◎ The following analysis was first published in the May 13, 2021 edition of our subscriber-only SinoWeekly Plus newsletter. Subscribe to SinoInsider to view past analyses in our newsletter archive.

On May 11, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released the PRC’s Seventh National Population Census. The latest census showed that China’s population increased 5.38 percent (72.06 million) from 2010, when the last census was taken, to 1.41178 billion. The annual population growth rate of 0.53 percent between 2010 and 2020 was 0.04 percentage points lower than the 0.57 percent between 2000 to 2010. The census noted that the “population of China maintained a mild growth momentum in the past decade.”

During a press conference to announce the census, NBS director Ning Jizhe said that China recorded 12 million births in 2020 for a fertility rate of 1.3.

In juxtaposing the Seventh National Population Census and the Sixth National Population Census, 25 out of 31 provinces saw increased populations in the past decade. The five provinces that saw the most growth were Guangdong (up 21,709,378), Zhejiang (up 10,140,697), Jiangsu (up 6,088,113), Shandong (up 5,734,388) and Henan (up 5,341,952). The figures indicate a shift in population to the wealthy provinces on the southeastern coast of China.

Comparisons between the sixth and seventh census also reveal a shrinking workforce and aging population. Those in the 0-14 age bracket (253,383,938 persons, or 17.95 percent of the total population) grew by only 1.35 percent; the 15-59 age bracket shrunk 6.79 percent (894,376,020 persons, 63.35 percent); those 60 and above (264,018,766 persons, 18.70 percent) increased by 5.44 percent; and the 65 and older bracket (190,635,280 persons, 13.50 percent) grew by 4.63 percent.

The proportion of the 65-and-older population to the total population in all provinces exceeded the aging population (高齡化社會) boundary of 7 percent, with the exception of Tibet, where people above the age of 65 made up 5.67 percent of the region’s population. Twelve of China’s 31 provinces (representing 624 million people, or 44.2 percent of China’s population) have 65-and-older population sizes that correspond with the “aged population” definition (14 to 20 percent). Guangdong, the most populous province, has the smallest aged population proportionally speaking (8.58 percent), and the largest proportion of people of workforce age (68.8 percent).

***

The Seventh National Population Census was originally scheduled for release in “early April,” and is usually issued no later than between April 10 to April 15. However, the CCP said that the release of the 2020 census data would be postponed after the usual release period had passed, but did not give a date at the time. On April 27, the Financial Times reported that the census data was expected to show that China’s population fell below 1.4 billion, the first decline since the Great Leap Forward famine. Meanwhile, many observers believe that China’s population has indeed declined and the CCP will not release detailed census data until the various government departments reach a consensus on the data and its impact.

Data from the Ministry of Public Security Household Administration Research Center’s “2020 National Name Report” (2020年全国姓名报告) released on Feb. 8 seemed to affirm suspicions of China’s population decline. According to the report, 10.035 million newborns were registered in the PRC’s household registration system (hukou) in 2020, down 1.755 million from 11.79 million in 2019 and a record low since the establishment of the PRC in 1949. Going by the 80.48 percent registration rate for newborns in 2019, it is possible that there were as many as 2.18 million fewer newborns in 2020 (12.47 million) as compared to 2019 (14.65 million). The 2.18 million figure also means that the number of newborns fell to 8.9 percent in 2020, or lower than the 10 to 14 percent range of the past two decades. Newborn registration figures from the “2020 National Name Report” also meant that China’s birth rate had been declining for four consecutive years; the CCP’s “comprehensive two-child” policy implemented in 2015 only produced a brief “spike” in 2016.

On April 29, the NBS issued a one-sentence statement claiming that China’s population grew in 2020 and specific data would be released in the census. On May 8, the Bureau announced a press conference to launch the Seventh National Population Census on May 11.

***

In promoting the Seventh National Population Census, the CCP said that the collection of data was “done completely electronically,” and “departmental administration records” were also used in Big Data analysis. The CCP also said that its census data collection period was between November and December 2020. Given the use of advanced technology and comprehensive data stores, the 2020 census report should technically be more accurate and released more rapidly than previous editions.

OUR TAKE

1. The CCP needs to constantly project itself and its brutal authoritarian model as “great, glorious, correct” (偉光正) to survive and dominate. Externally, staying “great, glorious, correct” at all times allows the Party to tout its so-called “China Model” as a “superior” system that other countries should follow. Domestically, being “great, glorious, correct” helps the Party iron out its political legitimacy issues to a degree. In practice, this means China has to have positive GDP growth during a pandemic, and come across as the only major country with “economic growth and energy.”

The CCP knows that showing fallibility is weakness and the first step towards demise. But “weakness” is also relative. In revisiting the GDP example, it is acceptable for China to have 2.3 percent growth in 2020 (lower than the 6 percent-plus growth of recent years) if the U.S. is seeing a 3.5 percent year-on-year GDP contraction. And with birth rates and populations declining worldwide, China showing any sort of population increase in its latest census counts as an “achievement” for the CCP.

The most likely reason why the CCP held out on releasing its 2020 census data is the very real possibility that China’s population actually shrunk by a troubling amount over the past decade and especially in 2020. And if the census showed that China’s population fell below 1.4 billion as reported by the Financial Times, then the CCP needs to “airbrush” the final figures so that the regime can still come across as “great, glorious, correct.” Declining demographics is a serious weakness for the CCP because:

- It represents a failure of the CCP’s policies and “authoritarian advantage,” especially its recent pro-natalist measures and social welfare schemes. Domestic policy failures ultimately undermine the “China Model” and the Party’s “unblemished” image.

- A declining population means a shrinking workforce, greater challenges associated with an aging society, smaller markets, and less national vitality. Again, this represents a failure of the “China Model” and the CCP.

- Worse, a serious diminishing of China’s population in the context of a pandemic hints at overwhelming deaths and extensive cover-up (fraudulent official data) on the CCP’s part. This disintegrates the CCP’s narrative of having “controlled” COVID-19, exposes the regime as being woefully corrupt and incompetent, and leaves the PRC vulnerable to calls for accountability by the international community.

“Airbrushing” the final census data, however, is no mean feat. Party Central will likely have to come up with an “acceptable” number that does not look too fishy when presented to the public but allows the CCP to stay “great, glorious, correct” at home and abroad. The official figure—just a hair over 1.4 billion at 1.41178 billion—is certainly “acceptable” enough.

Manipulating data collected and controlled by the NBS to fit the required “reality” would be the least challenging part. More challenging is “convincing” other central departments and local governments to “massage” their figures in just the “right” way. Per Party culture (“prefer left rather than right,” “ends justify the means,” deceptiveness, struggle, etc.), officials looking to minimize their political risks, preserve career security, and safeguard local or factional interests are inclined to manipulate their data in a fashion that benefits themselves. Thus, Beijing likely needed the months between the completion of data collection in late 2020 until early May to properly “unify” the PRC’s final census data before release.

2. The CCP has a long history of population data manipulation and falsification, while the population issue itself is tied with various local and departmental interests.

Family planning became regime policy in the PRC starting from the early 1980s. The National Family Planning Commission (now National Population and Family Planning Commission) was established in 1981 as a cabinet-level executive department under the State Council, with a PRC vice premier serving as the Commission’s director.

The fact that family planning was prioritized meant two things. First, subsequent CCP leaderships would find it immensely difficult to undo the policy because it is tied with the political legacy of paramount leader and regime “architect” Deng Xiaoping. Second, family planning would become a permanent part of performance evaluation for PRC officials. This meant that officials were incentivized to implement draconian measures (forced sterilization and abortions, heavy fines, hukou registration restrictions, etc.) to show “results” in the one-child policy and secure promotion. Family planning violation fines became a steady source of government revenue in parts of China, while some local governments even “confiscated” newborns from parents who could not afford fines; “confiscated” babies would be designated as “abandoned children” and “resold” on the black market or to orphanages for a profit.

Over time, central and local family planning departments and associated government organs formed chains of interests. To preserve those interests, the aforementioned groups had to keep the one-child policy on the books indefinitely. This meant engaging in data manipulation and falsification, as well as other malpractices.

Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of a 2007 book (“Big Country With an Empty Nest”) that criticized the CCP’s family planning policy, noted in various articles and media interviews that the PRC has been “cooking the books” (灌水) with its population data since the early 1990s. Yi said that his research into China’s population issues found that the National Family Planning Commission (later incorporated into the National Health Commission), the NBS, as well as local education bureaus and public security bureaus all exaggerated their population data for different reasons to secure their respective interests. For instance, the National Family Planning Commission needed to show higher fertility rates to keep the one-child policy “relevant”; the NBS deputy director who was in charge of the census followed the leadership of the National Family Planning Commission; local education bureaus obtained more central government funding by over-reporting student counts; and local public security bureaus released unreliable data because they sometimes issued multiple hukou booklets to individuals who were looking to buy property and get more than one bite of the pie in accessing government services like healthcare and education.

Yi Fuxian found clear discrepancies when sieving through government data. In 1990, the official fertility rate in China was 2.25 births per woman, but a sample survey in 1991 noted that the fertility rate was only 1.8. A small census in 1995 found that the fertility rate was 1.43, while another census in 2000 noted a drop to 1.22 births per woman. However, the official fertility rate in 2000 was 2.1 percent, which reflected only a modest drop from 1990, rather than a sharp decline. In 2000, the census recorded the number of births at more than 14 million, but the National Family Planning Commission and the NBS announced that it was 17.71 million. Ten years later, the 2010 census showed the number of 10-year-olds at over 14 million, which was consistent with the number of newborns recorded in the 2000 census.

Yi Fuxian said, “The biggest problem with China’s census data is not numbers being fudged in the original data, but the adjustments in the final data. The original data is lower than expected, and the authorities have to make a sharp turn.” Yi also noted in 2007 that estimations of China’s future development and economic prospects are too optimistic because an assessment of various social indicators like healthcare, education, marriages, etc. suggested that China’s population in 2020 would not exceed 1.28 billion. That year, National Population and Family Planning Commission senior official Yu Xuejun said in an interview with a PRC government website that China’s total fertility rate “is definitely not 1.2 [births per woman]. If it was 1.2, we wouldn’t need to implement family planning. Because the fertility rate is still 1.7 to 1.8, we still need family planning.”

In commenting on the PRC’s 2020 census birth data, Yi told The Wall Street Journal, “What’s disastrous for China’s economy behind the data is a fundamental demographic shift.”

To sum up the information above, Party Central institutes family planning, and the CCP officialdom forms chains of interests in accordance with the regime’s political culture. The various interest groups then prop up the family planning policy by all means necessary to protect their interests. This in turn means that Beijing would receive faulty data and be slow to alter the policy until irreversible damage had been done.

By the time of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, the shortcomings of the one-child policy (gender imbalance, disappearance of demographic dividend, aging society, etc.) would have already surfaced and cannot be easily obscured by fraudulent data. But Hu and Wen would not have been able to reverse the CCP’s family planning policy even if they wanted to. For one, they lacked “quan wei” to push through reforms and take on the many powerful factional and local interest groups benefiting from the one-child policy. Hu and Wen would also be challenging Deng Xiaoping’s political legacy and upsetting the CCP’s decades-long “great, glorious, correct” family planning narrative. So the can was kicked down the road until Xi Jinping consolidated his authority over the military in 2015 and rolled out a “two-child” policy in January 2016. Xi also dissolved the National Population and Family Planning Commission as part of Party and state institutional reforms in 2018 and created the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

Changing the regime’s family planning policy, however, comes with political risks for Xi. First, Xi is basically admitting that the CCP has been wrong with its one-child policy for some time and disrupting the “great, glorious, correct” family planning narrative. Second, Xi has made family planning tougher for the various interest groups benefiting from it (pro-natalist policies are harder to achieve than anti-natalist ones), and earned himself yet more enemies. Finally, Xi “owns” his family planning reforms and will bear the blame if they fail; his predecessors had an easier time in placing the responsibility of the one-child policy at the feet of Deng.

Worse, Xi’s family planning reforms appear “too little, too late” at this point. Countries like Singapore that implemented successful anti-natalist policies continue to struggle with declining fertility rates years after reversing course, and the PRC is currently encountering the same dilemma. Moreover, the PRC government has very likely been crafting policies using badly skewed or outright falsified population data for decades, with consequential ramifications for the long-term planning of the economy, society, defense, foreign affairs, and education.

3. The CCP may have “succeeded” in producing “population growth” in its Seventh National Population Census to preserve its “great, glorious, correct” image, but its manipulation of the final outcome leaves other troubling data discrepancies:

a) Unusual birth and death rates

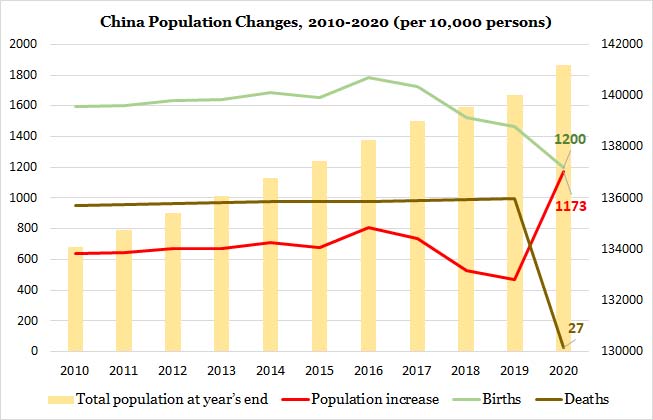

- China’s total population in 2019 was 1.40005 billion, and 1.41178 billion in 2020. That means officially, China’s population grew by 11.73 million year-on-year. However, if we go by the 12 million births figure provided by NBS director Ning Jizhe, then China only saw 270,000 deaths in 2020—an impossible amount given the 9.98 million official deaths in 2019.

- Another way to estimate birth figures for 2020 is taking the difference in the ages 0-14 population in 2019 (234.92 million) and 2020 (253.38 million). Subtracting the official population growth figure (11.73 million) from the difference in 2019 and 2020 ages 0-14 population (18.46 million) gives a 2020 death figure of 6.73 million, a 32.6 percent decrease from 2019. However, this estimated death figure is still suspect given the coronavirus pandemic that spread throughout China and was subject to heavy cover-up by the CCP.

- A third method of estimating the 2020 birth figure is to subtract cumulative births from 2006 to 2019 (227.38 million) from the ages 0-14 population figure in 2020 (253.38 million). The 26 million births this method produces is significantly greater than the official 12 million, and results in 14.27 million deaths in 2020, or an increase of 43 percent from 2019.

Table 1 shows how abnormal the 2020 population growth and death figures are when compared with figures over the past decade. The 2020 figures are even more suspect in considering the COVID pandemic that year and unusually low official coronavirus death numbers.

b) Unusual ages 65-and-older

- Per official data, China’s age 65-and-older population increased by 14.6 million in 2020 (190.63 million) from 2019 (176.03 million). This figure implies that 14.6 million people born in 1955, or over 70 percent of those born in that year (20.4 million), were alive in 2020—a barely believable survival rate for a generation that experienced the Great Leap Forward famine, the Cultural Revolution, and other perils, which had a cumulative death toll in the tens of millions.

As seen from Table 2, the sharp spike in the ages 65-and-older population in 2020 is very suspicious, especially when compared with growth rates in the three years before. As we noted earlier, those born in 1955 are old enough to be mortally challenged by terrible political campaigns, natural and man-made disasters, and epidemics. Birth rates in 1955 are also the lowest on record between the years 1952 (corresponding to 2017) to 1955 (corresponding to 2020). So it is inconceivable that more than 5 million people joined the ages 65-and-older population in 2020 as compared to each of the previous three years. The 2020 spike also indicates that few people in the 65-and-older bracket died that year, which is hard to fathom when the elderly are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

4. A key reason why the CCP had to delay its census release could be that the regime had to find ways to paper over an apparent discrepancy between the actual number of COVID-19 victims and the extremely tiny official tally of COVID deaths (4,636 people nationwide, including 4,512 in Hubei Province, the epicenter of the pandemic, as of May 12).

We previously looked at how the CCP sought to cover up the COVID epidemic in China and how indirect indicators offer clues about the actual scale of coronavirus deaths (see here, here, here, and here). The sudden plunge in cell phone users on the mainland in January and February 2020 (down 21.073 million), as well as in November and December 2020 (down 6.789 million), are very suspicious, and it is reasonable to infer that the phenomenon is related to COVID deaths.

From Table 4, we can see a sharp drop in cellphone users in January and February 2020, followed by an increase of 10.605 million users in March. Some have argued that the January-February plunge is related to people with multiple phone lines canceling some to save costs. However, the argument is not entirely valid seeing how the CCP said it had “basically controlled” the epidemic at the end of February and was starting to ease people back into work. People with many phone lines are also unlikely to drop some with lockdowns lasting for a little over a month in some cities. Indeed, the spike in cellphone users in March reflects the relaxation of lockdown measures and people needing a cellphone to comply with health code requirements for work, travel, and school. Meanwhile, the sudden drop in cellphone users in November and December 2020 coincided with cities entering “wartime conditions” and areas classified as “high-risk.”

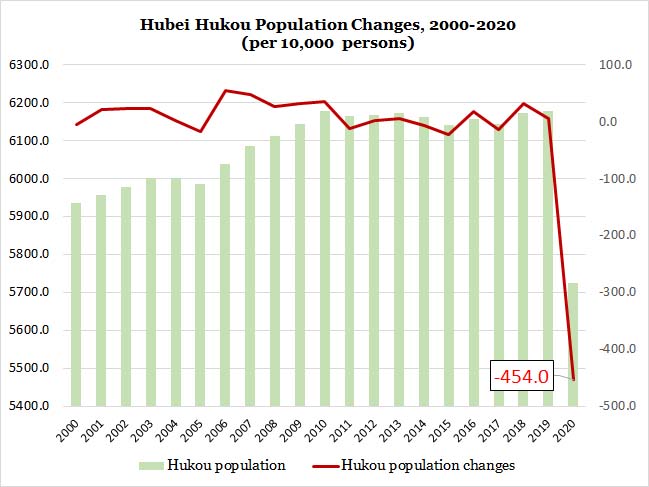

From Table 5, we can see that hukou registrations in Hubei plunged by 4.54 million in 2020. In contrast, Hubei’s hukou registrations stayed in the 61.38 million to 61.78 million range (fluctuation of less than 400,000) in the previous nine years (2011 to 2019). Hubei’s official figures suggest that the province’s population (births, deaths, migration, etc.) remained steady until last year when the epidemic broke out in Wuhan. The plunge in Hubei hukou registrations translates into hukou cancellations in the millions in 2020; hukou cancellations are the result of domestic and international migration, or death. While Wuhan typically sees greater migration as the city is a transportation and industrial hub, migration is an unlikely reason for mass hukou cancellations due to COVID lockdowns and other restrictions affecting domestic migration.

From the various data presented above, we have reason to believe that actual COVID deaths in China far exceed the official figure of 4,636; deaths caused by or related to complications of COVID-19 in 2020 could potentially be in the eight-digit range. Also, given our pandemic death estimate and in accounting for CCP’s data manipulation, we believe that China’s population currently stands at less than 1.4 billion.

4. The CCP faces a serious demographic and propaganda dilemma. On the one hand, Xi Jinping and the CCP are painfully aware of China’s population crisis and the dire need for family planning reform. On the other hand, the CCP cannot properly acknowledge China’s demographic disaster without shredding its “great, glorious, correct” image, exposing problems with China’s real estate bubble and Xi’s “dual circulation” policy, and ending the myth of the “China Model” and “authoritarian advantage.”

Beijing’s fraudulent population data problem also seriously affects its various policy and resource allocation plans. On the current trajectory, Communist China will find that it has no credibility in making the propaganda claim that it will surpass the United States by 2030.