◎ Bank trouble in China could in turn worsen social and economic instability in China to the detriment of Xi Jinping and the CCP.

Thousands of depositors across China have been gathering outside rural banks in Henan Province and demanding their money on a regular basis since their funds at four local rural banks were frozen in mid-April. About 400,000 depositors are estimated to be affected, according to mainland media.

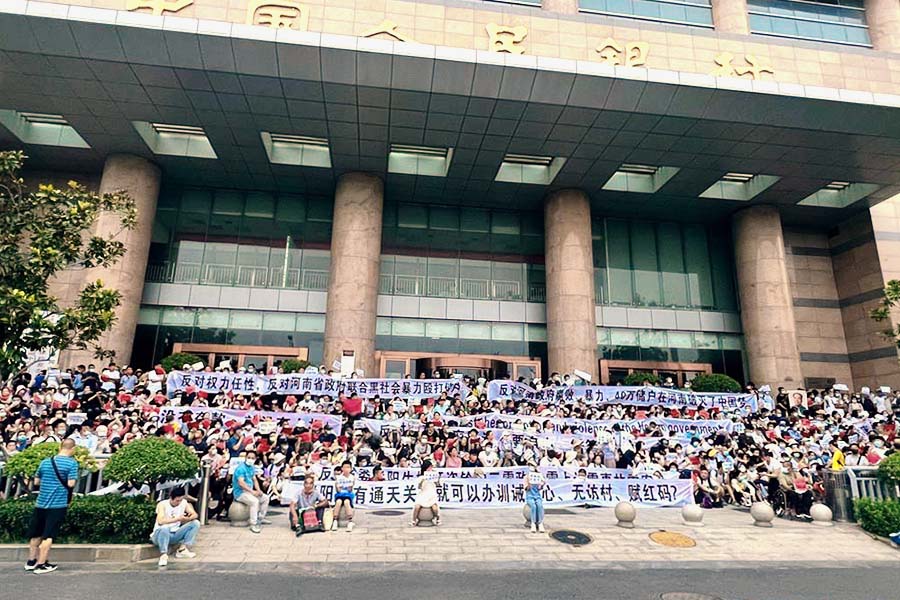

On July 10, a large demonstration outside the Zhengzhou City branch of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) was forcibly broken up by the local police and plainclothes security agents clad in white T-shirts. Videos of the heavy-handed police action were shared on Chinese social media and garnered tens of millions of views.

Henan was not the only place seeing bank trouble. On June 30, the market value of Bank of Nanjing’s stocks evaporated by over 7.4 billion yuan after the bank suddenly announced a day before that its director and president Lin Jingran had been “reappointed” to another position—vice chairman of a Nanjing state-owned company with total assets about 10 percent of what the Bank of Nanjing has—“due to work necessities.” The Bank of Nanjing’s release of a positive-looking semi-annual performance report on July 3 did not stop its shares from sliding another 1.07 percent to 10.18 yuan per share—down 15 percent from a peak in April—when the markets closed on July 4.

The recent bank trouble in China is a sign of systemic risks being triggered as the Chinese economy deteriorates rapidly and financial contagion from the real estate debt crisis spreads further. The bank trouble could in turn worsen social and economic instability in China to the detriment of General Secretary Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Blame game

The CCP authorities sought to blame the spreading of “malicious rumors” for the sharp sell-off of Bank of Nanjing stocks. On the evening of June 30, an industry analyst noted in a WeChat group chat that the bank is facing a debt crisis because it had been helping the local government with debt problems. The analyst added that the bank’s public sector loans went mainly to real estate developers and government projects, and that the bank may have to declare bankruptcy if its debt crisis is triggered.

Those “malicious rumors” about the Bank of Nanjing, however, are unlikely to have been the trigger for the June 30 sell-off because they were made only after the markets had closed. The markets also remained pessimistic even after the bank released a positive semi-annual performance report.

Meanwhile, the CCP authorities blamed fraudsters for the trouble with the four rural banks in Henan. In April, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) accused Henan New Fortune Group, a shareholder in the four banks, of using third-party internet platforms and fund brokers to illegally attract depositors from all over the country.

On July 11, the public security authorities of Xuchang City in Henan announced that they are investigating a “criminal gang” headed by Lü Yi and have made some arrests. Lü’s “criminal gang” is alleged to have used Henan New Fortune Group to control the troubled rural banks, created fictitious loans to illegally transfer funds, and established online platforms to promote financial products and seek out new customers.

Risks triggered

Lü Yi and his “criminal gang” may indeed be the main reason for rural bank troubles in Henan. However, problems with banks in Henan and Nanjing are likely only surfacing now because the economic situation in China has worsened to a point where risky or fraudulent schemes can no longer be sustained.

Rural banks like those in Henan previously took advantage of the CCP’s promotion of the “internet economy” starting in 2015 and used third-party platforms to sell high-yield deposit products to depositors from all over the country. This scheme saw the funds of rural banks swell beyond what banks of their size are capable of managing, sharply raising their risk profile. Those risks, however, stayed hidden during the real estate sector boom when developers readily took out bank loans and were able to pay interest.

In 2021, the PBoC noted in its financial stability report that 89 banks had taken in 550 billion yuan in deposits through third-party platforms. Close to half of the 550 billion yuan were held in banks rated as “high-risk” by the central bank. This troubling development was likely a key reason behind the CCP authorities’ move to ban commercial banks from selling deposit products on third-party platforms in January 2021.

When times were good, the rural banks and the “criminal gangs” behind their operations were able to secure sufficient funds to sustain their scheme. But as the Chinese economy swiftly deteriorated as a result of a real estate sector debt crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, Beijing’s draconian “zero-COVID” policy, and global economic decline, those banks struggled to recover loans from developers and pay interest to its depositors. That, plus possible schemes by the “criminal gangs” to siphon off funds, would have quickly exposed the four rural Henan banks’ financial risks, forcing them to freeze deposit accounts mid-April.

China’s worsening economic conditions also appear to be a key factor in the Bank of Nanjing’s debt crisis. The industry analyst’s June 30 WeChat postings and information from mainland media indicate that debt problems at the Nanjing local government and property developers like China Evergrande have led to a surge in non-performing loans at the Bank of Nanjing, triggering the bank’s implicit risks.

Tip of the iceberg

The Bank of Nanjing case and trouble with the four Henan banks are likely just the tip of the iceberg of serious systemic and financial risks with small- and medium-sized banks in China. Other banks could soon report similar problems as the financial contagion from the property sector debt crisis spreads and the Chinese economy moves towards recession.

The CCP authorities are wary that public anger from the banking crisis could get out of hand and have moved quickly to address the issue, with local authorities in Henan having thus far resorted to both carrots and sticks. On the one hand, the authorities mobilized security forces to disperse those outside the Zhengzhou PBoC on July 10. On the other hand, the authorities moved the next day to denounce the “criminal gang” behind the bank fraud the next day and announce advance payments to persons or institutions with 50,000 yuan or less in deposits from July 15.

The Xi leadership has pressing reasons to resolve the banking trouble promptly. Letting the issue drag out would undermine public confidence in small- and medium-sized banks across the country, triggering more bank runs and a full-blown financial crisis. Xi’s factional rivals in the CCP elite would also look to exploit the crisis to undermine the Xi leadership before the 20th Party Congress and attempt to block Xi Jinping’s bid to extend his tenure as Party leader. Escalating factional struggle and financial crisis would in turn erode the CCP’s political legitimacy and seriously threaten regime security.