◎ The fresh social tensions in Leiyang are the result of local government-business corruption and dwindling government coffers.

Mass protests over problems in the education system recently broke out in Leiyang, a city in the south-central Chinese province of Hunan. Earlier this year, we covered an incident where the Leiyang government delayed wage payments to civil servants owing to a lack of funds. Then, civil servants unfurled banners in the streets to protest the delay in receiving their salaries.

The fresh social tensions in Leiyang are the result of local government-business corruption and dwindling government coffers.

The backdrop:

1. In May 2018, the Leiyang government issued an order to restrict public school class sizes to a maximum of 66 students per national requirement. Parents in Leiyang told media outlets that while classes have been oversubscribed for at least a decade, the local government has never embarked on school expansion projects to resolve the issue.

To meet the national class size requirement, the Leiyang government has to add classes to accommodate 10,700 students. However, the government announced that it would transfer all fifth and sixth graders (over 9,000 students) to a private boarding school, which implies a shortage of government funding.

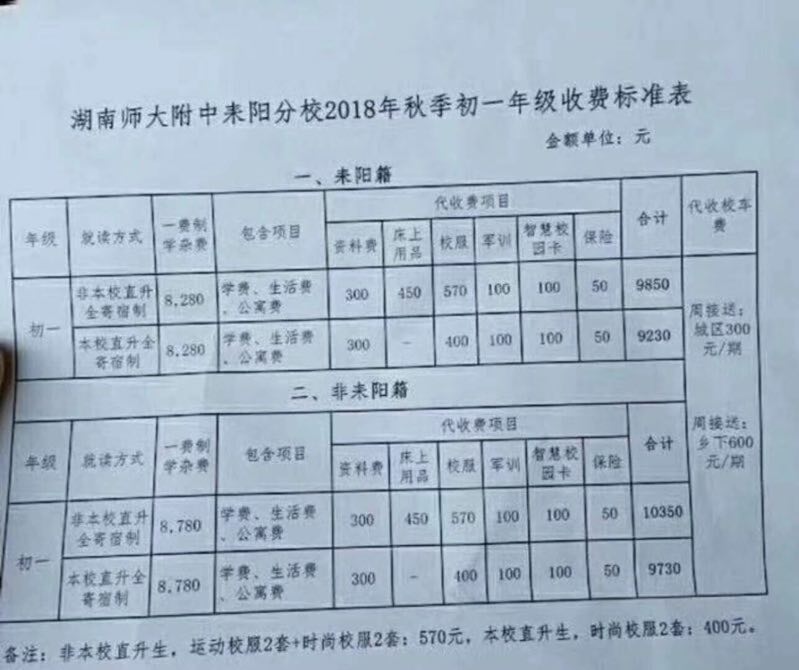

Parents of the affected students have voiced many grievances about the forced transfer. They note that that the private school is located in an inconvenient location and their children would have to reside in dormitories—some unfinished and with smells of formaldehyde permeating the air—during the week. The parents also believe there would be a shortage of teachers and the charging of extra fees at the private school despite official assurances; some parents noted that private schools fees (including supplementary costs) are 10 times that of public schools. Another worry is that the transferred students would have difficulty gaining entry into the junior high school that is affiliated with the public elementary school.

2. On Aug. 31, several parents who approached the Leiyang government to complain about the mandated school transfer were detained, a local resident told The Wall Street Journal.

On Sept. 1, over a thousand parents assembled at six public schools before marching with banners to the Leiyang government offices. After government officials refused to meet with them, the parents blocked a highway in protest. Police arrested dozens of parents.

In the evening of Sept. 1, thousands of parents gathered to protest outside the local Public Security Bureau compound. The situation grew tense at about 1:00 a.m., and the police used force to clear the area. Some parents were wounded, and over 40 people were arrested.

On Sept. 2, large numbers of Leiyang residents took to the streets in protest. Meanwhile, hundreds of parents continued to assemble outside the police compound. By the evening, the parents were yelling for the public security bureau chief to step down.

After social tensions bubbled over, the government dispatched thousands of SWAT police into Leiyang and tightly controlled online speech. Online messages containing the characters “Leiyang” were censored.

3. The private school where a majority of students were to be transferred to is the Leiyang branch of a high school affiliated with Hunan Normal University. The government order would see the high school open classes for fifth and sixth graders

According to publicly available information, the private school is a full-time boarding school that was established in September 2014 as a joint venture between the Leiyang government, the Hunan Lufang Group, and Hunan Normal University’s affiliated high school. The high school’s website does not list the Leiyang branch, but notes that Hunan Lufang had plans to invest 480 million yuan (about $70.3 million) for the school’s construction works.

According to accounts from parents in Leiyang, the fees for a semester in the first year of middle school in the private school costs around 10,000 yuan. Moreover, the school charges a 7,000 yuan intake fee for a fifth grader. Parents say that such astronomical fees (the average citizen’s monthly income in Leiyang is only about 2,000 yuan) go against what the local government promised earlier about charging public school fees at the private school.

Based on our study of official information, Chinese language media, and social comments, the Leiyang government had colluded with Hunan Lufang when seeking tenders to build the Leiyang branch of the high school affiliated with Hunan Normal University. Also, Li Zeyuan, the chairman of Hunan Lufang, was formerly in the leadership ranks of Leiyang City Party Committee’s 610 Office, an extrajudicial security organ that chiefly coordinates the persecution of Falun Gong. While in domestic security, Li earned the nickname “Leiyang’s Number One Mafia Boss” because he was found of suppressing local residents. In Aug. 2010, Li ran afoul of Hengyang City’s anti-corruption body when he was found to have funded an official who was being blackmailed over pornographic videos.

4. The Leiyang government’s financial woes were exposed in June after Leiyang civil servants complained that payment of their wages had been delayed. The government’s self-sufficiency rate has been falling year after year, reaching only 25.19 percent in 2017. On July 27 this year, the ratings of an investment bond issued by a town in Leiyang was adjusted to junk status.

The big picture:

The Sino-U.S. trade dispute has aggravated the worsening of China’s economy. The Trump administration has already imposed 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion of Chinese goods, and is looking to levy an additional $200 billion worth of Chinese products on Sept. 6.

Chinese officials and scholars have been projecting “economic stability” and releasing data that show an increase in government revenue. However, signs that local governments are seeing funding shortage have kept surfacing, and the situation seems to be getting more severe.

Our take:

1. In our June 13 article on Leiyang’s financial woes, we wrote: “We believe that local governments in China would find it more and more difficult to pay civil servant wages, and the CCP would find it increasingly difficult to exert control over Chinese society.”

The recent protests in Leiyang affirm our analysis.

2. Leiyang City is a county-level city in Hunan. It has the largest urban area and population in the province. Leiyang is also one of the top coal-producing regions in China and its GDP has long ranked in Hunan’s top five. Yet the city has been revealed recently to be in financial difficulty, and its financial woes have now triggered mass social unrest.

According to a June report by Caixin.com, the Leiyang government’s financial revenue, particularly non-tax revenue, has been substantially high for several years. “Into the left pocket, out from the right pocket,” Caixin noted, implying fraudulent income and expenditure by the Leiyang government. In recent years, China’s finance ministry has been auditing local government revenue streams, including non-tax revenue, as well as the discrepancies in financial and economic figures following provincial leadership change. Given stricter controls by the central government, Leiyang’s non-tax revenue for 2017 can be expected to fall sharply.

3. As stated in the previous point, Leiyang has one of the highest GDPs in Hunan Province. If the Leiyang government is having financial problems, then there is a good chance that the local government in other parts of China are in similar or worse financial situation. The mass social unrest in Leiyang, which was sparked by the local government’s financial woes, foreshadows the outbreak of turmoil elsewhere in the country.

4. Given that the Leiyang branch of the high school affiliated with Hunan Normal University is a venture backed by government-business collusion, Leiyang residents are understandably concerned about corruption and conflict of interest. The colluders stand to make vast sums from the student transfer—presuming 8,000 students (about 80 percent) have no choice but to attend private school and pay 8,000 yuan per person for a semester, the school would collect tuition fees totaling 64 million yuan.

5. On the one hand, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) government seems to be running short on funds, and cannot meet the demand for public services brought about by increased urbanization.

On the other hand, the CCP is spending lavish sums on foreigners. On Sept. 3, Xi Jinping pledged $60 billion in aids and loans to Africa. Meanwhile, international students in China are entitled to subsidies worth 50,000 to 90,000 yuan annually as part of a CCP drive to attract students to Chinese universities. Local students receive significantly less financial subsidies.

6. Sino-U.S. trade tensions have directly or indirectly resulted in the exposure of government fraud in China. For instance, local governments have admitted to faking GDP data; the statistics bureau changed statistical methodology and sample size to produce healthier-looking financial data; and in the Leiyang case, government-business collusion is bubbling to the surface.