◎ The following analysis was first published in the April 8, 2021 edition of our subscriber-only SinoWeekly Plus newsletter. Subscribe to SinoInsider to view past analyses in our newsletter archive.

On April 6, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region government held a special press conference in Urumqi to discuss “Xinjiang-related issues.” During the conference, Xinjiang High Court vice president Wang Langtao announced that two former Xinjiang officials, Sattar Sawut and Shirzat Bawudun, have been sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve. Both officials recently featured in “War in the Shadows,” a propaganda documentary about “extremism” and “two-faced” officials in Xinjiang that aired on state television on April 2, and made statements that appeared to be forced confessions. Shirzat Bawudun, the former Xinjiang Political and Legal Affairs Commission deputy director, was charged with taking bribes and conspiring with a “terrorist organization.” Meanwhile, former Xinjiang education department head Sattar Sawut was charged with separatism and taking bribes.

According to the “War in the Shadows” documentary, Sawut, his former deputy Alimjan Memtimin, former Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences vice president Abdurazaq Sayim, and former government publishing house chief editor Tahir Nasir were guilty of writing and publishing “problematic” Uyghur-language elementary and middle school textbooks. In 2016, the Xinjiang provincial government deemed that the textbooks, which reportedly influenced 2.32 million school children and tens of thousands of educators over 13 years, contained material promoting “ethnic separatism, violent terrorism, and religious extremism.” The Xinjiang High Court later ruled that the textbooks incited Uyghurs to carry out violent attacks in Urumqi in 2009 (“July 5 Incident”) and 2014 (“April 3o Incident”), as well as inspire people to become “backbone” members of a “seperatist criminal organization” supposedly headed by the Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti. Tohti is one of the first prominent Uyghurs to be targeted by the CCP in its modern-day persecution campaign in Xinjiang, which started in 2009 and escalated under Xi Jinping.

OUR TAKE

1. The CCP’s evidence for handing out life sentences to Sattar Sawut, Shirzat Bawudun, and the others mentioned in the “War in the Shadows” documentary is thin and dubious at best. The Party once publicly hailed Bawudun as a “counter-terrorism hero,” and he enjoyed a solid career in the regime’s political and legal affairs apparatus before his downfall in 2018. Scholars also point out that the two examples of “ethnic hate” in the textbook produced under Sawut’s “instructions” are either outright lies or exaggerate the trivial.

Meanwhile, the purged Uyghur officials were very unlikely to have been heavily punished for taking bribes. Corruption is endemic in the CCP officialdom, and virtually all officials are liable to be arrested on bribery charges, real or imagined, at a moment’s notice.

The fact that the Party is focusing on its accusation that the Uyghur officials are “two-faced people,” or “liang mian ren” (兩面人), indicates that they are chiefly being punished for political crimes. Further, the charges of “extremism” and “separatism” suggest that the officials are being targeted as part of the CCP’s persecution campaign against the Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

2. Shirzat Bawudun, Sattar Sawut, and the other Uyghur officials mentioned in the “War in the Shadows” documentary and the Xinjiang High Court’s press conference are being subjected to a Kafkaesque “show trial,” or in American parlance, extreme “cancel culture.” The high-profile punishing of high-ranking ethnic minority officials in Xinjiang for the slightest “infraction”—publishing previously Party-approved education material—sends a chilling message to the Uyghur population that there are no sacred cows in the CCP’s persecution campaign. Moreover, targeting education officials and publishers for Uyghur-language textbooks appears to be part of the Party’s ongoing effort to eradicate the Uyghur language and culture.

The CCP’s actions in Xinjiang have been correctly described by many scholars and observers as cultural genocide. Those familiar with the Party’s many political and persecution campaigns will further recognize that the Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang are but the latest victims of the CCP’s permanent, ideological driven effort to control society in an endless quest to survive and dominate. Marxism-Leninism is an atheistic, totalitarian ideology, and the CCP runs a gangster regime that promotes a culture of struggle, deception, and corruption. The Party only feels “safe” when the bulk of society embraces and expresses complete loyalty to its malign culture and quasi-religious ideology. Those who instead adhere to the universal values (morality, liberty, freedom, etc.) found in most traditional cultures, or who practice religion represent the greatest threat to the CCP because the Party cannot survive long in an environment that works against its aberrant ideological underpinning. To advance the “CCP-ification” of society, the Party has launched campaign after campaign since the inception of the PRC to root out religion and traditional culture in China.

To dominate the Han Chinese, the CCP has been systematically eradicating traditional Chinese culture and language through compulsory mass indoctrination in Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, the introduction of simplified Chinese script and promotion of CCP-influenced Mandarin over other dialects, the persecution of intellectuals (Anti-Rightist Campaign and nonstop arrest of scholars even in the modern era), and the outright destruction of cultural artefacts and buildings (Cultural Revolution). Meanwhile, and especially in recent decades, the CCP has appropriated and re-interpreted select aspects of traditional Chinese culture (the image of Confucius and ancient strategic treaties) to enhance its control of society at home and further its hegemonic ambitions abroad. Religion must either come under the Party’s control (state-approved churches, temples, etc.) or be stamped out (house Christians, Falun Gong, etc.)

In dominating ethnic minorities, the CCP uses all the aforementioned methods plus policies of and appeal to “Hanification” and “nationalism.” Beijing will accuse the Tibetans and Uyghurs of being “separatists” to justify enhanced “stability maintenance” measures in Xinjiang and Tibet, all in the name of preserving regime security. Meanwhile, the Party’s “Hanification” of Xinjiang, Tibet, and other ethnic minority regions is really a more invasive and obvious form of “CCP-fication”—Han Chinese are migrated to those regions to change the population composition and lifestyle (e.g. nomadic to agrarian society); efforts are made to eradicate traditional indigenous culture and language; and ethnic minorities are encouraged to adopt Party-approved “moderate” forms of their local religion, which are modified to accommodate and prioritize “socialist core values.”

Today, the international community is finding its voice on the CCP’s persecution campaign in Xinjiang. Governments are recognizing that the horrors of mass incarceration, torture, rape, and slave labor count as genocide and crimes against humanity. Multinational corporations are starting to boycott Xinjiang cotton, while nonprofits are calling for a boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in China. Still, the international community needs to do one better and directly call out the CCP. The atrocities in Xinjiang are the culmination of the Party’s many political and persecution campaigns, and Communist China dares to brazenly commit gross human rights abuses because the world largely condoned earlier abuses. For example, unsustained international sanctions against the PRC over the Tiananmen Square Massacre emboldened the CCP to go after Falun Gong in 1999, and the lack of international condemnation over Falun Gong likely led the Party to believe that it will again get away with targeting Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Also, the lack of international outcry over the CCP’s most egregious persecution methods like forced organ harvesting has resulted in the expansion of their use—the Party experimented with forced organ harvesting on Uyghurs in the 1990s, rolled it out on a “significant scale” against Falun Gong practitioners and other prisoners of conscience in the 2000s, and has likely come full circle in targeting incarcerated Uyghurs in Xinjiang today, according to David Matas, a Canadian human rights lawyer who was one of the first to spotlight the CCP’s forced organ harvesting.

In the previous issue of this newsletter, we noted that the Shanghai municipal government started piloting on April 1 so-called “service and management” population regulations where people visiting the city are required to submit their personal details to the local authorities within 24 hours of arrival. This sort of surveillance control is akin to the more intense form of checkpoint system currently in place in Xinjiang. Given the CCP’s history and nature, the “Xinjiang-ization” of the rest of China is only a matter of time. This process, however, can be slowed and even reversed if the international community keeps calling out the Party and demands accountability. Businesses, investors, and governments who do not want to be accomplices to a genocidal regime can also do more to raise awareness about Xinjiang and other human rights abuses in China.

3. The political dimension of the purge of Shirzat Bawudun, Sattar Sawut, and other Uyghur officials can quickly disappear amid the backdrop of the CCP’s cultural genocide in Xinjiang. However, the main charge against them (“two-faced people”), the political backgrounds of the officials, and anti-corruption data indicate that their case very much also concerns Party elite politics and factional struggle.

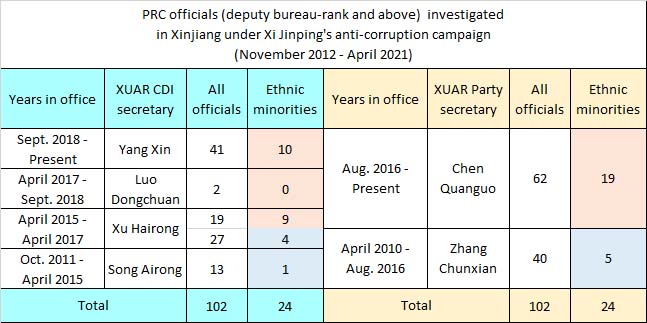

A review of incomplete statistics compiled from publicly available CCP official sources (see Table 1) suggests that the recent punishing of Uyghur officials is both political rectification of the Xinjiang officialdom and persecution of ethnic minorities. Since Chen Quanguo took over as Party secretary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in 2016, 19 ethnic minority officials at the deputy bureau-level and above in Xinjiang were purged, up 280 percent from the five under Chen’s predecessor Zhang Chunxian. However, Chen also purged 55 percent more officials of all ethnicities at the deputy bureau-level and above as compared to Zhang (62 to 40).

The political rectification aspect becomes clearer in examining the number of officials purged under the four discipline inspection chiefs who served under Zhang Chunxian and Chen Quanguo. Investigations clearly stepped up under Xu Hairong (46), who took over from Song Airong during a time when factional struggle between the Xi Jinping camp and the Jiang Zemin faction was heating up in 2015. The appointment of Luo Dongchuan in 2017 only led to two investigations, which probably explains why he was replaced about a year-and-a-half later by Yang Xin, who promptly ramped up arrests (41).

The political backgrounds of the recently punished Xinjiang officials offer a clue as to why they might be chosen. As we examined in the previous newsletter, Shirzat Bawudun is a possible Jiang faction associate or member, given his rapid rise in the Xinjiang political and legal affairs apparatus during a period where the promotion of “stability maintenance” officials largely hinged on them either winning the trust of Jiang faction (many Jiang faction officials held senior positions in the political and legal affairs apparatus in the 2000s and during most of Xi’s first term), or their active participation in the Falun Gong persecution campaign (sometimes the two factors overlap). Bawudun’s career also took off under Jiang faction members Wang Lequan and Zhang Chunxian, and saw his downfall under Xi loyalist Chen Quanguo.

The factional alignment of Sattar Sawut, Alimjan Memtimin, Abdurazaq Sayim, and Tahir Nasir is less clear. Their involvement in education and publishing work means that they belong to a subset of the CCP’s propaganda apparatus, another regime organ prized and controlled by the Jiang faction during its period of dominance in the regime (1997 to 2012). All four Uyghur officials also saw career progression at varying paces under Jiang faction Xinjiang Party bosses Wang Lequan and Zhang Chunxian. Those two points, however, may be enough for the Xi camp to consider them Jiang faction supporters and designate them as “two-faced people.”

“Two-faced people” is the modern, less sensationalistic way for Beijing to indicate that the labeled officials have suspect loyalties or belong to rival factions. During the Mao era, today’s “two-faced people” would have been branded “counter-revolutionaries,” “capitalist roaders,” or members of “anti-Party cliques” (反黨集團). Under Xi Jinping, one of the earliest prominent uses of the term “two-faced” came in the PLA Daily’s criticism of disgraced Central Military Commission vice chair and Jiang faction member Xu Caihou. Xi also called for “resolutely opposing two-faced factions and two-faced people” (堅決反對搞兩面派、做兩面人) in his 19th Party Congress report in Oct. 2017; notably, Jiang faction associates Sun Zhengcai and Fang Fenghui were purged in the lead up to the key political conclave. In January 2018, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection echoed Xi’s opposition of “two-faced factions and two-faced people,” further popularizing the use of the “two-faced” label.

“Two-faced people” takes on at least two layers of meaning when used in context of the recently purged Uyghur officials. First, they are accused of harboring dual loyalties to the Party and the regime by supposedly embracing ethnic and religious “extremism” and “separatism.” Second, they are accused of having dual factional loyalties instead of being fully behind “Party Central with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core.” CCP officials, who are steeped in Party culture and are sensitive to matters concerning their political survival and career progression, would prioritize the second layer over the first in consolidating “lessons learned” from the Uyghur officials case. Even more discerning officials could infer that the factional struggle in the CCP elite must still be quite fierce if the authorities are still harping on “two-faced people” despite an anti-corruption campaign nearing the end of its first decade. And officials who know about the Xi-Jiang struggle through direct participation or by consuming banned political literature (foreign newspapers, magazines, and websites) without getting caught may be inclined to inaction (不作爲) or rebellious opportunism in the lead up to the 20th Party Congress in 2022; after all, a Feb. 16 Wall Street Journal article covering the political aspect of Ant Group’s scuppered IPO notes that Jiang Zemin “remains a force behind the scenes” even though “[m]any of Mr. Jiang’s allies have been purged in Mr. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.”

4. The punishing of Uyghur education and publishing officials over extremely minor issues like “problematic” textbooks also spotlights a crucial structural weakness in the CCP’s authoritarian system and political culture. As we have repeatedly noted, CCP officials who are preoccupied with career security and progression will usually “prefer left rather than right” (寧左勿右) in executing most policies because measures that are “left” tend to be the more politically correct ones in the regime. While Beijing might not agree with the more “left” implementation of policies, it lacks standing to take mis-performing officials to task on policy issues per the regime’s own political norms (Beijing may later remove those officials on anti-corruption charges). Sometimes, policy miscues are covered up by the sheer sweep of events and bureaucracy. Increasingly, however, the “prefer left rather than right” method of policy implementation is backfiring on Beijing, with “wolf warrior” diplomacy and heightened international pressure against the regime being a prominent example. The CCP’s extremely unreasonable “literary inquisition” (文字獄) against Uyghur officials will likely contribute to greater international pushback against the PRC.

The “War in the Shadows” documentary and the punishing of Sattar Sawut and others involved in the publication of Uyghur-language textbooks are classic examples of CCP officials blowing trivialities out of proportion to serve political purposes, a kind of criticism known as “shang gang shang xian” (上綱上線). It was very common for officials in the Mao era who “prefer left rather than right” to “shang gang shang xian” to score political points or survive being targeted. In fact, Xi’s father Xi Zhongxun was the victim of a high-profile “literary inquisition” case in the lead up to the Cultural Revolution. The elder Xi reviewed and was mentioned in an autobiography of the CCP martyr Liu Zhidan published in 1962. Subsequently, Mao’s brutal spy chief Kang Sheng criticized the book as a piece of “anti-Party” work because it alluded to purged ex-CCP regional boss Gao Gang. Xi Zhongxun and some others mentioned in the book were later designated members of an “anti-Party clique,” the forerunner of “two-faced people,” and purged. Those involved in the Liu Zhidan book case were only fully “rehabilitated” from what the Party described as “an extensive, modern literary inquisition” in 1979.