◎ There long have been more than sufficient moral and security reasons to press for major political reform in China.

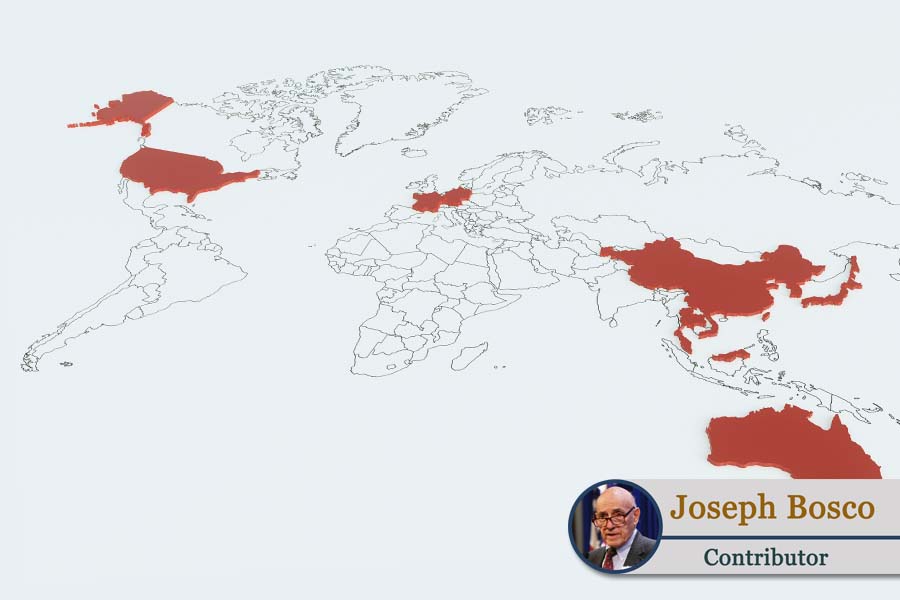

China’s coronavirus, after wreaking vast human suffering and a mounting death toll in Wuhan Province and elsewhere in China, has spread to other countries, disrupting travel and commerce and spurring well-founded fears of a global pandemic.

It is hard to imagine that anything good could come out of this public health disaster. Yet, if the international community can muster the vision and courage, coordinated national policies could make it a historically transformative event. Since the totalitarian incompetence and callous dishonesty of the Chinese Communist Party brought about the public health catastrophe, it would be the ultimate justice if it proved to be the cause of its political demise. Western governments can make it happen.

There long have been more than sufficient moral and security reasons to press for major political reform in China. After all, that was the original motivating principle underlying Richard Nixon’s opening to China in 1972. He had written in his campaign that “The world cannot be safe until China changes.” He said it could not be left isolated to “nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors.” To drain off Mao Zedong’s “poison,” he warned, “the world must open to China and China must open to the world.”

In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping said “reform is China’s second revolution,” and did undertake some opening up of China’s economy. But hopes that political reform would follow were brutally dispelled by the Tiananmen Square massacre. As for China’s relations with the outside world, Deng cautioned communist colleagues to “hide your capabilities, bide your time.”

In 1995 and 1996, Jiang Zemin added some meaning to Deng’s cryptic admonition by demonstrating that the use of force was still very much in play under Mao’s teaching that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” China fired missiles toward Taiwan to protest its resolute progress to democracy and, when the U.S. moved aircraft carriers to the region, a Chinese military official warned, “You care more about Los Angeles than Taiwan.” A few years later, another Chinese general talked of obliterating “hundreds of American cities.”

By 2000, 30 years after Nixon’s opening was supposed to have started the process of Communist China’s liberalization, Washington once again tried coaxing it into reform. But, perversely, the Clinton administration did so by abandoning the annual human rights review that undergirded Permanent Trade Relations with China.

President Clinton totally disentangled human rights considerations from trade privileges, as if they were unrelated, to allow Communist China into the World Trade Organization. When I testified against China’s admission, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair Jesse Helms asked if its inclusion would finally succeed in “changing China.” I stated my fear that it was more likely to change us.

Once China entered the WTO, predictably, it was given great leeway and available enforcement mechanisms often were ignored. While integration into the world economy was supposed to bring long-anticipated political reform, the West could not even get China to adhere to the trade rules it ostensibly had accepted.

Given that record of Western accommodation, Xi Jinping ascended to power finding it no longer necessary to follow Deng’s hide-and-bide strategy. China openly flaunted its capabilities and laid bare its aggressive intentions in the East China Sea, the South China Sea and, again, toward Taiwan. Beijing also turned the screws on the “one China, two systems” model that was intended to guide Beijing’s dealings with Hong Kong and Taiwan.

As for the conquered peoples of Tibet and East Turkestan/Xinjiang, Xi launched widening crackdowns, culminating in a network of concentration camps where a million or more Uighurs are subjected to gulag-like cruelty and brainwashing.

Within China proper, all religious groups endure deepening oppression. The Falun Gong spiritual movement has been targeted for a special crime against humanity: industrial scale, live organ harvesting that exceeds even the murderous efficiency of the Nazis.

Now with the Wuhan coronavirus, after previous China-centric epidemics — SARS and avian flu — and the opioid crisis, the world should be, quite literally, sick of what the Chinese Communist Party has inflicted in return for its generosity and indulgence.

China’s stubborn exclusion of Taiwan from the World Health Organization is inexcusable and counterproductive, especially given Taiwan’s far superior record of competence and public responsibility.

As for China’s “century of humiliation” at the hands of the West, that debt has been more than repaid. If anything, the Chinese people have reason to resent the new 70 years of shame visited upon them by their own government. From Tiananmen to Hong Kong, thousands of citizen protests each year, and the current revulsion over this latest epidemic outrage, they have demonstrated clearly that it is time for a change.

The West, led by the U.S., should openly state its intention to support internal reform in China. Beijing’s expected charge of interference in China’s domestic affairs, already a routine complaint by now, should be revealed for the hypocrisy it is, given the subversive advantage China takes in its access to Western media and institutions.

The West’s open efforts to encourage political reform in China need be nothing more sophisticated or sinister than an expanded information campaign of radio broadcasting and digital communications. It should inform the population in all Chinese-ruled regions of what is happening elsewhere in the world — including in North Korea, China’s client dictatorship — and in China itself. Armed with the truth, it will be up to the Chinese people to take it from there and determine their fate.

For their welfare, and in the West’s own interests, the effort is long overdue.

Joseph Bosco served as China country director for the Secretary of Defense from 2005 to 2006 and as Asia-Pacific director of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief from 2009 to 2010. He is a nonresident fellow at the Institute for Corean-American Studies and the Institute for Taiwan-American Studies, and has held nonresident appointments in the Asia-Pacific program at the Atlantic Council and the Southeast Asia program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of SinoInsider.