◎ The Trump administration has been meeting China’s challenge on a number of fronts.

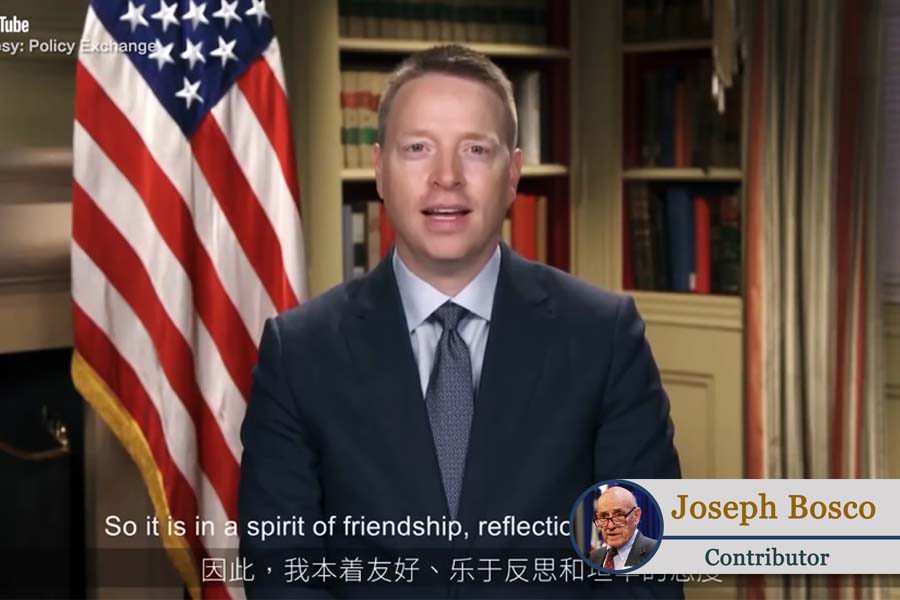

For the second time in six months, President Trump’s deputy national security adviser, Matt Pottinger, has delivered a major speech on China in fluent Mandarin. Both talks targeted the Chinese people to the extent the message made it over Communist China’s Great Firewall. (In Mandarin, he also congratulated the people of Taiwan in May on their seventh successful democratic election.)

More significantly, Pottinger’s message continued in the ground-shaking tone of accusation and call for reform established by Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, along with a series of major addresses by Defense Secretary Marc Esper, national security adviser Robert O’Brien, and other administration officials.

While Pottinger’s talks stand out because of his linguistic facility in Chinese, his powerful appeal for candor and reciprocity is consistent with the values-driven messages from the entire Trump administration. What is emerging is the beginning of an all-out ideological campaign worthy of “Cold War II.” Many who never liked the original ideological confrontation resist the idea of a new era of frosty great-power relations.

But if managed wisely and with discipline, this one can end as relatively peacefully and successfully as the first global contest of ideas. For the West to prevail, America and like-minded nations need to sustain it over the long term. The Trump team that is already waging defensive information warfare against China is more likely to do so than political rivals, who would have to reverse a collective mindset shaped by decades of failed engagement policies.

Given the deep-seated hostility of China’s communist ideology, the strategic information campaign could and should have been launched at any point over the past 40 years. Richard Nixon premised his opening to China on the conviction that it posed the greatest danger to world peace, saying that “China must change.”

But Henry Kissinger was left as the quasi-official steward of China accommodation over the ensuing decades, simultaneously advising both Chinese and American leaders, and inspiring generations of revolving-door officials and academics who dutifully followed his style of amoral “realism.” Until Trump, none of Nixon’s successors seriously pressed change on the communist regime or monitored its supposed progress toward integration with the civilized world.

The Trump administration, by contrast, has been meeting China’s challenge on a number of fronts: unfair and deceptive trade practices; intellectual property theft and cyber-espionage; threats to maritime security in the South and East China Seas; subversion of international economic sanctions against North Korea; erosion of Taiwan’s security and international democratic identity; massive human rights violations in Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and against religious and spiritual groups and political dissidents. Beijing’s deceptive, reckless and possibly deliberate unleashing of the Wuhan-origin coronavirus has brought the China problem into the daily consciousness of people around the world.

The recent series of speeches and writings by administration officials has taken the indictment of the communist regime to a new level. More precisely, it has returned the discussion of China’s existential challenge back to its fundamentals, when Nixon described the ruling party as so steeped in anti-Western animosity that it remained ideologically predisposed “to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors.” That was the China Nixon was determined to change.

Instead, China’s leaders masterfully played a devious geopolitical shell game. Credulous Western officials, profit-driven corporate leaders, and ambitious Western scholars were convinced — or say they were — that Beijing shared their reform aspirations for China, North Korea’s denuclearization, global non-proliferation, and concern about climate change.

The solution, according to Trump administration officials, must be to return seriously to the change-China agenda — but this time by taking concrete measures to support the actors who ultimately must press the communist leaders to reform: the Chinese people themselves.

In his July speech at the Nixon Library, Secretary Pompeo put it this way: “We must … engage and empower the Chinese people — a dynamic, freedom-loving people who are completely distinct from the Chinese Communist Party. … The CCP fears the Chinese people’s honest opinions more than any foe.”

Without using the term, Pompeo invoked the West’s victorious experience with the Cold War: “Changing the CCP’s behavior cannot be the mission of the Chinese people alone. Free nations have to work to defend freedom.”

Meeting the challenge the secretary laid out is a formidable task, given the half-century head start China’s communist system has been given to entrench, enrich and empower itself. But Pompeo expressed his “faith we can do it … because we’ve done it before. We know how this goes.”

He noted the weakness at the core of the Chinese communist dictatorship that compels it to repeat the errors of earlier tyrannies: “[T]he CCP is repeating some of the same mistakes the Soviet Union made — alienating potential allies, breaking trust at home and abroad, rejecting property rights and predictable rule of law.”

China’s poisoned gift to the world — the coronavirus pandemic — is furthering the deterioration of its international standing by exposing the inhuman nature of the regime. It has reminded Western countries tempted by the allure of economic benefits — if they would only close their eyes and seal their lips — of why they are part of the West.

Even European critics of President Trump’s rhetorical style and negotiating gambits have come to recognize their effectiveness in meeting the challenges from both Russia and China. Earlier, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg credited Trump’s tough message with increasing member countries’ contributions to the defense against Russian aggression.

More recently, European countries are returning to their moral and political roots as they recognize the need for the United States to lead the way in confronting China, and for them to join in the existential struggle. Friedolin Strack of the Asia-Pacific Committee of German Business this week applauded Washington’s attention to the human rights violations in Xinjiang. And he noted that U.S. pressure on China in Trump’s trade negotiations extracted preliminary Chinese reforms that provided secondary benefits to the European Union. He welcomed greater U.S.-Europe cooperation in confronting China’s economic and moral challenge.

As has been said, “America First” does not mean America alone — and China is reminding the West of why it needs to remain united.

Joseph Bosco served as China country director for the Secretary of Defense from 2005 to 2006 and as Asia-Pacific director of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief from 2009 to 2010. He is a nonresident fellow at the Institute for Corean-American Studies and the Institute for Taiwan-American Studies, and has held nonresident appointments in the Asia-Pacific program at the Atlantic Council and the Southeast Asia program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of SinoInsider.