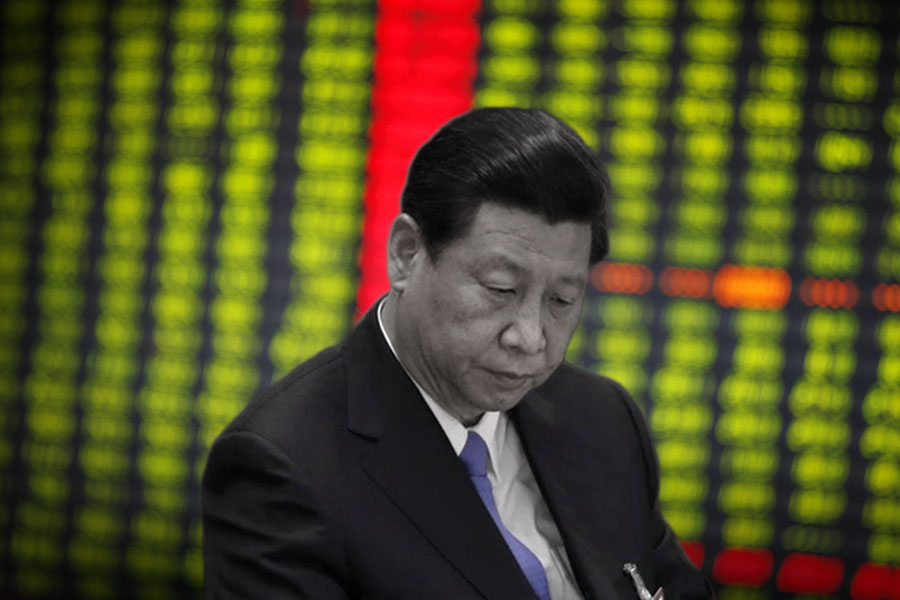

Xi Jinping and the CCP face a dilemma on how to handle the stock market situation.

In late September and early October, Beijing rolled out a series of policies to support China’s flagging economy. The moves, which include measures to boost the capital market, stabilize the property market, and significantly increase debt, saw the A-shares market rally before the National Day of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1.

The rally, however, lost steam after the Golden Week holiday. The Shanghai and Shenzhen indexes closed down on Oct. 8, the first trading day after the markets reopened, and ended lower on the week ending Oct. 11. Meanwhile, the net outflow of main funds from Oct. 8 to Oct. 11 reached nearly 590 billion yuan.

China’s stock market volatility is a sign that investors and observers are not confident in the Chinese economy’s prospects or what Beijing is doing to turn things around. Negative political rumors swirling about Xi Jinping’s recent economic policy shift could also eventually affect market sentiment.

Was Xi pressured to make changes?

Some Chinese observers have argued that Beijing’s seeming embrace of stimulus and other economic support measures indicates that Xi Jinping is abandoning his restrained approach to growth and the economy due to intra-Party pressure.

In searching for evidence that Xi’s grip on power is weakening, those Chinese observers point to the seating of former senior Party officials Li Ruihuan and Wen Jiabao on either side of Xi at the reception dinner for the 75th anniversary of the founding of the PRC on Sept. 30. The observers note that the appearance of Li and Wen at the 2024 reception contrasted with the 2018 reception where there was a collective absence of former senior Party officials, and argue that Party elders had forced Xi to a compromise.

We believe that Xi’s economic policy shift has less to do with intra-Party pressure and compromise, and more to do with pragmatic course-correction to ensure the CCP regime’s survival. CCP leaders have made sudden and drastic policy shifts when faced with severe crises. For instance, Deng Xiaoping promoted “reform and opening up” to spur growth after Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution wrecked the Chinese economy. As for Xi Jinping, he abruptly did away with “zero-COVID” — which was damaging the Chinese economy, impacting people’s livelihoods, and eroding the Party’s political legitimacy — after securing another term and expanding his power at the 20th Party Congress.

The Xi leadership places strong emphasis on security as it strives to ready the CCP regime to face growing geopolitical challenges and deteriorating domestic conditions. To better support its security agenda, the Xi leadership needs steady economic growth and financial stability. This means that Beijing would have to consider rolling out strong stimulus at some point if it wants to power economic growth, prevent the blowing up of local debt and fiscal problems, keep China attractive to foreign investors, prop up the capital market, and avoid the triggering of financial risks.

However, we believe that Beijing’s recent support measures do not resolve the fundamental issues dragging down the Chinese economy even if they do provide some short-term relief to the capital market and real estate sector. Meanwhile, factors such as the renminbi exchange rate, capital outflows, the local debt situation, various financial risks, and bureaucratic inefficiencies will constrain the economic policies and measures that Beijing could later introduce. This means that China’s stock market rally before Golden Week was always hard to sustain despite the buzz that the CCP authorities attempted to create to prop it up.

Rising political risks

Xi Jinping and the CCP face a dilemma on how to handle the stock market situation. On the one hand, letting the market slide would trigger panic and a crash. On the other hand, Beijing is limited in what it can do to support the market.

If Beijing does not introduce fiscal policies that would satisfy investors, many investors could move to cash out from stocks while they still can. Nomura Securities warned in an Oct. 3 note that a market crash after the recent mania could result in rampant capital flight akin to the 2015 market turbulence. The note also warned that worse could follow a busted rally, with Beijing potentially resorting to printing money and the renminbi facing depreciation pressure. A large unwinding of positions by investors would severely undermine market confidence and weaken the public’s faith in Beijing’s ability to rescue the economy.

If Beijing instead gives in to investor expectations and introduces many of the policies being popularly demanded, Xi and the CCP risk eroding their “quan wei” (authority and prestige). Such moves would create the impression that Xi is bowing down to market forces after years of trying to get the better of it. Xi and the CCP could technically get away with the self-undermining of their “quan wei” if the policies meant to placate investors work for a period. But the Xi leadership would be forever behind in resolving fundamental issues holding back the Chinese economy because it cannot easily revert back to derisking and deleveraging without spooking investors. And without deleveraging and derisking, the CCP regime would set itself up for an even greater fall when concentrated risks are eventually triggered. Meanwhile, the failure of popular policies would shred the public’s confidence in the CCP authorities and more quickly trigger economic and financial crises.

Xi Jinping cannot escape accountability from any financial or economic debacle. During the 2015 market turbulence, there was an understanding that Xi was in his first term and did not have everything under control since the financial sector was dominated by “anti-Xi” Party elites. However, Xi cannot easily blame his factional rivals or find other scapegoats for the current economic and financial problems as most of them are the direct consequence of his policies over the past decade, such as “zero-COVID” lockdowns, efforts to strengthen the Party’s control over the economy and financial sector, and the CCP’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy. As China’s stock market volatility persists, Xi and the CCP would find themselves facing ever-mounting political risks.