and legitimacy to carry out the unprecedented vanishing of an Interpol chief—especially after likely expanding much effort to secure his election—suggests that there is much more to the incident than routine Party rectification work.

In examining geopolitical developments, the timing of public appearances by retired Jiang faction officials, the reaction from the Ministry of Public Security, and state media commentaries, we believe that the CCP factional struggle has entered a critical period.

There is a possibility that Xi’s rivals had launched a “soft coup” against him. Unlike previous coup attempts by the Jiang faction where the aim was to ouster Xi, Xi’s rivals would more likely be seeking ways to curb his power, such as forcing him to revert to the collective leadership model, reimpose term limits in 2022, or halt the purge of Jiang faction officials. To achieve their objectives, Xi’s rivals would try to exploit his policy failures, starting with the Sino-U.S. trade war.

Geopolitical pressures

We analyzed back in June when President Donald Trump announced the first wave of tariffs that they represent a “major diplomatic defeat for Xi Jinping and a huge loss of face.” While “Xi may take the defeat in his stride,” the CCP’s political culture “dictates that he has to retaliate or face serious challenges to his rule from rivals and the system.” Our analysis has since been corroborated by subsequent developments: The PRC imposed retaliatory tariffs; Chinese scholars wrote oblique critiques of Xi’s rule; Xi’s lieutenants had to remind officials to uphold his “paramount authority” (“ding yu yi zun”); and rumors from the summer Beidaihe meeting hint at Party elder discontent with Xi’s leadership.

CCP factional infighting is a “life-and-death” struggle, and the various sides would mercilessly target opponent weak points when an opening becomes obvious. Such an opening emerged after Trump imposed a second wave of larger tariffs on Chinese imports; Western news outlets started reporting that the Chinese officials were suspecting that the trade war is just a part of Trump’s plan to pushback against the PRC. Then on Sept. 23, the American news website Axios reported that the Trump administration has “secret anti-China plans” that involve launching “a major,’administration-wide,’ broadside against China.” Days later, Trump called out the PRC’s unfair trade practices at the United Nations General Assembly and said that China was trying to interfere in the U.S. midterm election in November. A week later, Vice President Mike Pence gave a speech on China that was essentially a broadside against the CCP.

It is quite likely that the various CCP factions would have gotten wind that the Trump administration was going to publicly toughen America’s stance towards the PRC no later than the Sept. 23 Axios article mentioned above. Armed with new knowledge and “evidence,” Xi’s rivals would undoubtedly seek to exploit the worsening Sino-U.S. relations under Xi’s leadership to undermine him. Xi might have either anticipated danger or spotted a serious threat developing, and felt compelled to take drastic action to preserve his leadership. Thus, it is perhaps not purely coincidental that Grace Meng received a menacing text from Meng Hongwei on Sept. 25, or during a period where geopolitical pressure from the U.S. was visibly mounting.

The Jiang faction resurfaces

Around the period of Meng Hongwei’s arrest, several retired Jiang faction officials started appearing in public:

- On Sept. 27, a publication under the official Legal Evening Daily newspaper reported that Liu Yunshan, the former Politburo Standing Committee member and propaganda apparatus chief, had visited the Shaolin Temple in Henan Province and was received by the temple’s abbot. The article was subsequently deleted.

- On Oct. 5, Chinese writer Gao Falin posted two photos of former Chinese vice president Li Yuanchao and his wife visiting a farm in Jiangsu Province that they had worked on in the 1950s on his Twitter account. Gao deleted the photos after they got traction on social media.

- On Oct. 7, Wu Bangguo, a Politburo Standing Committee member of the 16th and 17th CCP Central Committee and former National People’s Congress chairman, made a public appearance at his ancestral home of Feidong County in Anhui Province. A video of his Feidong visit later circulated on Chinese social media.

Per CCP political custom, the public appearances of retired high-ranking officials usually go unreported. When reports of retired CCP elites going on walkabouts find their way into the news cycle, the phenomenon is more often than not an attempt by Party factions to signal political strength or rally support. In the context of Meng Hongwei’s arrest, the walkabouts by the retired Jiang faction officials could be intended to signal to opponents of Xi Jinping that the Jiang faction still has political power and that the resistance to Xi should continue.

We analyzed in January that Li Yuanchao could “enjoy a quiet retirement if he promises to stay out of factional politics” after stepping down at the Two Sessions. However, if “Li creates trouble for Xi, then he is in danger of being investigated on charges of corruption or political disloyalty.” Li Yuanchao presently faces high levels of political risk due to his Jiang faction connections, and his recent “public appearance” could be held against him depending on the state of the factional struggle.

Decoding official statements on Meng’s arrest

The statements put out by the discipline inspection commission and the public security ministry on Meng Hongwei’s arrest indicate that he was very likely involved in a “soft coup,” or some other serious political challenge, against the Xi leadership.

The CCDI statement on Meng’s investigation was only 26 characters long, but it was put out in about an hour after Grace Meng’s press conference on Oct. 7. One way of looking at the CCDI statement is that it is intended to hedge against Ms. Meng and the growing international scrutiny on Meng Hongwei.

Zhao Kezhi, the public security minister, convened a meeting of the Ministry of Public Security’s Party committee in the early hours of the morning on Oct. 8 to discuss the Meng Hongwei incident, an extraordinary event that is meant to demonstrate the seriousness of the investigation.

Meanwhile, the statement on meeting chaired by Zhao was peppered with Party parlance that implicates Meng in a coup plot:

- Meng’s arrest was tied with the need to clear out the “pernicious influence of Zhou Yongkang.” Observers note that Zhou had mobilized People’s Armed Police forces in a coup attempt after the 2012 Wang Lijun incident. (link)

- The second and third paragraphs in the statement emphasized the need for “absolute loyalty” to the “Xi core,” and their 533 characters took up a third of the entire statement. When juxtaposed with the Zhou Yongkang reference, the meaning is clear—the leadership has been challenged by public security officials connected with a known coup plotter, and the security apparatus must hence make known its fealty to the leader.

- The fifth paragraph calls for the establishment of a task force to probe those who “jointly accepted bribes” with Meng Hongwei. The task force is ordered to “resolutely implement the organization’s arrangement and not barter terms or negotiate ‘prices’ with the organization.” In parsing the Party speak, Zhao Kezhi is suggesting that Meng is not the only one involved in opposing the Xi leadership, and that there is a high probability that Meng’s associates are either current or former public security officials. There is also a hint that investigations into Meng Hongwei have met with resistance.

- The call to “strictly guard against the disruptive and subversive activities of hostile forces” in the second last paragraph of the statement is another way of indicating that the Meng Hongwei incident directly concerns the security of the CCP regime.

Decoding state commentary on ‘reform and opening up’

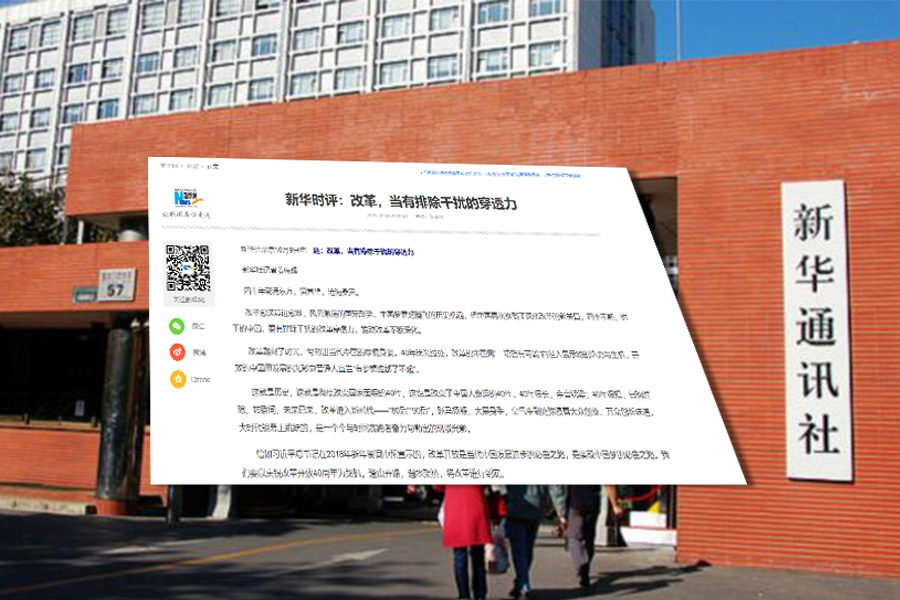

After the investigation into Meng Hongwei became official, state mouthpiece Xinhua ran several commentaries to discuss “reform and opening up” under Xi Jinping. In particular, the second piece in a two-part commentary spotlights resistance from interest groups and stress Xi’s determination to press ahead with reforms. The commentaries also use phrases and language commonly found in official essays published during Xi’s first term when the factional struggle between the Xi camp and the Jiang faction was particularly intense.

If our analysis that Xi is facing a “soft coup” is accurate, then the Xinhua commentaries are meant to put the political power behind Meng Hongwei on notice while sending a strong political signal to the rest of the regime.

On Oct. 8, Xinhua published “Unswervingly Carry Out Reform to the End—A Commentary on China’s Reform and Development (Part I).” The piece relies on a deluge of economic figures to back the point that “the outlook of the Chinese economy is optimistic,” and appears to have been prepared before the Meng Hongwei incident to make a “feel-good” statement.

The second part of the “Unswervingly Carry Out Reform to the End” commentary, published on Oct. 9, shifts to a somber, gritty tone. The commentary cites Xi Jinping’s call to “emancipate the mind … deepen reform, and resolve contradictions” during his recent inspection of Northeast China. Phrases like “emancipate the mind” are often trotted out when Party leaders are promoting structural reforms, while “deepen reform” and “resolve contradictions” hint at the need to eliminate interest groups that resist policies. The commentary also notes that Xi’s reforms must go on despite difficulties, and repeats some phrases that allude to the Xi-Jiang clash during Xi’s first term (“pauses and retreats are not solutions, and reform must reach its end”; “as reform enters deep-water territory, every step forward is a challenge”; “[we] must bite down on bone”). Further, the Oct. 9 commentary notes that there is a need to “say goodbye to ‘nine dragons controlling the waters’” with structural reform in the section of the commentary calling for “determined reformed as the solution to resolving difficult problems.” The Chinese saying “nine dragons controlling the waters,” or “jiu long zhi shui,” is an allusion to the collective leadership system, and in specific cases, the 9-member Politburo Standing Committee that Jiang Zemin imposed on Hu Jintao.

When taken in context of the Meng Hongwei investigation, the Oct. 9 Xinhua commentary seems to be hinting that there is internal resistance to Xi’s policies from a familiar political power, and the CCP regime must oppose the resistors and rally behind Xi’s reform movement.

Another commentary piece published on Oct. 9, “Xinhua Commentary: To Carry Out Reform, Having Sufficient Penetrative Power to Eliminate Interference is Vital,” appears to reinforce the themes mentioned in the second part of “Unswervingly Carry Out Reform to the End.” Some lines are worth a brief unpacking:

- “As reform enters a critical period and deep-water territory, there is an even greater need to bite down on bone, deal with more complex interests, and expand the scope” — “Critical period” alludes to troubled times and “deep-water territory” suggests that Beijing is planning to tackle potential threats. “Complex interests” and “expand the scope” hint at rival interest groups. The commentary is indicating that the Xi leadership will “bite down on bone,” or take tough action, to resolve the obstructions to reform.

- “How to advance reform by innovating the system” — This is a call to reorganize the Jiang-era system through structural reform.

- “How to courageously implement reform efforts to penetrate the surface and reach the bottom of contradictions” — The Xi leadership is suggesting that it is willing to take bold action to quell opposition to reform policies.

- “No matter how complicated the world and domestic situation seem, the reform wave will only advance! advance! advance!” — Neither U.S. and international pressure nor CCP factional fighting will affect Xi Jinping’s decision to push through reform.

In sum, the Xi leadership is signaling to the regime with the Xinhua commentaries that officials should fall in line behind Xi and implement his policies well to weather the Sino-U.S. trade war and other geopolitical pressures. Resist, and Beijing will be merciless in the purge, as evidenced by the investigation of Meng Hongwei.

What’s next:

1. Meng Hongwei’s text messages to his wife, Grace Meng’s subsequent actions, and the death threats she received suggest that the former Interpol chief might have had a contingency plan ready in the event of his arrest. However, Meng might have overestimated his odds about returning to China.

We believe that there is a chance that Meng left classified information with his family to ease their asylum application in France and guarantee their safety from would-be assailants, as well as ensure that the CCP would not deal with him too harshly and provoke a greater scandal for the regime. In other words, there might be a “Mexican standoff” at play whose outcome could hinge on how the CCP chooses to handle Meng’s investigation.

2. Meng would almost certainly sell out his associates in self-preservation. And Beijing will likely use the evidence gathered from the investigation into Meng Hongwei to arrest another batch of high-ranking officials. Officials in the current Politburo and retired Politburo Standing Committee members, particularly those with domestic security apparatus and Jiang faction backgrounds, are at high risk of being purged.

3. By escalating his campaign to eliminate the resistance, Xi Jinping risks alienating a broad and influential collection of Party elites and their interest groups. The Jiang faction could potentially rally the groups disenfranchised by Xi’s policies to form an “anti-Xi coalition” of sorts to challenge his leadership. However, we have yet to see evidence of an “anti-Xi coalition,” and the chances of its formation under Xi’s ever-tightening grip over the regime seem remote.

4. Based on our understanding of the CCP and Party culture, we believe that Xi, like the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, will be ultimately unsuccessful in reforming the communist regime. Xi, like Gorbachev, seems determined to give reform a try, and we might yet see developments that read like success for Xi.

But the heavy-handed arrest of Meng Hongwei proves that Xi cannot avoid CCP tactics even as he touts reform. With international sentiment turning against the PRC, escalating internal tensions caused by the factional struggle, and the CCP system itself serving as shackles, Xi’s reform effort is doomed to failure—unless he can break free from these constraints.

Xi Jinping presently faces very high levels of political risk, and political pressures on him will only increase going forward.

Get smart:

CCP elite politics and factional struggles may be confusing and complicated, but they play an outsized role in shaping China’s future. And SinoInsider has a track record of correctly forecasting personnel movements and analyzing key developments in elite CCP politics.

Businesses and investors in China looking to lower risks and uncover opportunities can contact us today.