◎ An unusually large number of influenza cases reported in the winter of 2019 and 2020 coincides with the appearance of the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen in central China, possibly masking a coronavirus epidemic far more severe than suggested by official data.

A Harvard Medical School study published in early June 2020 suggested that the Wuhan coronavirus may have been spreading in China as early as last August. Researchers observed that satellite images at the time showed unusual concentrations of traffic around hospitals, as well as increased searches for infectious disease-related keywords on Chinese search engine Baidu.

The study has not yet been peer-reviewed and does not draw upon other evidence. The authors also noted that there is no conclusive link between the material they cited and the possible spread of COVID-19 in late summer 2019 (the earliest cases admitted to by the Chinese authorities were detected in December). However, in the context of other reports and available data, the Harvard study lends weight to theories that the outbreak had already begun months before authorities had identified the pathogen.

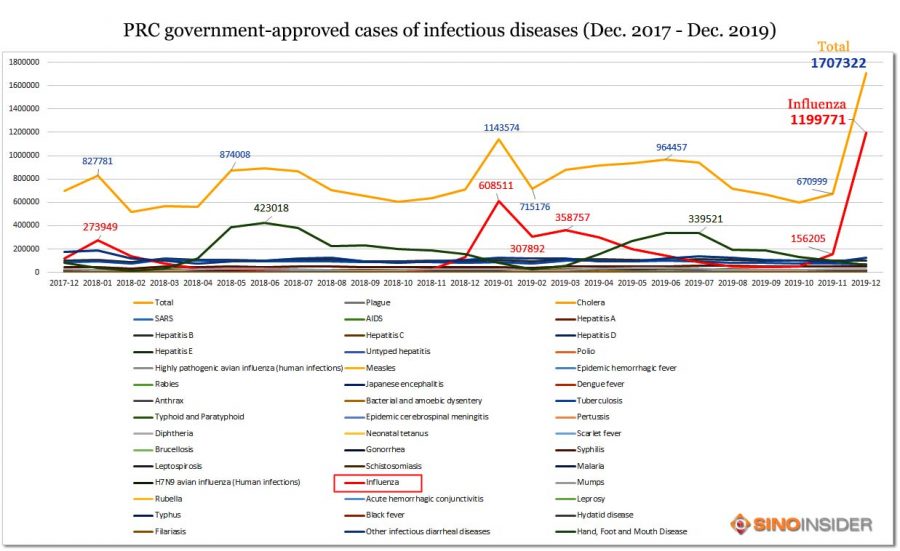

An examination of official Chinese data shows a spike in the flu cases in mainland China in late 2019:

1. The People’s Republic of China reported unusually high numbers of influenza cases during the winter of 2019-2020.

According to the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), in December 2019, the number of flu cases had jumped to 1,199,771, nearly twice the 608,511 people who got the flu that January, China’s peak for the last winter. The month-on-month increase from November 2019 was 768 percent, compared with January’s 467-percent increase from December 2018, when there were 130,442 cases recorded.

Similar to the previous year, October 2019 saw 1.1 times more flu cases than the previous month. But November 2019 saw the number of cases triple from October compared with 2018’s 1.82-factor increase between October and November. This discrepancy became even more pronounced in December 2019, when flu cases exceeded the November number by 7.68 times.

Flu cases in China typically peak in January. For instance, there were 273,939 flu cases in January 2018 and 120,800 cases in December 2017, that winter’s peak. The month-on-month increase was 227 percent. There were 608,511 flu cases in January 2019 and 130,442 cases in December 2018, that winter’s peak. The month-on-month increase was 466 percent. By comparison, the month-on-month increase in November 2019 and December 2019 was 768 percent—an atypical phenomenon.

By the time of writing, flu statistics for the second half of 2019 (starting July) are no longer available on the China CDC website.

2. We also found discrepancies in perusing weekly statistics released by the China National Influenza Center.

On Dec. 27, 2019, the Influenza Center released its report for the week of Dec. 16-Dec. 22. After this, the weekly flu statistics reports stopped. And beginning in the fourth week of 2020, no more flu outbreaks (10 or more cases in the same community or work unit) were registered.

Our take

Based on the timing of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak, we have reason to believe that the uncharacteristic explosion of flu cases in December may be due to the undetected spread of the coronavirus. In reviewing Chinese flu statistics, papers released by Chinese and international health experts, and official PRC statements, we estimate that tens of thousands of people could have been infected with COVID-19 by the end of December.

In Jan. 20, 2020, the PRC acknowledged that the novel coronavirus was contagious among humans, after weeks of downplaying the seriousness of the outbreak that started in Wuhan in late 2019. By the end of January, the Wuhan virus had spread to all parts of China, and cases were being reported in multiple countries.

While the novel coronavirus pandemic has spread to almost every country on earth, official figures recently published by the PRC authorities show very few new cases and deaths, creating the impression that the Chinese Communist Party has successfully put the brakes on the crisis. However, the CCP’s propensity for active deception makes it necessary to view these claims with great skepticism.

1. There are multiple indications that the novel coronavirus outbreak began in November 2019 or even earlier, and not in December as initially claimed by the CCP regime.

On Feb. 26, 2020, mainland Chinese media outlet Caixin reported on a paper called “Analysis of mutation and evolution in the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2,” released by the Biosafety-Level-3 (P3) laboratory at the Southern Medical University in Guangzhou. According to the paper, the novel coronavirus made its first appearance as early as Sept. 23, 2019.

On March 13, the South China Morning Post reported on an internal PRC government document containing details about the early spread of the Wuhan coronavirus.

The internal document revealed that a 55-year-old Wuhan resident had contracted the disease by Nov. 17, 2019, becoming the earliest known case so far. From that date, there were new cases reported nearly every day. By Dec. 15, 27 people had been confirmed infected. Dec. 17 saw the first double-digit increase; by Dec. 20, the number of confirmed cases had reached 60.

2. In our 2020 CCP factional struggle report, we wrote that the “unusually large number of influenza cases in November 2019 has led some observers to suspect that the Wuhan coronavirus was already beginning to spread that month. The sharp rise in the stock value of a biopharma company that would go on to work with a PRC government research institute to produce the first COVID-19 vaccine that was approved for clinical trials is also suspicious.”

The company, CanSino Biologics, saw its stock value more than double from what it was in August.

3. The CCP prevented doctors and researchers from investigating the virus in the early stages of the known outbreak. In addition, the Party has been extremely opaque about the circumstances concerning the emergence of the virus, while rolling out draconian measures to contain its spread. Later, the regime even pinned blame for the virus on foreign countries, including the United States.

Deception, draconian epidemic control, and disinformation campaigns are characteristic of the CCP regime. The Party has even more reason to engage in cover-up if it had discovered that the virus was spreading well before it was detected.