◎ The People’s Armed Police reforms lack the flash of Xi’s more eye-catching moves to consolidate control.

By Janet Liu and Larry Ong

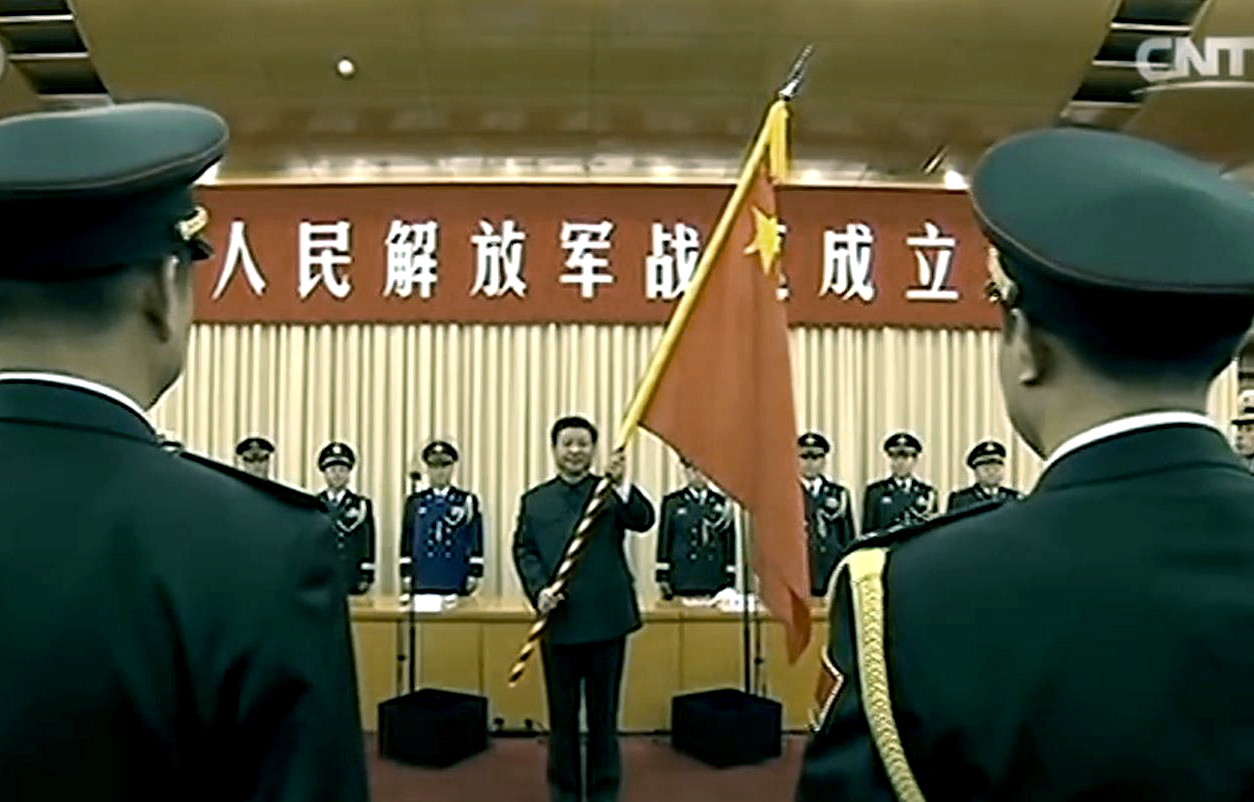

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s power consolidation at the 19th Party Congress and the scrapping of presidential term limits at the Two Sessions were the recent focus of international scrutiny. In the same period, two reforms to the People’s Armed Police (PAP) were passed without much fanfare. On Jan. 1, the PAP came under the sole control of the Central Military Commission (CMC); previously, the CMC and the State Council directed the PAP in a dual command structure. On March 21, the State Council withdrew civilian-oriented, firefighting and frontier defense troops from the PAP, and placed the withdrawn PAP units under local public security and emergency response regulators.

The PAP reforms lack the flash of Xi’s more eye-catching moves to consolidate control. But the reforms are no less vital to Xi’s power consolidation as they serve very practical purposes and have potentially far-reaching effects. The reforms cap Xi’s five-year effort to wrestle the paramilitary away from his political rivals and safeguard his leadership against future coup attempts. And Xi’s effort to clean out and restructure the PAP is a means to ensure that his orders, unlike Hu Jintao’s, would be properly implemented by the Chinese officialdom.

Coup tool

The modern PAP was established in 1982 to perform domestic security work (civilian policing, firefighting, border defense, protection of key individuals and installations, counterterrorism) in peacetime and support the military as light infantry in war. Until recently, the PAP came under a CMC-State Council duel command structure, an arrangement that allowed local government officials to mobilize the paramilitary for local “stability maintenance” operations.

The PAP was strengthened significantly under the watch of Jiang Zemin, the former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader. In 1995, the PAP headquarters was elevated to military region status while provincial commands were upgraded to the sub-military region grade. In 1996, 14 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) divisions were transferred to the PAP to serve as mechanized units, swelling the PAP ranks and fighting capabilities. The PAP eventually grew to an estimated 1.5 million troops in the 2000s, and many of Jiang’s supporters were elevated to key leadership positions. Jiang bolstered the PAP to gain troop loyalty and secure a foothold in consolidating his control over the military at large. The PAP reforms also allowed Jiang, who had no military experience before becoming CMC chairman, come into his own against entrenched military interest groups.

During his era of dominance, Jiang and his political faction frequently turned to the PAP to carry out repressive “stability maintenance” work. Under purged security czar Zhou Yongkang, the PAP cracked down on rights activists, religious groups, and ethnic minorities identified as “security threats” around the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics period. PAP troops also brutally squashed protests in Tibet (2008) and Xinjiang (2009). Meanwhile, international investigators found that PAP hospitals are sites of forced organ harvesting of prisoners of conscience.

The Jiang faction would utilize the PAP for shadier operations following the Wang Lijun incident in 2012. When Wang, formerly Chongqing’s top cop, fled to the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu, Chongqing boss and Jiang lieutenant Bo Xilai dispatched his PAP troops to surround the consulate. Wang’s defection and Bo’s actions sparked a huge scandal, and Bo was removed from his post on March 15. Four days later, Zhou Yongkang mobilized PAP troops and encircled Zhongnanhai, the CCP headquarters in Beijing, according to several media accounts. Hu Jintao, then Chinese leader, reportedly brought in nearby PLA forces to thwart the Jiang faction coup attempt.

The Xi administration has since publicly alluded to the Jiang faction coup on numerous occasions. In a book of speeches published in 2016, Xi Jinping named Bo Xilai, Zhou Yongkang, and others as conspirators in a plot to “wreck and split the Party.” At the 19th Party Congress, Xi was seen on television shaking hands and exchanging words with Hu Jintao as he was returning to his seat after delivering a marathon speech. A TV host from Taiwan’s Eastern Broadcasting Company commented that Xi was thanking Hu for joining forces with him to “resist Jiang Zemin’s influence, and the plot to usurp the leadership.” Also at the 19th Congress, securities regulator Liu Shiyu criticized Bo, Zhou, and others of having “plotted to usurp the Party leadership,” Hong Kong media reported. Politburo member Ding Xuexiang later echoed Liu’s comments about leadership usurpation at a work meeting for departments directly subordinate to the CCP on Jan. 26.

Purge and reorganization

The Jiang faction’s use of the PAP as a coup tool likely determined the scale of the paramilitary shakeup during Xi Jinping’s first term.

The PAP’s top ranks have been reshuffled thoroughly since 2012. To date, Guizhou PAP political commissar Han Yunpeng is the only senior armed police provincial official out of 62 who took office before the 18th Party Congress who is still serving. Nearly half of the 61 posts changed hands twice from 2012 to 2017. One of the biggest reshuffles occurred in June 2017 when 15 senior PAP officials (10 commanders and five commissars) in 14 provinces were replaced. The incoming personnel were either promoted from the ranks or brought in from other regions or military units.

Another change that came with security personnel reshuffling was the appointment of provincial PLAC secretaries who held offices other than public security bureau chief. This move appears to be designed to prevent the Party government hierarchy from interfering with the state hierarchy through domestic security officials holding multiple appointments. For instance, Zhou Yongkang wielded immense power as central PLAC chief (2007 to 2012) as he could mobilize PAP troops through provincial PLAC secretaries. Provincial PLAC secretaries could direct PAP forces because they were usually public security chiefs, and public security chiefs customarily hold the office of provincial PAP first commissar.

The PAP personnel reshuffle has also seen Xi’s foes removed and friendlies promoted. At least 12 high-ranking PAP officials have been purged since Xi Jinping took office, including former PAP commander Wang Jianping and his deputy Niu Zhizhong. Wang Jianping is a close associate of Zhou Yongkang, and is reportedly involved in Zhou’s coup plot. His replacement, Wang Ning (no relation to Wang Jianping), was air defense commander and 91st Division chief of the 31st Group Army (now 73rd Group Army) in Fujian when Xi was Fujian governor. Wang Ning’s deputy, Qin Tian, is the son of former defense minister Qin Jiwei. The elder Qin was a close ally of Deng Xiaoping and was known for having deep enmity for Jiang Zemin.

Changes to the PAP were not limited to elite personnel. In 2016, the CMC announced that the PAP was would shutter its for-profit ventures, including hospital medical services, by 2018. According to a March 2017 report by the pro-Beijing Hong Kong news site Phoenix Television, the PAP was to cut 36,000 cadres, including 400 cadres from each corp and 1,200 cadres from the Beijing corps, by 2018. Also, the division commands in the leading Beijing and Xinjiang corps would be scrapped as units downsize from division-level to detachment-level. The Phoenix report added that the PAP’s 14 mobile divisions would also be trimmed to just four. The changes, when actualized, would effectively roll back the Jiang era PAP policies.

The 2018 PAP reforms consolidate the gains of the sweeping personnel changes. Switching from a duel command structure to having only the CMC direct the PAP gives Xi Jinping, the CMC chairman, greater control over the paramilitary. Removing State Council control over the PAP also virtually eliminates another Bo Xilai or Zhou Yongkang situation as CCP elites cannot legally mobilize local paramilitary units to serve their own interests. Meanwhile, the withdrawal of civilian-oriented, firefighting, emergency response, and frontier defense troops from the PAP seems to be aimed at further restricting its jurisdiction, resolving gray command areas, and creating clear lines of duty. The post-reform PAP would more closely resemble a military entity, and not the messy but powerful military-public security-emergency response hybrid. The outcome of the PAP streamlining is that it no longer has the potential to be abused by ambitious Chinese officials to strengthen their authority and launch coups against the central leadership.

Advancing reform

Aside from eliminating coup threats, Xi Jinping’s PAP reforms appear to be part of his ongoing effort to ensure that his orders go beyond the gates of Zhongnanhai, a problem which plagued Hu Jintao’s entire tenure as Chinese leader. Hu’s inability to control the Chinese officialdom and the military is perhaps best seen in a 2011 incident where he expressed shock at the conducting of a Chinese stealth fighter test during then U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates visit to Beijing when Gates informed him of it. Bureaucratic “passive resistance” is also why the Xi administration was unable to carry out many of the reforms it announced at the third plenary session in 2013.

The March 2018 PAP restructuring gives Chinese officials a practical reason to stop resisting and fall in line with Xi. Earlier, the PAP was responsible for providing armed security for key individuals like senior officials at the provincial-level and above, installations, and major activities. Under the old arrangement where provincial PLAC secretaries typically wore two additional security hats (head of public security and armed police first commissar), it meant that the PLAC chief was the de facto overseer of senior officials’ personal protection. With the PLAC in the Jiang faction’s hands, officials had little incentive to be supportive of the Xi administration and carry out orders from the central government to the best of their ability. After Xi’s PAP reforms and continued marginalization of the PLAC, however, the public security minister is now effectively in charge of the armed security details for key personnel. And since the current public security chief Zhao Kezhi is Xi’s ally, Xi, and not the Jiang faction, has become the de facto guarantor of personal security for leading Chinese officials. In other words, Chinese officials have a vested interest in executing orders from Zhongnanhai well—or else.

A sign that Xi has made progress with the officialdom resistance problem can be seen from efforts to establish a free-trade zone in his first and second term. Plans for the Shanghai free-trade zone in 2013 were vague and underwent numerous revisions as local officials found ways to roadblock Chinese premier Li Keqiang, who oversaw the project. Li was reportedly so furious with the outcome of the reform that he pounded his desk and boycotted the opening of the Shanghai free-trade zone. In contrast, the 2018 plans for the Hainan free-trade port were detailed and included specific work project timelines. Already, one of the first initiatives, allowing travelers from 59 countries to visit Hainan without a visa, was smoothly implemented by its May 1 deadline.

Conclusion

Xi Jinping’s PAP reforms, like the anti-corruption campaign and military modernization measures, are partly aimed at power consolidation and eliminating avenues by which political rivals can upend his rule. The reforms also help Xi to resolve the problem of getting the Chinese officialdom to follow through on his orders and avoid his tenure becoming a repeat of Hu Jintao’s “lost decade.” The reforms, however, do not guarantee safety or success for Xi as loyalists of rival factions and other interest groups are still at large.