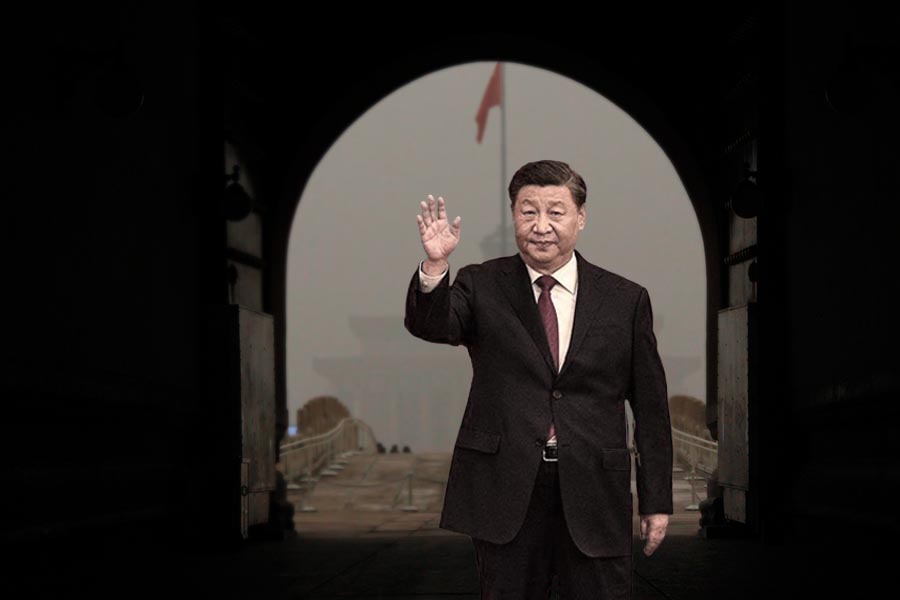

The Chinese Communist Party held its annual meeting of the regime’s rubber-stamp legislature and top political advisory body in the first two weeks of March. By the conclusion of the Two Sessions on March 13, Party general secretary Xi Jinping had secured a third term as president of the People’s Republic of China, confirmed several political allies and loyalists in key positions, and pushed through reforms that essentially subjugated the state government to the Party apparatus.

Xi has long consolidated power with an eye to sidelining factional rivals and improving Beijing’s “governing capacity” so as to better navigate the CCP regime out of crises. Thus far, Xi has had more success in the former endeavor but has seen virtually no breakthroughs in the latter. We believe that Xi’s latest efforts to centralize power will only marginally enhance Beijing’s governance at best, and could even backfire on Xi and the CCP.

Party leads the state

The Party has always sat above the state in the PRC’s system of parallel government. However, clearer divisions were drawn between the Party and the state from the 1980s until as recently as Xi Jinping’s second term in office, partly as a result of Deng Xiaoping’s struggle with factional foes and to professionalize the civil service in the era of market reforms. This meant that the state government had a degree of authority and “autonomy” from the Party to craft and implement policies.

Having a more “professional” state government, however, came with downsides. The CCP’s control over the government was reduced and there was more room for corruption to flourish, including increased official-business collusions and the “gangsterization” of some grassroots organizations. By now firmly establishing the Party’s leadership over the state, Xi is looking to address some of the governing problems that are placing the regime in jeopardy, push through political and economic reforms like those unveiled at the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013, and mitigate the age-old problem of Beijing finding its “orders not leaving Zhongnanhai.”

At the Two Sessions, Xi went about reimposing the “centralized and unified leadership of the CCP and Party Central” over the state government through taking a third term as PRC president, personnel reshuffles, and restructuring the State Council.

In reforming the state government, three new departments were established to advance the regime’s science and technological development, better regulate the financial sector, and oversee the CCP’s construction of a techno-totalitarian society. The reform plan also sought to address problems like financial regulation, food supply, China’s rapidly aging population, and staffing administration. After the Two Sessions, the CCP also announced the creation of five new institutions to strengthen Party Central’s leadership over finance, technology, society, and Hong Kong and Macau affairs, a move that indirectly weakened state control over those areas.

The most notable personnel adjustment that solidified the Party’s leadership over the state was the appointment of Xi’s former secretary in Zhejiang and political ally Li Qiang as premier. Li’s role as a mere “office manager” following Xi’s orders as opposed to the number two leader in the regime with his own ideas was apparent in his first press conference as premier, where he mostly repeated CCP policy talking points without going into the specifics of how he intended to address the myriad problems plaguing the regime.

Meanwhile, the four vice premier slots went to Xi’s allies or loyalists, with the former General Office director Ding Xuexiang serving as the first-rank vice premier. Many of the new State Council ministers are also Xi’s men, with few remaining holdovers from the Jiang-Hu era. The remnant Jiang Zemin faction retained some influence in the top leadership with three of its associates occupying key positions, a development that was likely the outcome of political compromise with the Xi camp. Zhao Leji and Wang Huning were bumped up in standing on the Politburo Standing Committee at the 20th Party Congress and were appointed the new National People’s Congress chairman and chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Consultative Conference respectively. Han Zheng would replace longtime Xi ally Wang Qishan as PRC vice president.

Old wine in new bottles

Xi Jinping’s personnel reshuffles and state institutional reforms are unlikely to help him boost his leadership’s governing ability significantly, if at all.

For one, Xi may have surrounded himself with loyalists and allies, but a key number of them lack experience or qualifications for those roles. For instance, some of Xi’s new vice premiers have never run economic and financial matters at the national level even though they once studied finance or economics. The new premier Li Qiang is also inexperienced in managing the nation’s economy and serving at the national level, having been elevated directly from Shanghai to the central government. The experience deficit in the top leadership could return to haunt Xi at crunch time when actual ability is more important than being loyal to the “centralized and unified leadership” of the Party.

Efforts to streamline bureaucracy and subordinate the State Council to Party Central will also be in vain if officials steeped in Party culture do not abandon their inefficient and counterproductive means of policy implementation. The Xi leadership had already cautioned officials against taking excessive policy steps or resorting to “one-size-fits-all” approaches in carrying out “zero-COVID,” moves that almost certainly led to tragedy in many places as the regime struggled to control the pandemic. Officials placing their personal interests before the Party’s have a tendency to “prefer left rather than right” and go overboard in executing the central government’s orders. In the opposite case, some officials who believe their local case to be hopeless could put up passive resistance (“laying flat,” etc.) to Party Central. Either way, the bad habits of PRC officials threaten to negate any attempt by Beijing to make the government more nimble and effective, which in turn makes it harder for the Xi leadership to rescue the regime from serious crises.

Reinforcing perception

Worse for Xi Jinping, his latest efforts to make the PRC government more efficient so as to preserve the regime and challenge the U.S. at a later time could have the effect of inviting more trouble. The United States and its allies could become more alarmed at what they perceive to be Xi taking concrete actions to circumvent their recent actions to counter the CCP threat, and double down on confrontation with the PRC.

Xi’s Two Sessions moves and statements could also strengthen the view held by the U.S. and its allies that the PRC is dead set on overturning the rules-based international order and persisting in its “revisionist” stances on Taiwan and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Notably, Xi remarked that “Western countries” led by the U.S. have “implemented all-round containment, encirclement, and suppression” against China, while his foreign minister Qin Gang revived the “wolf warrior” in defending the PRC’s foreign policy and echoing Xi’s assessment of America’s strategic posture at a press conference.

All in all, Xi’s moves at the Two Sessions could worsen the various domestic and foreign crises facing the CCP regime instead of alleviating them. Xi could find himself coming under heightened scrutiny and being blamed for all the Party’s ills. As the regime’s space for survival shrinks, Xi could increasingly be compelled to consider his own political legacy.